WASHINGTON – People make poor economic choices. They don't save enough for retirement. They refuse to cut their losses on plummeting investments. They buy houses and stocks when prices are high, thinking that what's going up today will keep going up tomorrow.

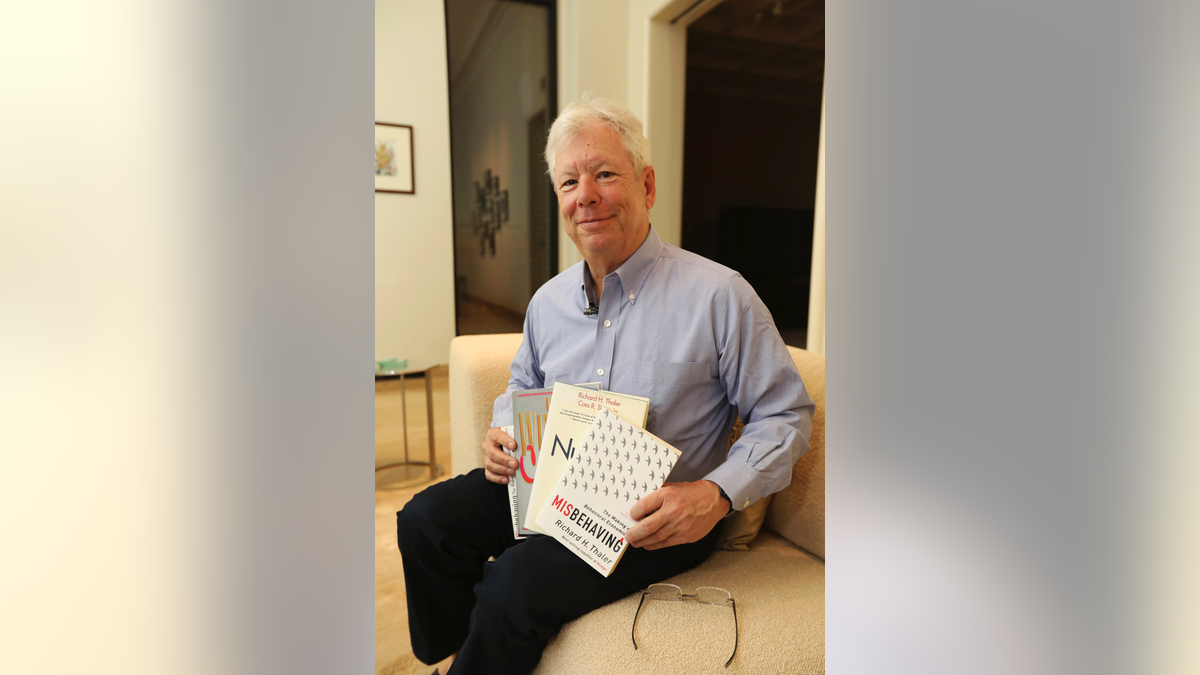

Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago on Monday won the 2017 Nobel prize in economics for documenting the way people fail to conform to models that assume they always act in their own self-interest. As one of the founders of behavioral economics, Thaler, 72, has helped change the way economists look at the world.

"Thrilling news," said Thaler's frequent collaborator, Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law School. "He changed economics, and he changed the world."

Far from being the rational decision-makers described in economic theory, Thaler found, people often make decisions that run counter to their best interests. And their actions carry far-reaching economic consequences: Baby boomers failed to save enough for old age. Americans kept buying homes as prices soared above levels that made any economic sense in the mid-2000s, creating a bubble that led to a devastating financial crisis and recession.

To contain the damage from such collective actions, behavioral economists say, policymakers must recognize human irrationality.

"I try to teach people to make fewer mistakes," Thaler said in an interview Monday with The Associated Press. "But in designing economic policies, we need to take full account of the fact that people are busy, they're absent-minded, they're lazy and that we should try to make things as easy for them as possible."

Thaler's work is grounded in day-to-day reality and is connected to popular culture in a way that isn't always true of Nobel-winning economists.

"He's made economics more human," said Peter Gardenfors, a member of the prize committee.

Thaler provided a cameo alongside pop star Selena Gomez in the film "The Big Short." He once analyzed the flawed strategies of participants in the game show "Deal or No Deal." He's assessed how taxi drivers decide to spend their days and how school cafeterias should display their food.

Thaler won the 9-million-kronor ($1.1-million) prize for "understanding the psychology of economics," Swedish Academy of Sciences secretary Goran Hansson said Monday. He is the 13th Nobel-winning economist from the University of Chicago.

Oddly, the University of Chicago is closely associated with the classical economic views that Thaler has spent much of his career challenging.

"There's nothing people like better at the University of Chicago than a good argument," Thaler said.

In fact, Thaler is the golfing buddy of an intellectual rival, Eugene Fama, the classical Chicago economist who won the Nobel in 2013 for arguing that financial markets are rational.

Asked by phone at a news conference what he planned to do with the prize money, Thaler joked that he intended to spend it "as irrationally as possible."

Speaking with the AP later, he offered a fuller response that drew on the philosophy of his work.

"In traditional economic theory, it's a silly question. And the reason is that money doesn't come with labels. So once that money is in my bank, how do I know whether that fancy bottle of wine I'm buying (is being paid for by) Nobel money or some other kind of money? The serious answer to the question is that I plan to spend some of it on having fun and give the rest away to the neediest causes I can find."

People's irrational classification of different pools of money is, in fact, fundamental to Thaler's research. He has found that the tendency to assign money to certain categories can lead to costly mistakes. For example, consumers might spend more than they need to when they put, say, a new washing machine on a high-cost credit card because they don't want to tap money they've labeled as savings.

In one study, Thaler and his colleagues studied how taxi drivers try to balance making money versus enjoying their leisure time. The driver might respond by setting a goal: Once his take from fares reaches a certain amount, he calls it a day. But that would mean that he works shorter hours when demand for taxis is high and longer ones when business is slow. If he took another approach, he could make more money working fewer hours. And there would be more cabs in the street when customers need them.

Thaler and other behavioral economists also found that people hold notions of fairness that confound classical economic expectations. They resent, for example, an umbrella peddler who raises prices in the midst of a downpour. Traditional economists would say the peddler is just responding to increased demand.

Thaler says that kind of thinking can keep people from buying things they'd enjoy. A supporter of baseball's Chicago Cubs, Thaler suspects that some of his fellow fans will balk at paying higher-than-usual prices this week to see their team play the Washington Nationals in the playoffs. (He says he secured tickets for Tuesday's game "at a very reasonable price.")

But consumers' strong feelings about fairness pose a threat to companies, too. They should think hard before raising prices aggressively — even when it's seemingly justified by surging demand — or risk alienating their customers.

"Uber has learned this lesson or is in the process of learning it," Thaler says. "When they surge-price during a blizzard in New York, that's not a smart business decision."

Thaler's research carries implications for economic policy. In their 2008 "Nudge" book, Thaler and Sunstein suggested that policymakers should find ways to coax, rather than coerce, proper decisions.

Suppose a cafeteria staff realized that students choose food based on the order in which it is presented. It would make sense, Thaler argues, for the school to put the healthiest food where kids would be most likely to grab it. Some critics call such policies manipulative. But Thaler argues that the food has to be displayed somehow; why not choose the one that promotes good health?

Thaler says behavioral economics isn't as novel as is normally assumed. Adam Smith, author of the 1776 classic "The Wealth of Nations," dealt with behavioral issues in his time, including the need to control impulses and avoid overconfidence.

But after World War II, Thaler says economics became dominated by mathematical models. And those were easier to use if economists assumed that people always acted rationally. The mathematical approach "caused some of the people in the profession to take those assumptions more seriously than they should have."

A series of financial crises, including the dotcom crash of 2000-2001 and the collapse of the American housing market in the mid-2000s, have put a dent in the view that people and markets are rational.

"Each crisis," he says, "has been good for behavioral economics."

___

Heintz reported from Moscow. David Keyton in Stockholm and Matt Ott in Washington contributed to this report.