A Coptic Orthodox bishop surveys a damaged church in late August in Minya, Egypt. Concelebrating Mass with the leader of Egypts Coptic Catholics, Pope Francis prayed for the safety and religious liberty of Christians in the Middle East. (CNS photo/Louafi Larbi, Reuters) (Dec. 9, 2013) See POPE-COPTS Dec. 9, 2013.

Prospects of Christianity surviving in its birthplace, the Middle East, appear as grim this Holy Week as they have at any time in the last two millennia.

Persecution of the world’s largest religion has intensified throughout the 20th century and that trajectory has only intensified in recent years, especially in Muslim-dominated countries. Jihadists appear to have repeatedly carried out one of their oft-stated goals of erasing any trace of Christianity in some regions, while in others persecution against Christians and other religious minorities are being held at bay — for now.

The actual prospects facing Christianity in three of its longest-standing strongholds, Syria, Egypt and Iraq, vary significantly. But a blind eye is often turned by the mainstream media and others when it comes to anti-Christian atrocities, which have become an all-too-common way of life for many in the Mideast.

What follows is a summary of challenges facing Christians in each of these three areas.

“Believing that a man named Jesus Christ was crucified and rose again for the sins of the world is still one of the most dangerous things one can do in many parts of the world.”

Egypt. Egypt's Christians, known as Coptic Christians, make up around 10 percent of the population and have long been a target not only of Islamic extremists but the majority Muslim population’s resentment of Copts.

Coptic leaders have reported that since February 2011, after the Arab Spring resulted in the election of a Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Morsi as president, persecution worsened. Since then at least 200,000 Christians have fled the country.

July 20, 2014: An Iraqi Christian family fleeing the violence in the Iraqi city of Mosul, sleeps inside the Sacred Heart of Jesus Chaldean Church in Telkaif near Mosul, in the province of Nineveh. (REUTERS)

Two years later when a military coup ousted Morsi many of his supporters blamed the Copts. As a result, violent incidents against Christians have steadily increased. And while current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has made concerted efforts to protect the Coptic community, this year has shown some of the most violent attacks against Christians.

That is especially so in Egypt’s northern Sinai region where the Islamic State is taking direct aim against Christians. Before 2011, that community numbered up to 5,000; it has now dwindled to fewer than 1,000, according to the Associated Press. There are no official statistics on the number of Christians in cities or across the country.

Saturday, December 24, 2016: Christians walk in the rain to attend Christmas Eve's Mass in the Assyrian Orthodox church of Mart Shmoni, in Bartella, Iraq. (The Associated Press)

“The Copts, like most Christians around the region, are victims of religious hatred. But they are also pawns in a larger game to destabilize ‘apostate’ Arab regimes and invite Western intervention that will, in turn, ignite Arab opposition on the street – not to mention opposition on the Western street,” Robert Nicholson said to Fox News.

Unless Sissi can bring to heel ISIS and dissipate the widespread loathing of Christians that characterizes the nation’s Muslim population, prospects for the Egyptian church appear grim.

Iraq. In 2003, Iraq’s Christian population was an estimated 1.4 million, according to ADF International. Christians enjoyed relatively many civil rights and were able to rise to high levels in private and public life. Indeed, Saddam Hussein’s foreign minister, Tariq Aziz, was a Christian. The Nineveh Plain region, also known as the Plain of Mosul, in northern Iraq was a centuries-old homeland for the country’s Chaldean, Syriac and Assyrian Christians.

Then the U.S. invaded Iraq, unleashing an orgy of sectarian violence that hammered churches. Christians fled the Nineveh Plain, and as of late last year the number of Christians in Iraq had fallen to an estimated 275,000.

One reason for the exodus was ISIS conquering northern Iraq in 2014. The terror group launched a pogrom against the church, as well as against other minority religions. But today, a U.S. coalition has eliminated the Islamic State’s chokehold on much of northern Iraq, including the city of Mosul.

Nov. 7, 2016: The Marza family were among 226 Assyrian Christians taken captive by the Islamic State group in a February 2015 attack on their villages in Syrias Khabur River valley. It took a year to free the hostages, and only after three were killed and millions of dollars gathered by the Assyrian diaspora worldwide was paid to the militants, and in the end the Khabur region has been totally emptied of the tiny, centuries-old minority community. (AP Photo/Michael Probst)

Prospects for Christianity surviving in Iraq now turns on whether the Chaldean, Syriac and Assyrian believers will be allowed to return to their ancestral homelands.

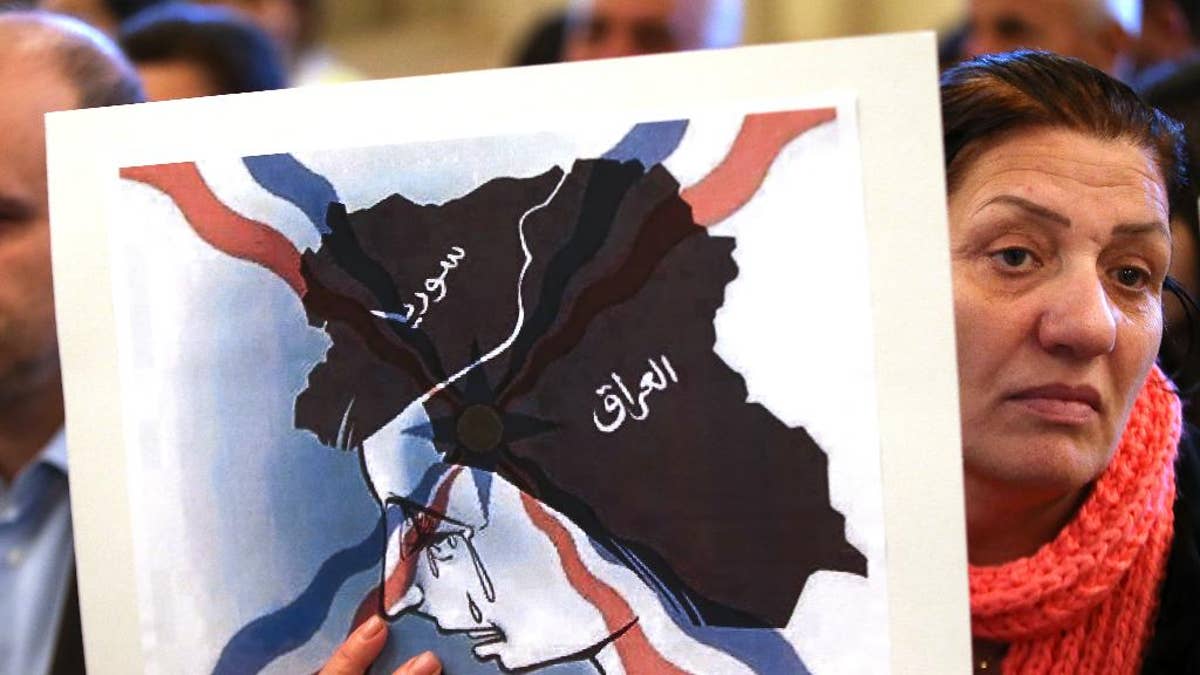

Thursday, Feb. 26, 2015: An Iraqi Assyrian woman who fled from Mosul to Lebanon holds a placard depicting the map of Iraq and Syria, during a sit-in for abducted Christians in Syria and Iraq, at a church in Sabtiyesh area east Beirut, Lebanon. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A majority of the Assyrian towns in the Plain have been left decimated. In some of the towns most of the infrastructure has been reduced to rubble; in others, dangerous chemical compounds have been dumped, polluting the ground to toxic levels.

“Everything is damaged,” Jalal, an Assyrian from the village of Karamles, told Fox News in December 2016. “Houses have been burned by fire. There’s no water, no anything. People will only return if there is some sort of promise of protection.”

Residents carry the body of several people killed during fights between Iraq security forces and Islamic State on the western side of Mosul, Iraq, Friday, March 24, 2017. Residents of the Iraqi city's neighborhood known as Mosul Jidideh at the scene say that scores of residents are believed to have been killed by airstrikes that hit a cluster of homes in the area earlier this month (AP Photo/Felipe Dana) (Copyright 2017 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

One proposal that has been vetted is to create a safe zone for Christians, an area that could evolve into a semi-autonomous region such as the Kurds are seeking.

Some organizations are helping with efforts to rebuild Assyrian villages in the area. The Iraqi Christian Relief Council has been spearheading an initiative since last year called Operation Return to Nineveh, which is raising funds to rebuild homes, churches and infrastructure that was destroyed by ISIS.

“Restoring these villages will be a long-term project, but it has to be done,” Juliana Taimoorazy, the organization’s executive director, told Fox News in December. “It’s doable only if there’s active security on the ground.”

But such efforts are the exception, not the rule.

“Not nearly enough is being done for Iraqi Christians who want to return home. ISIS has been pushed back and trickles of IDPs [internally displaced persons] have begun returning to their towns and villages, but no one is making any special effort to help them,” says Robert Nicholson, executive director of the Philos Project, a U.S.-based advocacy group for Christians in the Middle East said to Fox News.

“They need massive reconstruction, jobs, schools, and affirmative protections for their religion, language, and culture. Most importantly, they need to be empowered to protect and govern themselves so that this kind of genocidal destruction won’t happen again.”

Some groups favor a go-slow approach to bringing Christians back to northern Iraq.

“It’s a little early to jump to safe havens,” David Curry, CEO of Open Doors USA, which monitors incidents of Christian persecution worldwide, tells Fox News. “They often wind up creating a bigger target.”

No matter if or how quickly Christians are able to return home, persecution of believers will remain a fact of life.

“It is hard to predict how many Christians will be killed this year, but it seems likely that they will remain the No. 1 target of religious persecution,” Nicholson told Fox News. “Believing that a man named Jesus Christ was crucified and rose again for the sins of the world is still one of the most dangerous things one can do in many parts of the world.”

Syria. For a majority of the last century, this country has had a relatively sizable Christian presence, comprising at least 10% of the total population.

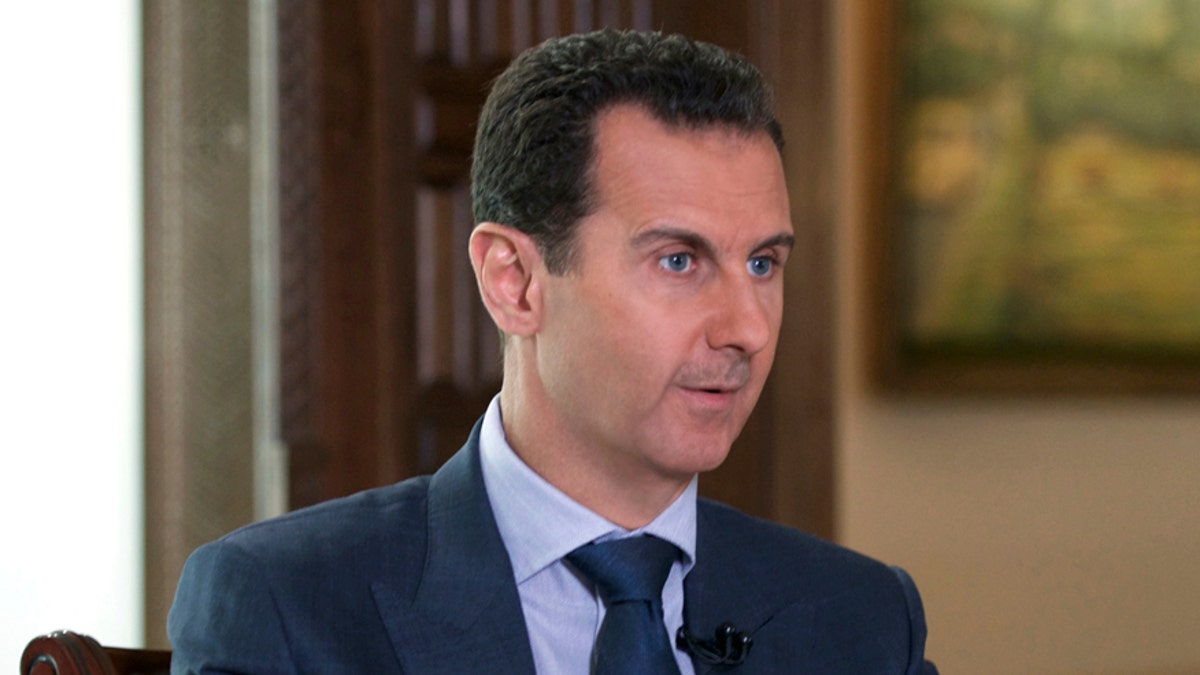

Many of Syria’s Christians, known as Eastern Orthodox, have historically seen their country as an oasis of religious freedom when compared to neighboring countries. President Bashar Assad’s regime, which is predominantly Alawite, a variant of Shia Islam, has long allowed churches to evangelize, publish religious materials and build sanctuaries. The Christian population has also had access to education and employment and many are more financially well off then their Muslim counterparts.

However, things may be growing worse for the Syrian church. As the civil war continues, believers in the country have been split over whether to support the Bashar regime. Some support the regime but also believe that all Syrians have rights that should be afforded to them. Some Christians have become part of the diaspora as well, but it is for a myriad of reasons other than Muslim persecution.

FILE -- In this Sept. 21, 2016 file photo released by the Syrian Presidency, Syrian President Bashar Assad speaks to The Associated Press at the presidential palace in Damascus, Syria. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillersons statement Tuesday, April 11, 2017, that the reign of President Bashar Assads family is coming to an end suggests Washington is taking a much more aggressive approach about the Syrian leader. Taking him out of the equation without a clear transition plan would be a major gamble. (Syrian Presidency via AP, File)

While many Syrian Christians do not want to become refugees, there is an underlying fear among the community that their country could have the same issues seen in Iraq if the regime is toppled.

Prospects for Syrian Christians will turn on whether the Assad regime survives and, if it does not, whether a successor government maintains the current regime’s protection of the church.