Busch says the support he gets is "humbling."

Jessica Theobald and her parents left their home in the early morning hours to drive from Pittsburgh to Baltimore to watch as Sid Busch, a man they’d never met, run a marathon.

But it was no ordinary marathon for either Busch or the Theobalds. Busch, a retired Navy senior chief petty officer, has completed hundreds of marathons and half-marathons as a way to honor fallen service members.

“It means so much to me and to our entire family what Sid is doing. He is such an inspiration to us and to so many other families,” said Jessica Theobald said of Busch, who was running in his 200th marathon to honor her brother, Air Force TSGT Brian Theobald. Brian, an Iraq veteran, took his life in July after battling post-traumatic stress disorder.

“My goal is always to get publicity for these young men and am always embarrassed that the attention is given to me. People respond so well to what I am doing and that is very humbling.”

VIDEO: Sid finishing the race.

Theobald, who works as a nurse in Pittsburgh, acknowledges she knew very little about PTSD until it claimed her brother, and believes a stigma remains both inside and outside of the military. The importance of what Sid is doing, she adds, is that he is drawing attention to private organizations and charities, such as 22 Too Many, which raise awareness about PTS and provide invaluable service to members of the military.

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, about 11-20 out of every 100 veterans (or between 11-20 percent) who served in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have PTS. By comparison, about seven percent of the general population will have PTS at some point in their lives.

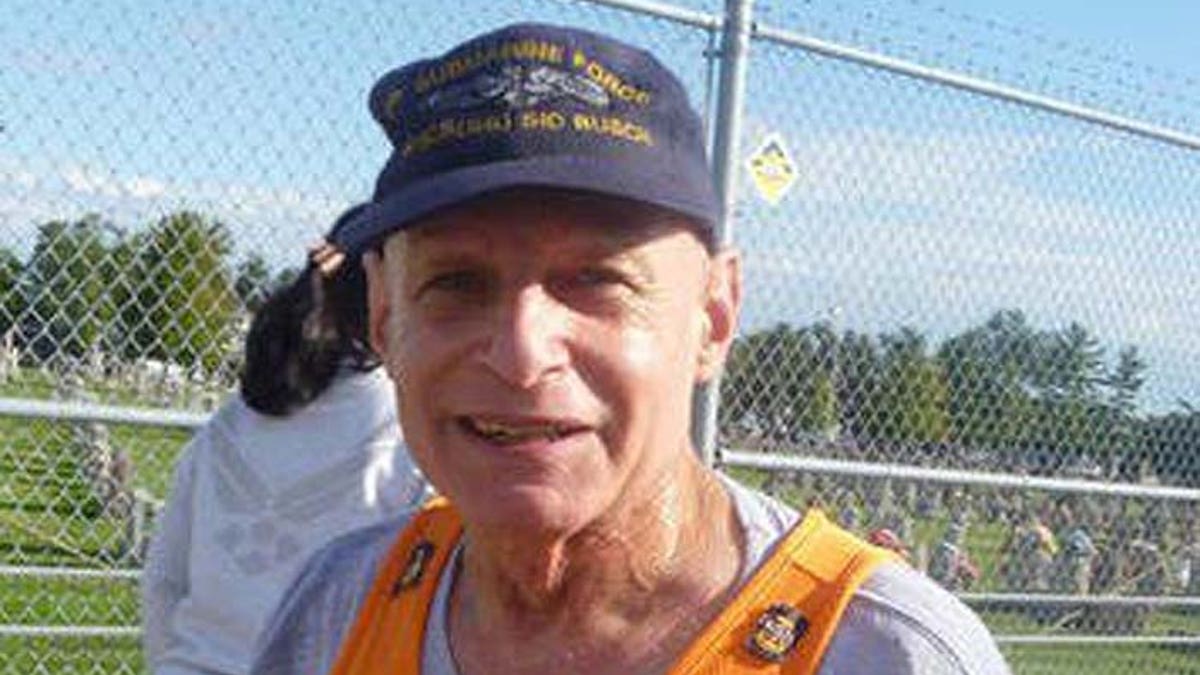

Navy veteran Sid Busch runs marathons to honor fallen service members.

Over the last decade, Busch, 69, and from Goose Creek, S.C., has become a fixture in the running community as he competes in most of his marathons and half-marathons carrying a large American flag and a picture of a fallen service member pinned to his back.

He often jokes that his slow pace ensures participants can read details of the American hero for whom he is running.

“When I go north and drive through Fayetteville, North Carolina, I always hear about a young man who has committed suicide. Not enough is being done for these kids. We send them to fight and then we expect them to be normal or to keep it inside. We have to do more,” Busch told Foxnews.com.

The 69-year-old runner recently completed his 200th race.

Busch was to complete marathon No. 200 last month in Dayton, Ohio, at the Air Force Marathon, but failed to miss the Mile 21 cut-off time. He was not disappointed that he did not reach the 200-race milestone, but that he had let the Theobald family down.

Jessica recalls the phone call they received after the race.

“We told him how wrong he was [to think he disappointed them]. He has been such an inspiration to us and to so many others,” said Theobald, who believes it was more fitting that Busch did it in Maryland where she has family and where they could make it to the race to watch him.

Most families are not present at the races Busch runs, so he sends his finisher’s medal and T-shirt to them or takes it himself to Arlington National Cemetery to place on the fallen soldier’s gravestone.

Following Saturday’s marathon finish, which Busch also dedicated to the memory of Marine Cpl. Bradley Arms, Theobald’s father presented Busch with his medal after the Navy veteran. More than 30 people, including the Theobald’s, had waited at the finish.

As he made his way through the hilly 26.2 course, it became evident that Busch’s actions over the last decade have impacted more than the families of the fallen soldiers.

“We would do anything for Sid. What he does is so inspiring and is not just a great tribute to the fallen soldiers, but to everybody who serves or has served in the armed forces who are doing the yeoman’s work,” said Lee Corrigan of Corrigan Sports, which runs the marketing end of the Baltimore Marathon.

Busch is clearly uncomfortable with the attention he receives.

“My goal is always to get publicity for these young men and am always embarrassed that the attention is given to me. People respond so well to what I am doing and that is very humbling,” he told Foxnews.com.

He was escorted throughout the entire course by four relay teams comprised of six active and retired military groups and one team made up of firefighters. Several of the team members decided to remain with Busch for the whole race. When a police motorcycle escort joined Busch at Mile 22, he initially thought it was to take him off the course because he was the last runner. He was told by one of the police officers – all of whom were off-duty at the time – that they were there to escort him home.

He admitted that the experience was incredibly humbling and was especially touched by the police helicopter which flew overhead shouting encouragement over its loudspeaker.

“I am not a man who often is at a loss for words, but I am at a loss for words,” conceded Busch after finishing the race in more than seven hours.

Busch began running marathons in 2001 and completed six marathons with his cousin, who would be killed later that same year in the World Trade Center terror attack.

“I wanted to do something to remember him, so I ran all six marathons in his honor,” says Busch, who adds that running to honor others is the least he can do to serve his nation.

“I have the easy part. What keeps me going is that it gets me so angry that the average person knows the Kardashians or someone from Hollywood, but they have no idea who these kids are. It is unacceptable. We have kids joining the military at a time when it is not safe, but they think enough of this country to go and fight and die,” says Busch.

The 2013 Air Force Marathon speaks to his commitment to those who serve. As he was running for Marine Cpl. Matt Dillon, who, like Busch, hailed from South Carolina, he began to feel an intense pain in his leg.

Busch kept running, repeatedly touching the picture of Dillon, who had earned a Purple Heart while serving in the Iraq and was killed in 2006 when he and two fellow Marines were hit by an improvised explosive device.

Busch crossed the finishing line unaware that he had done so on a broken leg.

One of the more memorable races was the one he ran for Marine Cpl. Kurt S. Shea. He was unexpectedly met at the finish by Shea’s mother, who handed Busch one of the 28 American flags that were placed in her front yard by the Marines who informed her that Shea had been killed in action.