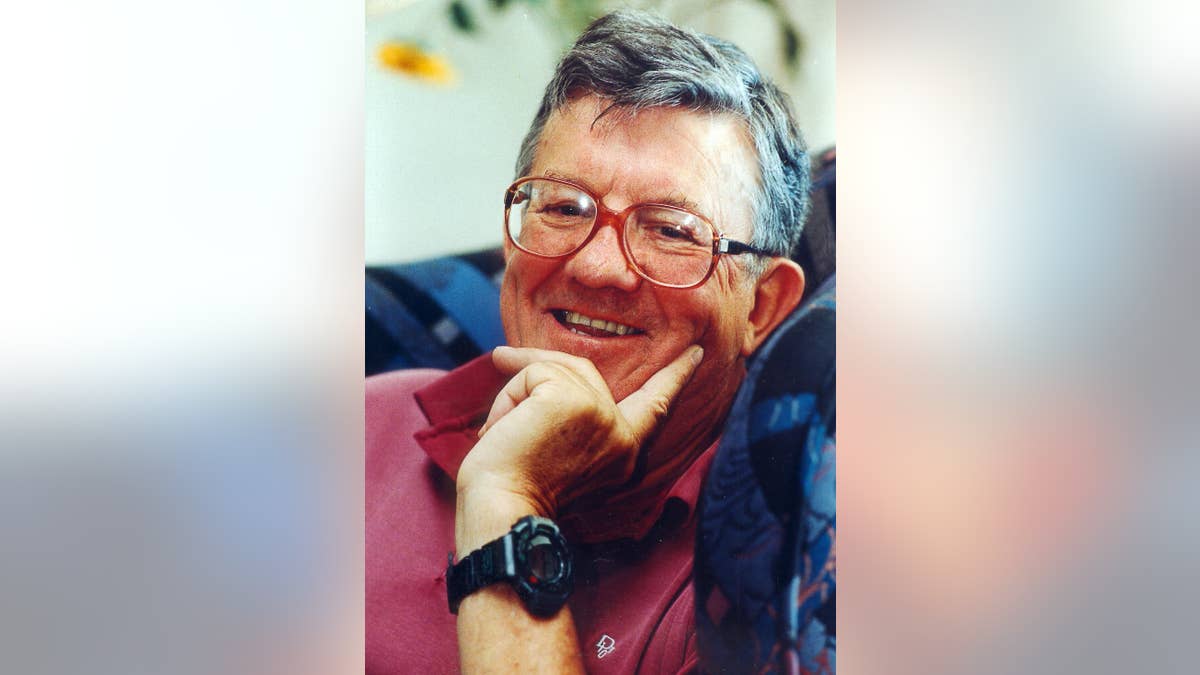

In this undated photo supplied by the Sunday Times newspaper former editor, Ken Owen, is photographed in Johannesburg. Owen died of cancer March 19, 2015 at his home in Cape Town, South Africa aged 80. (AP Photo/Sunday Times) (The Associated Press)

JOHANNESBURG – "All offended?" former South African newspaper editor Ken Owen asked an audience of friends and family in a speech marking his 80th birthday.

Owen, a tenacious force in journalism in the last years of white racist rule, delivered trademark zingers at the Feb. 21 gathering hosted by his wife, a month before he died of cancer. He warned of a creeping authoritarianism in South Africa's ruling African National Congress and said elections won't stop it.

"Once in five years we get a chance to voice our disapproval, a futile exercise," Owen said. One of his sons, Richard Moultrie, said Tuesday that Owen appeared weak, tired and typically determined during what amounted to a final farewell at his Cape Town home before his March 19 death.

He was remembered as brilliant and cantankerous, an editorial writer who led South Africa's big newspapers when the world was transfixed by the struggle against apartheid and the transition to democracy in 1994. Owen was editor of the Rand Daily Mail and the Sunday Express, both of which folded in the 1980s, as well as Business Day and, between 1991 and 1996, The Sunday Times.

"South Africa's Last Great White Editor," declared a 1996 profile of Owen in the Mail and Guardian newspaper, which printed his final speech after his death.

Owen unleashed searing editorials in all directions, harshly criticizing P.W. Botha, one of apartheid's last presidents, warning of communist influence in the liberation movement fighting white minority rule and slamming the alleged hypocrisy of white liberals who called for change but enjoyed institutional privileges.

"His byline was a drawcard," said Peter Honey, a former journalist. "He was an elegant, balanced writer and a piercingly perceptive reporter — one of a small number of South African journalists with the understanding and ability to describe the country and its people in a universal context."

Charlene Smith, a Sunday Express reporter in the early 1980s, recalled arguing with Owen over an article she wrote on how the African National Congress, then the main anti-apartheid movement whose leaders were mostly in exile, was gaining ground in South Africa. A skeptical Owen wanted to change part of the story, but Smith refused.

"The whole newsroom went quiet as they expected him to explode, fire me, throw me out of a window or do something dramatic," Smith, now a U.S.-based writer and consultant, wrote in an email to The Associated Press. "Instead, he said, 'OK, we'll run it as you wrote it.'"

Owen could be so fickle that some people at The Sunday Times "said he was influenced by the moon," Smith wrote. She said: "He liked passionate journalists but you had to be able to argue your position, he needed to believe that you'd done the work, that you'd gone out there and that you were prepared to risk everything for your work."

After apartheid, Owen wrote with some optimism about a country dubbed the "rainbow nation" for a relatively peaceful transition from a government led the white Afrikaner minority to black majority rule.

"This country is a transformed place, with the Afrikaners subdued and turning out to be awfully nice people on the whole," he wrote to friends in 1999. But he suggested the new political debate was mundane, saying: "I can't really get worked up by shabby parish-pump politics. Not after the way it was."

In his last speech — actually delivered three days after his Feb. 18 birthday — Owen spoke of "the tender and loving care I received from a bunch of drunks when I crawled into Alcoholics Anonymous 45 years ago," as well as the "fairy book love story" of life with wife Kate.

He recited a comment attributed to William the Silent, the 16th century leader of a European revolt: "It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake, it is not necessary to succeed in order to persevere."

And Owen said to his friends: "While it is a joy to see you, I must say to you that I relinquish life easily, and I hope gracefully. It is time to go."