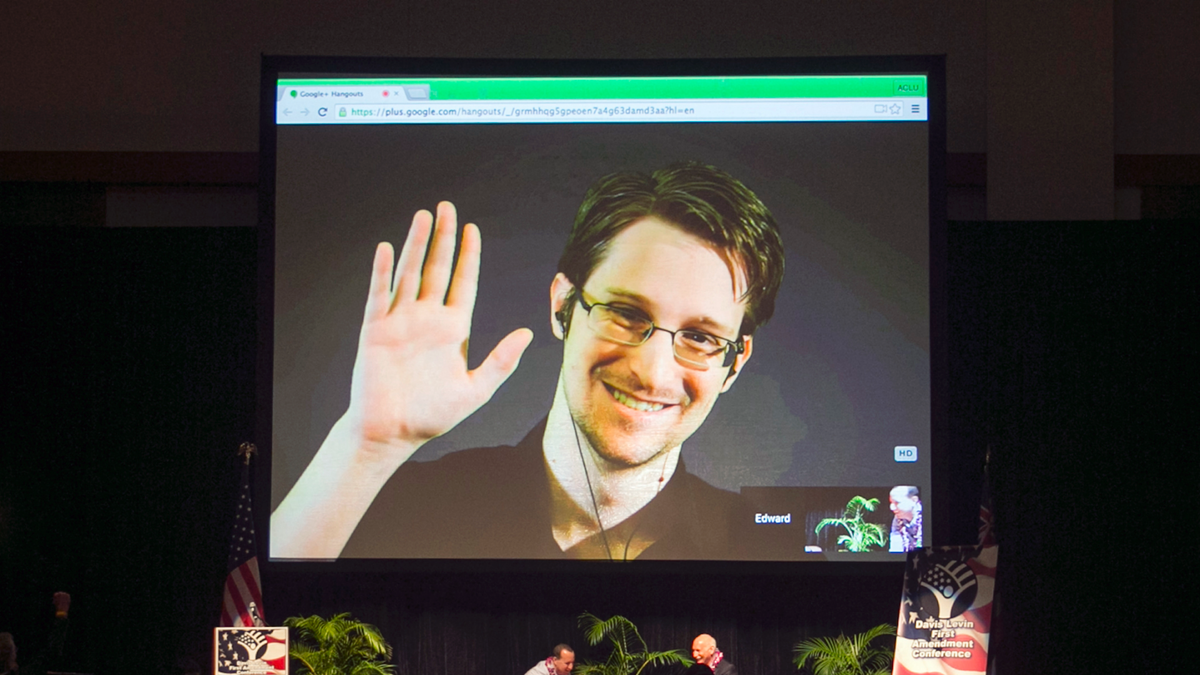

FILE - In this Feb. 14, 2015, file photo, Edward Snowden appears on a live video feed broadcast from Moscow at an event sponsored by ACLU Hawaii in Honolulu. Europe's human rights court is about to publish what could be a landmark ruling on the legality of mass surveillance. The case brought by civil liberties, human rights and journalism groups and campaigners challenges British surveillance and intelligence-sharing practices revealed by American whistleblower Edward Snowden. (AP Photo/Marco Garcia, File)

STRASBOURG, France – Europe's human rights court handed a partial victory Thursday to civil rights groups that challenged the legality of mass surveillance and intelligence-sharing practices exposed by American whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that some aspects of British surveillance regimes violated provisions in the European Convention on Human Rights that are meant to safeguard Europeans' rights to privacy.

Specifically, the court said there wasn't enough independent scrutiny of processes used by British intelligence services to sift through data and communications intercepted in bulk.

The ruling cited a "lack of oversight of the entire selection process" and "the absence of any real safeguards."

The court's seven judges also voted 6-1 that Britain's regime for getting data from communications service providers also violated the human rights convention, including its provisions on privacy and on freedom of expression.

But the ruling wasn't all bad for British spies. The court said it is "satisfied" that British intelligence services take their human rights convention obligations seriously "and are not abusing their powers."

The court also gave a green light to procedures British security services use to get intelligence from foreign spy agencies, saying the intelligence-sharing regime doesn't violate the convention's privacy provisions.

The ruling is not final and could be appealed.

Civil liberties campaigners who brought the case hailed the judgment as a landmark victory against the mass surveillance that governments have defended as an important tool in fighting terrorism.

Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch, said the ruling "vindicates Mr. Snowden's courageous whistleblowing."

"Under the guise of counterterrorism, the U.K. has adopted the most authoritarian surveillance regime of any Western state, corroding democracy itself and the rights of the British public," Carlo said in a statement. "This judgment is a vital step towards protecting millions of law-abiding citizens from unjustified intrusion."

Dan Carey, a lawyer for the complainants, said: "There needs to be much greater control over the search terms that the government is using to sift our communications."

Caroline Wilson Palow, another of the plaintiffs' lawyers, said the ruling "confirms that just because it is technically feasible to intercept all of our personal communications, it does not mean that it is lawful to do so."

The British government said it would give "careful consideration" to the court's findings.

It noted that the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which was the subject of the challenge, had been replaced by new legislation in 2016.

"This includes the introduction of a 'double lock' which requires warrants for the use of these powers to be authorised by a Secretary of State and approved by a judge," the government said in a statement.

"An Investigatory Powers Commissioner has also been created to ensure robust independent oversight of how these powers are used."

Rights groups, though, say Britain's surveillance laws are still far too intrusive.

___

John Leicester in Paris and Jill Lawless contributed to this report.