The violent fight for Yemen’s capital

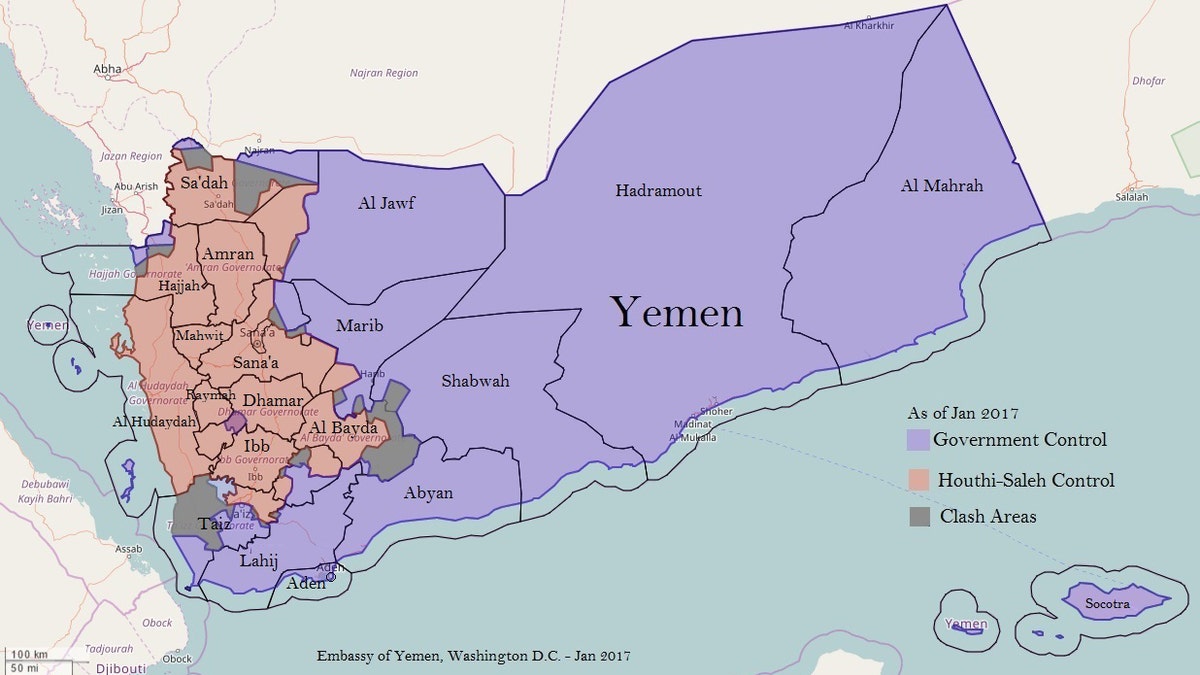

The Yemeni civil war rages on as the Saudi Arabian-led coalition supporting Yemen’s internationally recognized government tries to take back the capital city of Sana’a.

SANA’A, Yemen – A scattered array of soldiers, their weather-worn faces signaling the toll of war, make their way along a narrow, winding dirt track across the serrated terrain of Nihm Mountain to hunt enemy hideouts, just 13 miles east of the Houthi-controlled center of Sana’a city.

The soldiers, loyal to the Yemeni government’s exiled President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, sing patriotic battlefield songs as they set their sights on the gutted Sana’a airport in the distance.

“We come under a lot of fire every day,” Commander Yahya Hatemi, who leads the throng of young men in the area, told Fox News during a front-line visit. “They must have just woken up . . . You can hear the shouting.”

The “shouting” is, of course, the rumble of incoming artillery, which seems to do little to perturb the array of hardened fighters.

Even though the battle is still far from being victorious for either side, Nihm Mountain is of extreme significance in the official Yemen forces’ protracted quest to take back their nation’s capital, Sana’a. The Iran-backed Houthi militias seized the city in September 2014, prompting a Saudi Arabia-led coalition supporting Yemen’s internationally recognized government to embark on a bombing campaign, heavily condemned by human rights groups and international governments, across its border.

“They sleep until noon and then start chewing khat,” Hatemi said of the Houthi’s routine chomping on the widely used Yemen drug of choice. “And then they get moving.”

But khat is seemingly not the only substance casually proliferating through the battlefield. According to several Yemeni military leaders and medical personnel, Captagon -- the meth-like variant of the banned pharmaceutical Fenethylline, which is often manufactured in and trafficked out of Lebanon -- is also being used across enemy lines, as it was under ISIS command, to keep young rebels hard-wired and fearless in attacking.

“There is that and witchcraft, too,” Hatemi vowed. “Making young fighters believe they are protected from all bullets.”

Intelligence findings, according to the forces in the Sana’a governate, also claim that the “uneducated and poor” are preyed upon by the Houthis to take up arms and in many cases are made to believe that they are fighting “America and Israel” rather than their own countrymen.

Moreover, an estimated 60,000 landmines have been planted on Sana’a city’s rim, taking the lives and limbs of those who dare to flee.

In one case, documented with photographs to Fox News during an evacuation and humanitarian briefing this week by the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Defense, a 3-year-old girl named Jameela had her hair chopped off so she would resemble a boy during a rescue by the agency’s child protection unit. Jameela had been recruited for use as a human shield to those planting the explosives.

While the case could not be independently verified, numerous military officials, activists and residents from the region bemoaned that children -- including in rare circumstances young girls -- are being forcibly propelled to imbed such deadly devices.

“We know the Houthis are becoming weaker because now they are trying to recruit from schools and houses by force,” Hatemi charged.

The Houthi insurgents once controlled Nihm peak too, before Yemeni forces reclaimed it in a bitter fight about eighteen months ago.

Yet almost three and a half years since the conflict eruption, Sana’a remains so close yet doggedly so far.

Since the war’s beginning, the United Nations has accused both sides of waging deadly attacks in violation of international law, in which civilians have weathered the brunt of collateral damage.

However, Hatemi insists that the reason it has zig-zagged along the difficult and dangerous ridges and has stalled on their push forward to capture Sana’a is first and foremost to protect the villagers nearby from being swept up into the bloodshed.

Meanwhile, in the endless hours spent fighting and waiting to fight, the young soldiers share their memories of Sana’a. One young man whimsically recalls his time behind bars, having been caught by Houthi leaders taking photos shortly after the city’s takeover in 2014. One year into his tortuous time, a bomb hit the facility and he was able to flee amid the chaos.

Others speak of the friends and family among those who have “been disappeared” into the dark void of the violent region.

'Last month, we killed at least 1,200 Houthis and we have killed tens of thousands since the beginning.'

As if on cue, in full tilt of the afternoon sun, a Houthi target is spotted close by. Two soldiers, almost childlike in their stature, climb aboard the ZPU-2 anti-aircraft gun mounted on a truck, which consists of two KPV 14.5-mm. heavy machine guns and begin firing.

Within minutes, the Houthis retaliate with incoming rounds of their own, gashing into the hardened mountain crust.

Despite the heavy and constant combat, Hatemi and his men don’t wear body armor in the mountains -- they say it slows them down -- and are protected by little more than AK-47s and a tenacious faith in God.

He surmises that around 13,000 of his fellow Yemeni fighters have been killed in action since the war’s 2015 inception. While painful, the commander contends it’s nowhere near the number of Houthis taken down in the conflict.

“Last month, we killed at least 1,200 Houthis and we have killed tens of thousands since the beginning,” Hatemi boasted. “But the number doesn’t matter to us; we consider them to be like slaves. Yemen people are peaceful people, but what the Houthis stand for is death and destruction.”

However, the Houthis -- or as they formally refer to themselves “Ansar Allah” meaning “helpers of God” -- have a markedly different take from their side entrenched in the city and its surroundings. Shielded by local tribes protecting the city’s periphery, the rebel group has made it clear that they have no intention to simply surrender. The leadership maintains that they are resisting the rampant government corruption and the rise of Sunni-Islamist militant groups that expanded under Hadi’s leadership.

But the longer the war drags on, the more civilians will pay the price. The conflict so far has displaced more than 3 million, left vast swaths of the population on the brink of starvation, killed or wounded more than 13,000 non-combatants and provided a turbulent tableau for Yemen’s potent Al Qaeda affiliate to quietly carve out its base of operations.