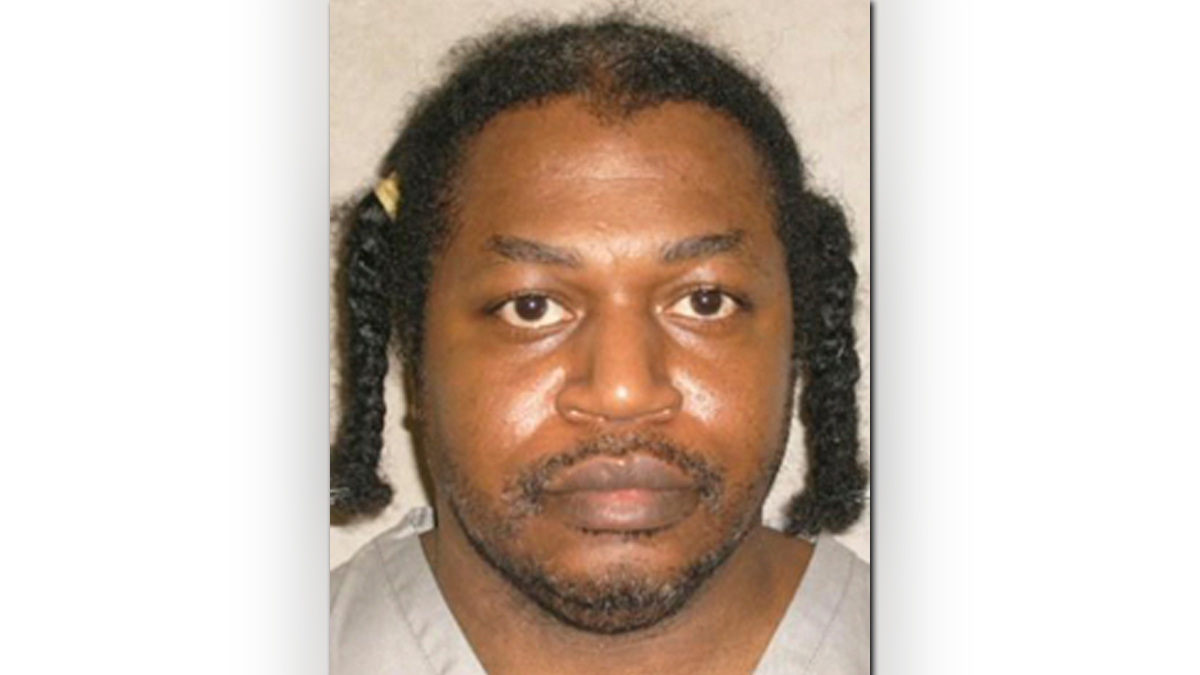

Charles Warner, who was executed on Jan. 15, 2015 for the 1997 killing of his roommate's 11-month-old daughter. Corrections officials used potassium acetate, not potassium chloride, as required under the state's protocol, to execute Warner.(AP Photo/Oklahoma Department of Corrections, File)

Oklahoma's attorney general has agreed to not request execution dates until 2016, as his office investigates why the state used the wrong drug to execute an inmate in January, according to court documents filed Friday.

Attorney General Scott Pruitt and lawyers representing death row inmates filed a joint request asking a federal judge to suspend proceedings in a lawsuit that challenges Oklahoma's lethal injection law. Both sides said the case should be put on hold as Pruitt's office investigates how the state twice got the wrong drug to use in executions.

A federal judge needs to approve the request, which comes a week after a judge put all eight of Arkansas' scheduled executions on hold because of a lawsuit challenging a state law that blocks prison officials from releasing information about where they get execution drugs. Oklahoma has a similar law, which also is being challenged by inmates.

Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin called off the execution of inmate Richard Glossip just hours before his lethal injection was scheduled to begin on Sept. 30, after prison officials said they received potassium acetate instead of potassium chloride, which is the specified final drug in Oklahoma's three-drug lethal injection protocol.

A week later, a newly released autopsy report showed that Oklahoma actually used potassium acetate to execute Charles Warner in January, contradicting what the state publicly said it had used in the lethal injection. Warner had originally been scheduled for execution in April 2014 -- the same night as Clayton Lockett, who writhed on the gurney, moaned and pulled up from his restraints before dying 43 minutes after his initial injection.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has issued indefinite stays for Glossip and two other inmates who had been set for execution this year.

Friday's court filing said Pruitt won't request any execution dates until at least 150 days after his investigation is complete, the results are made public, and his office receives notice that the prisons department can comply with the state's execution protocol.

"My office does not plan to ask the court to set an execution date until the conclusion of its investigation. This makes it unnecessary at this time to litigate the legal questions at issue," Pruitt said in a statement.

An attorney for the inmates didn't immediately respond to a request for comment Friday.

The autopsy report prepared after Warner's execution on Jan. 15 describes the instruments of death in detail. It says the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner received two syringes labeled "potassium chloride," but that the vials used to fill the syringes were labeled "single dose Potassium Acetate Injection."

That contradicts the official execution log, initialed by a prison staffer, which said the state properly used potassium chloride to stop his heart, according to a copy obtained by The Associated Press.

The next inmate scheduled to die was Glossip, who came within hours of his lethal injections before prison officials informed the governor that they had received potassium acetate instead of potassium chloride from a pharmacist, whose identity is shielded by state law. That discovery prompted new questions about past executions, including Warner's.

Prison authorities discovered the error as they prepared for Glossip's execution and immediately contacted the supplier, "whose professional opinion was that potassium acetate is medically interchangeable with potassium chloride at the same quantity," according to Oklahoma prisons director Robert Patton.

But experts on pharmaceuticals and chemistry told the AP that differences between the two forms could be relevant, including that potassium chloride is more quickly absorbed by the body and that more potassium acetate may be needed to achieve the same effect.