International leaders scramble to assemble Libyan gov't

Political leader speaks out about border security

With ISIS expanding in Libya, getting ever closer to prized oil fields, and ramping up its propaganda from the northern African state, there is a sudden flurry of diplomatic activity to get a functioning government into place.

A meeting of foreign ministers from dozens of countries will take place in Rome Sunday. Friday in Tunis, the UN Envoy for Libya announced that the two rival governments that currently exist in Libya had come to an accord about forming one unity government. Successive Libyan governments have failed post-Qaddafi. This latest UN-backed unity government deal is already coming under fire from a group of prominent Libyans, parliamentarians of the same two rival governments party to the UN deal.

Awad Abdelsadig and Ibrahim Amaish, of the Tripoli and Tobruk governments respectively, signed a different unity accord just last weekend, also in Tunis, making headlines for the very fact that they had come together without outside intervention or guidance, apparently finally resolving the elusive task of getting opposing sides together to keep Libya from becoming a truly failed state. They want to return to Libya's 1951 constitution, but without a king. The UN deal subsequently announced, involves different structures and different players for the running of Libya. How the fact that Libya went from having two opposing disparate governments on opposite ends of the country, to having two rival unity government plans will affect the situation on the ground is unclear.

The confusion comes in a week when rumors about the ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, being in Libya, were rife. There has been no reliable confirmation of this. Ibrahim Amaish, of the House of Representatives of the Tobruk government and a broker of the first unity government deal, thinks Baghdadi is only the tip of the iceberg.

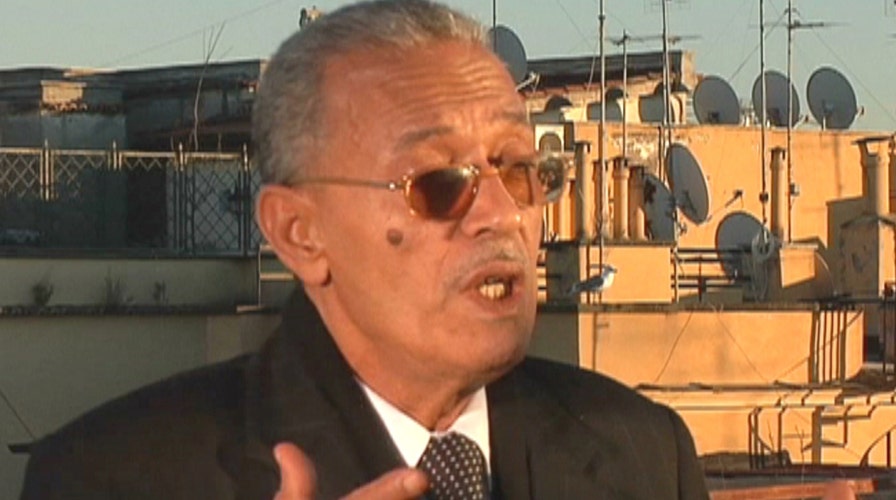

"There is not one Baghdadi; there are tens of Baghdadis. When you see that our country, the borders of our country, are completely open. We can't control them. We need your help. We are all suffering from this."

Meanwhile, his counterpart from the other side, Awad Abdelsadig, responds to the speculation that with ISIS under heavy attack now in Iraq and Syria, it may be seeking to form a backup caliphate in lawless Libya.

"Yes, I am worried about that. We need help, just help. In Libya the people are very educated, we have relationships with Europe and the United States and if the world would just help us, we will make our country a very great country soon."

A former Western military commander with vast experience in Libya wonders how any of the independent bureaucrats who make up these governments will manage to control the tribes and the militias he says are the real power in Libya right now.

Awad claims the tribes were united in the early days after the revolution and believes that cohesiveness can somehow be re-established. However, for now the magic formula is either under wraps, or simply doesn't yet exist.

Awad says on the one hand, Libya doesn't want foreign interference; on the other it wants help -- it would like countries such as the United States to get certain Arab states to stop supporting different players with arms and money.

Money is a pivotal part of the story. It is in very short supply in the country, but in abundance abroad. Whoever unlocks Libya's deadlock will have access to frozen billions, if not trillions, of Qaddafi cash, while in the meantime, Libya's poor live a miserable existence.

Human trafficking is one of the most notorious industries in Libya today. Neither rival government has proven able to stop the flow of boatloads of immigrants from its shores, across the Mediterranean to Italy. Italians until now have played down the possibility that these boats could be used to smuggle terrorists into Europe, but after the deadly attacks in Paris, where at least one of the suicide bombers came from Syria via boat, the story has changed. Libya has little control of who passes through its country, so has little incentive to hold onto any of the refugees who come through. A strong Libya would be able not only to stop the traffickers' boats, but would be able, once its economy gets back on its feet, to help neighboring countries feeding many of the migrants develop, and create prospects to incentivize citizens to stay in their homelands.