Troops began mobilizing at around 7 a.m. on September 11, 1973 in the Chilean port city of Valparaíso — the birthplace of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Two hours later, government military soldiers controlled the country, with exception of the presidential palace of La Moneda in downtown Santiago.

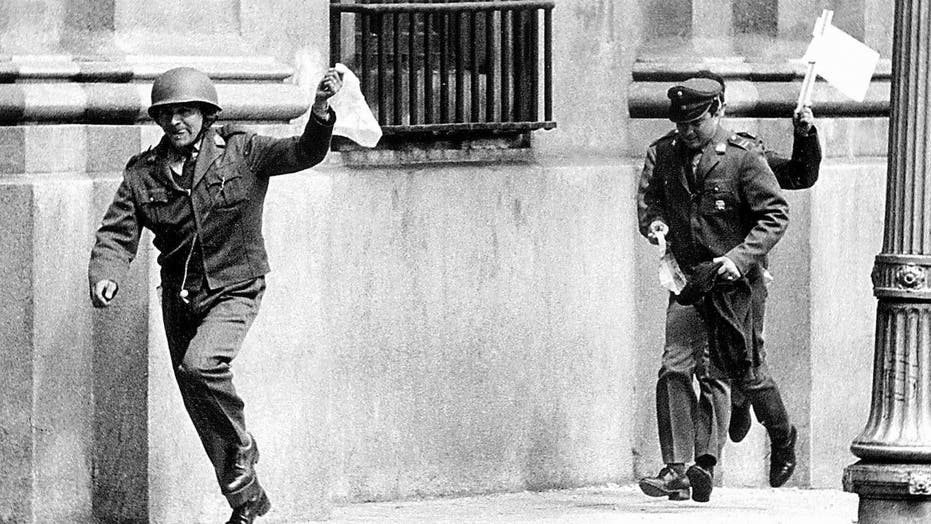

Salvador Allende – the democratically-elected, socialist president – refused to surrender, but as Air Force Hawker Hunter jets bombed the residence and military forces stormed the building, Allende took his own life and by 2:30 p.m., the Chilean military was in control of the Andean nation.

The CIA-backed coup took less than eight hours, but its impact is still palpable in this South American nation 40 years ago. Political and civil rights were suspended; the press was censored; alleged dissidents were interrogated and tortured. In all, almost 4,000 people were killed under Pinochet’s rule, which lasted until 1990, and the coup set the precedent for military juntas in neighboring Argentina and Uruguay.

While the Chilean coup had a profound impact on the political system in terms of reforms in the intelligence community and ruling out assassinations, in many ways we have not learned any lessons from the past.

- Cynthia J. Arnson, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

The coup was immortalized for the American public in the 1982 movie "Missing," starring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek.

As a democratic Chile commemorates the 40th anniversary of its own 9/11 on Wednesday, the country is still coping with the scars and memories from the Pinochet dictatorship as it moves through the growing pains of surfacing from a long era of repression.

“Although it wasn’t the bloodiest coup, it left a huge imprint on Latin America,” Larry Birns, executive director of the Washington D.C.-based think tank, Council of Hemispheric Affairs told Fox News Latino.

Birns, who was in Santiago on the day of the coup while working for the United Nations, recalled the chaos of the military-seized power and the imprint the coup made on the region’s political and psychological landscape.

The Argentinean military junta, the brutal Uruguayan military dictatorship and the joint campaign of political repression and terror by Latin American nations, in many cases with U.S. government backing, all followed in the footsteps of the Chilean coup.

Chile’s robust economy, its current distrust of the military and several measures implemented by former president Michelle Bachelet — and current presidential frontrunner — to remember and investigate the dictatorship are also by-products of the coup.

Bachelet, who was detained and exiled during the military dictatorship, has called for a full investigation on the human rights abuses committed during Pinochet's rule. She has also downplayed the accusations that during Allende’s time in office, Chile was on the verge of civil war.

"It is fair to say there was a lack of dialogue and a polarization of the politics then,” she said, according to the BBC. “But it is unfair to say that the military coup was inevitable."

The first decade after Chile returned to democracy, its citizens appeared hesitant to push their newfound freedom. But now, as time goes by and Chile’s democratic institutions have gained strong footing, Chileans are beginning to exercise their rights.

Prosecutions of former junta leaders continue, while indigenous groups, environmentalists and still take to the streets to protest a number of issues — something unheard of during the Pinochet era.

"Forty years after, [Allende] is mentioned more than ever by the young people who flood the streets asking for free, quality education," said Salvador Allene’s daughter, renowned author and Sen. Isabel Allende, according to the Associated Press. "Allende's profile keeps on growing while Pinochet is discredited."

While Chile has recovered from the dictatorship to become one of Latin America’s leading political and economic powers, the United States — particularly the CIA — is still recuperating from its involvement in the 1973 coup.

From propaganda and covert action during Allende’s time in office to knowledge of the coup plot and the Operation Condor, the CIA was deeply involved in the overthrow of the government and the installation of Pinochet's dictatorship.

“[The] CIA sought to instigate a coup to prevent Allende from taking office after he won a plurality in the 4 September [1970] election,” the CIA general report on the coup stated.

The CIA turned down a Fox News Latino request to comment on the clandestine service’s involvement in the coup, but many analysts cite the Cold War mentality in the U.S. at the time — and Allende’s friendly relations with Cuba’s Fidel Castro and the Soviet Union — as the prime reason for CIA's direct involvement in Chile.

“The Cold War provided the justification to do these things that were flagrant offenses to U.S. values and laws,” Cynthia J. Arnson, the director of the Latin American program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told Fox News Latino.

“While the Chilean coup had a profound impact on the political system in terms of reforms in the intelligence community and ruling out assassinations, in many ways we have not learned any lessons from the past,” Arnson said.

Despite tensions over the U.S. role in the coup, relations between Washington and Santiago have remained stable and the two nations remain strong political and economic allies.

“Chileans have created a strong and thriving democracy over the last 25 years that is recognized as a regional leader in supporting democratic principles, human rights, rule of law, and basic freedoms,” Gabrielle Guimond, the press attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, said in an email to Fox News Latino

“The United States has declassified and released to the public extensive documentation related to events in Chile before, during, and after the events of September 11, 1973,” Guimond wrote.

As more information is revealed and those guilty of crimes finally are having their day in court, the scars of Chile’s “Dirty War” are finally beginning to heal and many Chileans say they feel more empowered to speak up.

"It's a return to the energy lived during Allende's time,” Patricio Fernandez, editor of Chile's most widely read weekly magazine, The Clinic, told the Associated Press.