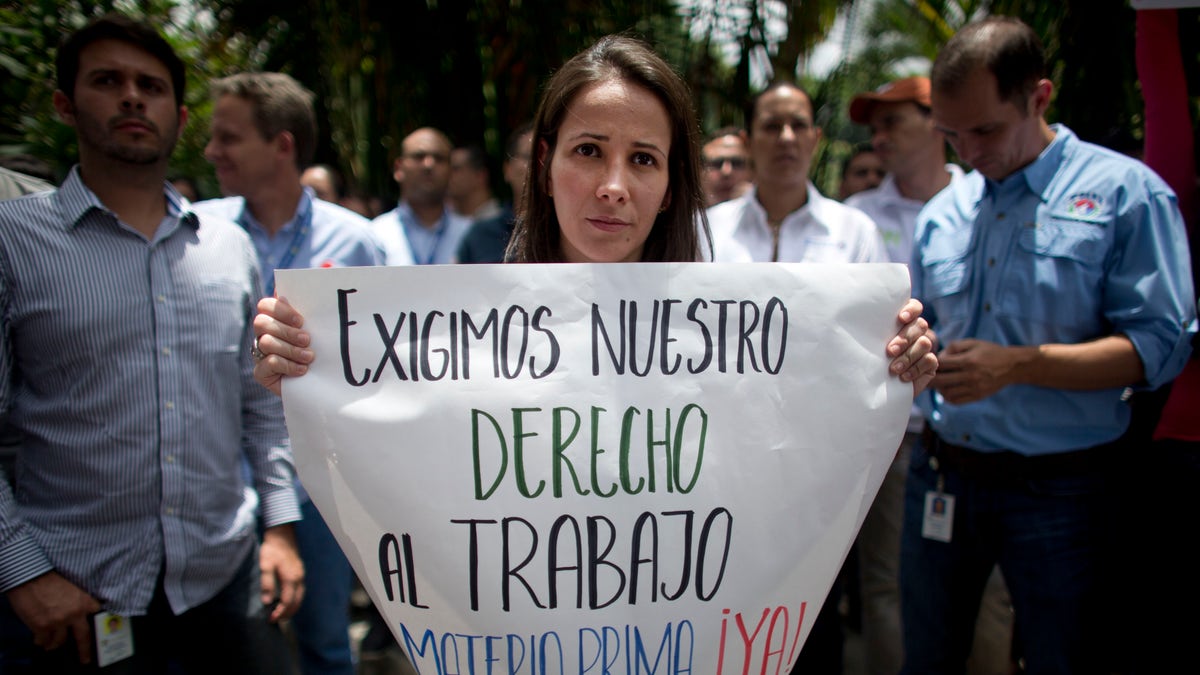

A Polar worker holds a sign that reads in Spanish: "We demand our right to work. Raw material now!" during a protest by workers who fear losing their jobs, outside company headquarters in Caracas, Venezuela, Friday, April 22, 2016. Polar, the largest producer of beer in the country, said Thursday the lack of imported raw materials could force them to stop producing beer starting April 29, when their current stock of malted barley would run out. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos) (ap)

Caracas – After President Nicolas Maduro's announcement that public offices in Venezuela will now open only Mondays and Tuesdays, many employees are saying they will use the time off to stand in the crawling food lines that have become a common sight throughout the country.

Employees will see no changes in their salary, Maduro said during the televised announcement.

Victor Urbaez, who works at the state-owned communications company Cantv, said he has mixed feelings about the new measures.

"Seventy percent of Cantv employees reject this decision,” Urbaez, who is a union member, told Fox News Latino. “We think it affects production and, even though we are getting paid, we will be unable to do the overtime work that increased our wages," he said.

Most Venezuelans reacted with disbelief to the news of the two-day workweek, a new emergency measure looking to contain the growing energy crisis.

The only exception is public hospitals, which will keep working regular hours. Public schools will be closed on Fridays.

The water level at the nation's largest dam has fallen to near its minimum operating level due to a severe two-year drought — Guri’s dam, outside Caracas, provides 70 percent of the electricity used in Venezuela.

The country's socialist administration already gave nearly 3 million public workers Fridays off earlier this month, and on Monday initiated daily four-hour blackouts around the country.

Yet experts say it is unlikely the new measures will produce a real positive effect on the electricity crisis, since 63 percent of the country’s energy consumption is residential, according to official data — if people are not working or studying, the reasoning goes, they will be in their houses consuming more energy.

And it is in the households where plans to save electricity have proved less effective.

“If you have 30 children in a classroom, they are just using electricity for lights, but if they are at home many will turn on their computer or TV,” said Leonardo Carvajal, a pedagogue and professor at the Universidad Catolica Andres Bello.

Venezuelan law requires 200 school days per academic year. Carvajal calculates that the number will be cut to around 150 this year.

“This hurts the normal learning pace of children,” he said. “Schools are not companies. If you lose one day, it is not easy to recover it later on,” he told FNL. “Children have a certain working capacity and they can’t work extra hours that easily.”

And yet Maduro said the five-day weekend is the only way to prevent a total energy collapse, a threat that meteorologists forecast will end with rain finally arriving steadily on the second week of May.

Having public employees working just two days a week is expected to be an inconvenience for millions of Venezuelans.

People planning to leave the country will be among the most affected.

Jose Marquez, for instance, is a 27-year-old journalist whose plans to emigrate to Argentina in July are now jeopardized by the reduced workweek.

“I need an official copy of my criminal records, which normally you get in 15 working days. But now I don’t know how much time it will take,” he said. “I am worried because I don’t want to lose my airplane ticket,” Marquez explained FNL.

The process of obtaining school certifications and university diplomas, which used to take six months or more, will now extend dramatically as well.

“I have a job opportunity in Mexico,” said Elizabeth Montanes, a 29-year-old dentist, “but I need to certificate my high school diploma as quickly as possible and I don’t know if I will be able to make it.”

Marquez said before leaving Venezuela he wants make sure his mother has a passport. They had an appointment scheduled for today, he said, but since the office didn’t open they are uncertain how long it will take.

“We went there and no one gave us official information about what to do. The only person there was the security guard, and he said that appointments will be rescheduled and we should wait,” Marquez added.

The AP contributed to this report.