KABUL, Afghanistan – In the basement of the old Mullah Shams market on Kabul's famous Chicken Street, below the beggars, the gemstone carvers, street artists and carpet stores, lies a tiny windowless store stuffed to the ceiling with troves of ancient weapons and slices of Afghan history.

Stepping into the store of 69-year-old Tawakal is like entering a time machine. For decades, Tawakal has collected and restored weapons dating back hundreds of years from provinces across the country, estimating that he has almost 200 tucked into his store, known simply as the Tawakal store, and a storage room in the back.

"We have guns, knives, swords. Everything is historical," the barefoot, toothless smiling firearms expert enthused to Fox News.

Almost every piece has its own intricate insignia, from delicately carved calligraphy in the metal to the famous Afghanistan salpah stone ground into the wood carving. The weapons are all too old to be functional, instead serving as classic decor that he often lends to exhibits across the country.

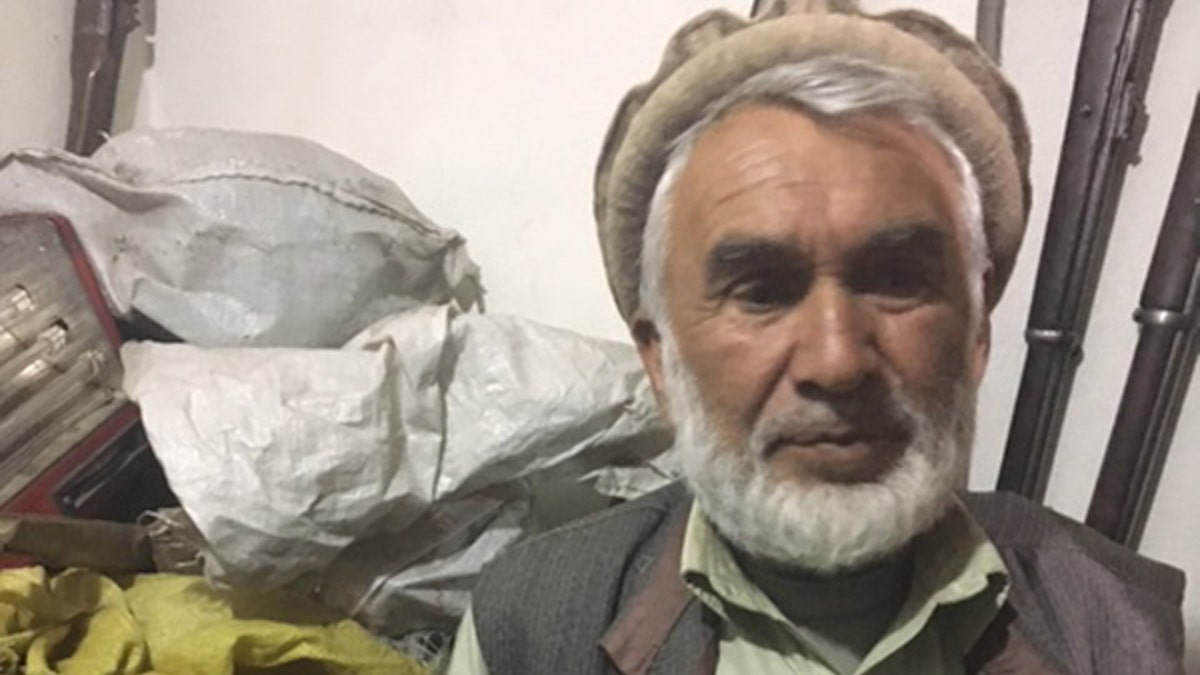

Tawakal in his shop (Hollie McKay/Fox News)

Tawakal says his favorite is a handmade "Chaq maki," or flintlock in English, that dates back hundreds of years. He offers the homemade muzzle-loading antique for $1,000, but is confident that if he was ever able to export the gun outside the country he could sell it for 10 times that amount.

"Before this gun, Afghans had to fight by the sword," he says, speaking Farsi, Afghanistan's official language. "This was the first. This is what was used to push back the British Army."

The weapon, known as a flintlock Jezail, still has the original barrel and ram rod, with newer additions of mother-of-pearl and lock.

Next, Tawakal shows off a British-made 1863 Tower rifle -- which he offers at $400 -- cradling it around the store as if it were a small child. The rifle was made for artillery gunners.

Then there is a 1860 Enfield priced at $100, an antique Belgian-made Martini Muscat and an antique Martini-Henry. The barrels of the official pattern Martini-Henry, first used by the British Army in 1871, are much longer. The one Tawakal has appears to have been cut back, likely to make it easier to handle.

"After the British came, their guns became very popular here," he explained, referring to the three wars Afghanistan and British forces fought in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Tawakal also displayed a Safavid gun -- one of the smallest in his collection -- and, in his words, "with a story that goes back a long, long time."

"This was used by the Safavid army when they had no other gun for fighting," Tawakal said of the military force that ranged across Persia in the 18th century.

Tawakal also proudly points to a "Sachma" gun, which he sells for $250, re-enacting how the soldiers who first used the weapon would have filled the muzzle with gunpowder, or “barood” in Urdu, and lit a match to shoot out the "sachmah," or lead ball, as the projectile.

Also among Tawakal's weapons cache, wrapped in a blue scarf and hidden in the storage area, is the Afghan-made "Sorbi Yak Taka," meaning one-shot rifle. It appears to be an Afghan knockoff of a British Martini-Henry rifle. These single-shot, breech-loading rifles were the mainstay of the British Empire throughout the world during the 1800s, when cartridge arms replaced muzzle loaders.

Tawakal says it was used by the Amanullah army some 100 years ago and comes with a matching sword. It's a package deal, he says, at $600.

The store also features a GR Tower flintlock that looks to be made of some original parts and some new parts from an Afghan government Martine Henry and an Afghan Le Mothield Bayonet.

Equally as vast as his gun collection is the assortment of swords that adorn the walls and cabinets. The eldest were hand-crafted and used three centuries ago by the Mughals, Safavid and Changez armies.

One is an Afghan tulwar or Pushtun short sword. It bears similarities to other ancient weapons like the Roman gladius. The handle has a weight in the rear to balance the weapon and make it handier for slicing. The store also boasts straps -- made from "cow and camel skin" -- complete with tiny pouches to carry stones and fuel to clean their weapons, little tools like hammers and tubes for measuring the gunpowder they needed to fire away.

And just for good measure, a few slightly stained, large-size Soviet winter hats, made in 1985, worn by their commanders during the bloody war that ravaged their land for thirteen years, are hanging high. The once soft wool has roughened through the passage of time and, according to the store owner, people only really buy them for exhibition purposes.

"No one really wears them," he explains.

Eight years ago Tawakal -- who previously sold antique weapons privately -- opened the little shop to appeal to foreigners at the height of Operation Enduring Freedom. But these days, sales have slowed to a crawl. He spends much of his day drinking tea and tweaking his many treasures.

"Nobody comes to Kabul anymore because of all the explosions," he laments. "I used to love it when people from all over the world came in here."

Tawakal notes that while some weapons are originals, others are only partly original, while some he is unable to guarantee their authenticity beyond his own summations.

Guns are a way of life for Afghans. Almost every night, gunshots ring out -- celebratory or otherwise -- and when people talk, the talk is almost of war and the weapons they once used or the ones they want or need.

"I know everything there is to know about guns," Tawakal added. "I have known guns all my life. This is my life, my work."