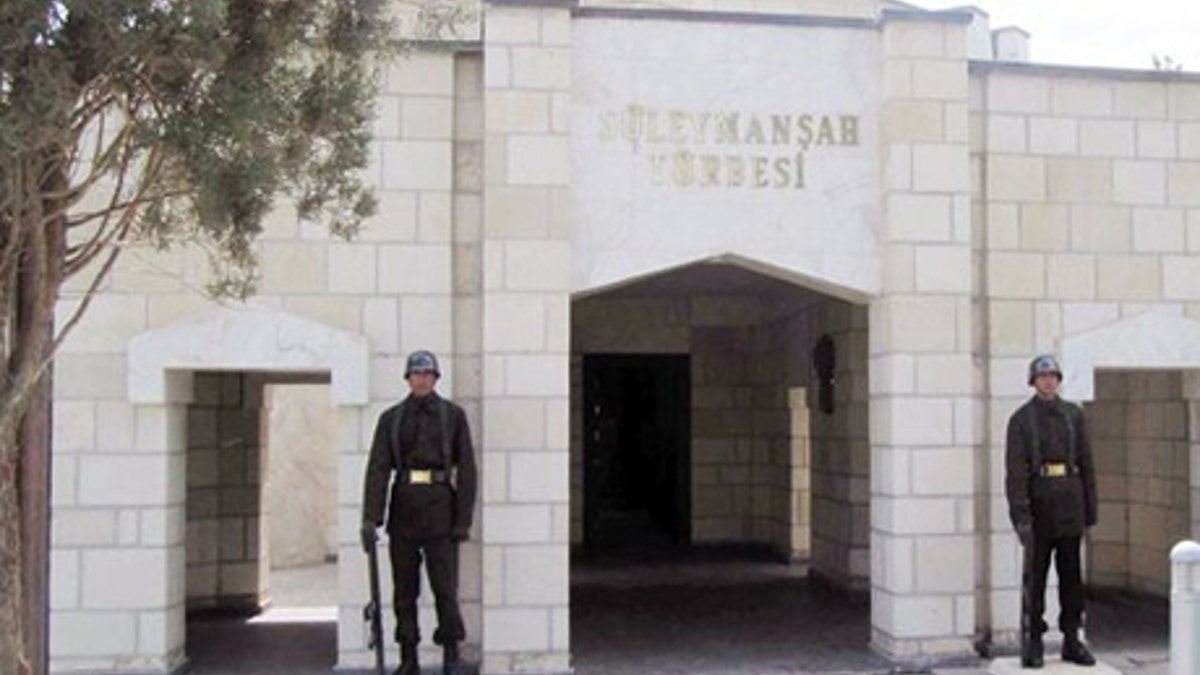

April 7, 2011: Turkish soldiers stand guard at the entrance of the memorial site of Suleyman Shah, grandfather of Osman I, founder of the Ottoman Empire, in Karakozak village, northeast of Aleppo, Syria.

ISTANBUL – It's a tiny plot of Turkey deep within violence-torn Syria -- a sacred mausoleum guarded by Turkish troops.

The memorial to Suleyman Shah, grandfather of Osman I, founder of the Ottoman Empire, has remained surrounded by a small contingent of Turkish soldiers even as Turkey helps to lead international condemnation of the Syrian regime, shutting its embassy in Damascus and demanding that President Bashar Assad resign.

Few travelers visited the tomb even before the Syrian government's violent crackdown on an uprising that began more than a year ago. But the site along the Euphrates River is revered by Turkey, a strongly nationalist country whose rights there stem from a 1921 treaty with France, then colonial power in Syria.

The Ottoman empire collapsed in the early 20th century, and foreign powers encroached on its former territories. An article in the 1921 Franco-Turkish agreement lets Turkey keep guards and hoist its flag at the Syrian tomb, described as Turkish property. The arrangement was renewed with an independent Syria.

"Our soldiers are still there. There is no problem at all," a Turkish military officer said on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

Still, sensitivities are extreme at a time when Turkey, and its Western and Arab allies, campaign for the downfall of the Syrian government and urge the Syrian opposition, including rebels, to unify. While Syria has not interfered with the Turkish soldiers, believed to number about a dozen, the instability sweeping the nation could pose problems to a tradition that seems to defy political realities.

Syria has made no public statements about the soldiers, possibly calculating that any move against them, particularly at a site heavy with Islamic symbolism, offers no political gain and only risks retaliation from its powerful neighbor. Turkey's military headquarters declined to talk to The Associated Press, a likely sign that it does not want to publicize the memorial amid Syria's chaos.

"This is a kind of a risk for Turkey," said Osman Bahadir Dincer, a Syria expert at the International Strategic Research Organisation, a center in Ankara, the Turkish capital. "If someone really wants to pull Turkey into the problem, they can use these soldiers as a provocation."

By that, he meant an attack or harassment of the troops at the fenced compound on a strip of land jutting into the water near the village of Karakozak, about 25 kilometers (15 miles) from Turkey. Most of the thousands of Syrian refugees who have crossed the border used routes west of the village. Turkey's consulate in Aleppo, southwest of Karakozak, remains open.

Pro-Assad groups in Syria are increasingly hostile to Turkey, which has considered establishing a buffer zone inside Syria if border security deteriorates, and some anti-government activists hope foreign militaries will feel compelled to intervene and topple Assad.

Photographs of the memorial, taken in recent years, show ramrod-straight sentries with rifles. Red and white Turkish flags fly on tall poles on the tended, lush-green lawn.

A Turkish battalion based near the Syrian border rotates units at the mausoleum, and there are no indications that this process has been disrupted despite the tensions. Turkey has urged its citizens to leave Syria, and its diplomatic missions were the target of angry protests by pro-Assad demonstrators.

In a 1970s agreement with Syria, Turkey moved the mausoleum, sacred in Turkish lore, to its current location because the old site at a castle further south was to be inundated by the waters of a new dam.

Soner Cagaptay, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, visited in 2006 and described it as a "surreal experience."

He said the surrounding landscape was desolate -- "there are no towns, tiny small villages here and there" -- and that he had to show his passport to enter. The soldiers seemed bored. The infrequent visitors who signed the log were mostly Turks or ethnic Turks from Germany, Azerbaijan, the United States and other countries.

"It's a mini-attraction," Cagaptay said. "It's like a mythical past. It is where it all started for the Turks in Turkey."

Shah, a Turkic leader, is said to have drowned in the Euphrates in the 13th century. His followers headed north into what is today Turkey, where they launched the Ottoman empire. Some historians question official accounts about Shah's tomb, saying they might have been retrospectively concocted to enrich an imperial, then national identity for Turks.

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey's founder, rejected the legacy of the Ottomans and their Islamic precepts, deeming them backward and imposing a secular, Western-oriented outlook that remains the subject of national debate today. In Shah, though, he may have seen a link to Turkic origins in Central Asia, a source of veneration in his new order.

"Even Ataturk could not let go despite the fact that his reforms were so much about letting go of the Ottoman past," Cagaptay said. The mausoleum's newfound vulnerability in a country in conflict, he said, makes it potentially "more significant than it has ever been since the end of the Ottoman empire."