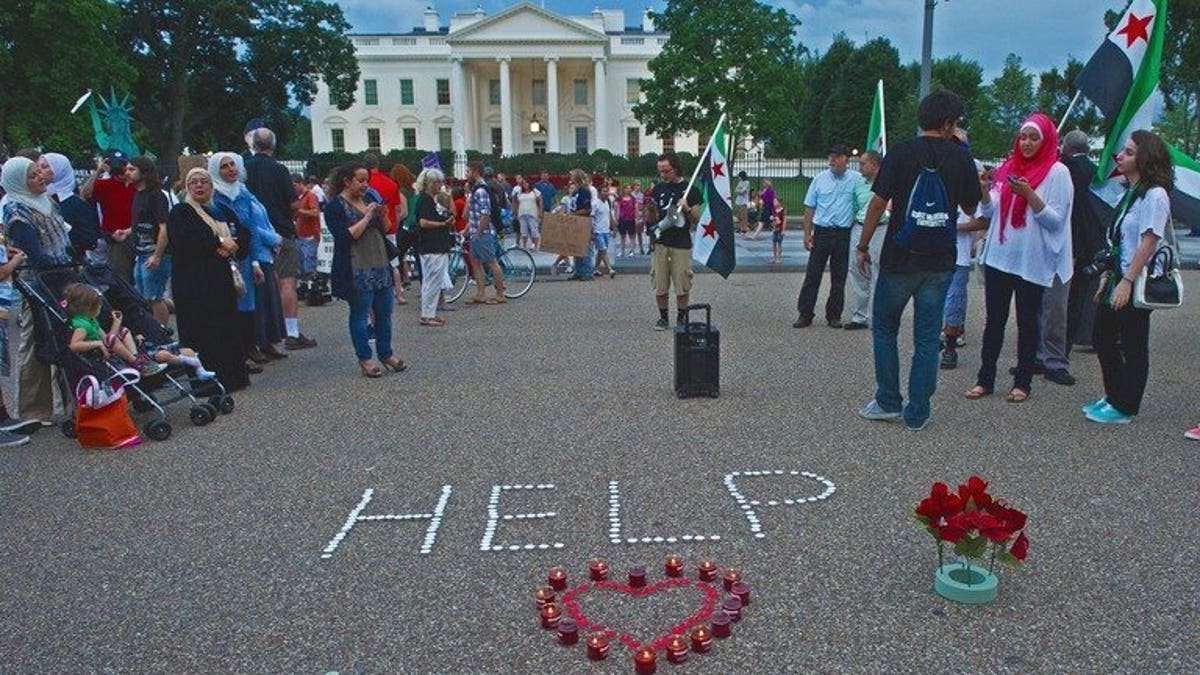

Demonstrators calling for help from US President Obama on the Syrian revolution protest in front of the White House on August 21, 2013, in Washington, DC. A year after Washington said using chemical weapons would cross a "red line," the alleged gas attack outside Damascus has exposed how few options the West has to try to end Syria's violence. (AFP/File)

PARIS (AFP) – A year after Washington said using chemical weapons would cross a "red line," the alleged gas attack outside Damascus has exposed how few options the West has to try to end Syria's violence.

Diplomatic sources say the shocking images of the alleged victims of the attack, which the Syrian opposition claims killed more than 1,300 people in rebel-held towns east of Damascus, leave little doubt about the use of chemical weapons.

President Bashar al-Assad's regime has vehemently denied it unleashed chemical weapons and Russia, the regime's key international ally, has denounced the opposition claims as a "premeditated provocation."

But French President Francois Hollande, in talks with UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, denounced the "likely use of chemical weapons" in the attack, as Syria came under intense pressure to allow UN inspectors access to the site.

And several top Western officials, including French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius, have already compared the assault to the infamous 1988 gas attack by Saddam Hussein's regime against Iraq's Kurdish town of Halabja, which killed some 5,000 people.

Fabius said Thursday that if the massacre is confirmed, there should be a reaction "with force," though he ruled out the use of ground troops.

Sources among French authorities said possible military options were already well-known: arms deliveries to Syrian rebel fighters; the establishment of a no-fly zone; and targeted air strikes.

"If there is a military option, it will be the minimum," a French military source said.

"The only question is: What do the politicians and the international community want? There are scenarios among Western general staffs, but no real option has yet been settled on," the source said.

Military and diplomatic sources said nothing can be done without the involvement of Washington, which has so far been cautious in reacting to the reports, despite President Barack Obama's promise last year that the use of chemical weapons would be a "red line."

"I'm not talking about red lines. I'm not having a debate or conversation about red lines ... I'm not setting red lines," State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said when asked about the reports.

"We've seen from President Obama's attitude to the Syrian conflict that he and his military are extremely reluctant to be drawn into any kind of military activity in Syria," Jeremy Greenstock, the former British ambassador to the United Nations, told BBC radio.

Paul Freiherr von Maltzahn, of the German Council on Foreign Relations, said Western military action in Syria was currently "unimaginable."

"What could we expect? This will not stop the conflict, the war will continue," he said, adding that the focus for now should be on ensuring UN inspectors can investigate.

Lord Mark Malloch Brown, the former UN deputy secretary general, agreed, saying a diplomatic solution was still possible.

"We need to bring the rhetoric down from red line and military intervention to try and find common ground that we can agree on with the Russians and the Chinese, which is: Let's establish the facts," he told BBC radio.

"But at the moment this is already morphing into 'what next?' And that of course immediately raises the hackles of the West's opponents on the Security Council, risking therefore an inspection. And without an inspection it's going to be a series of charges and counter-charges from the different sides."

Analysts said that if the United Nations fails to obtain access for its chemical weapons inspectors in Syria -- headed by Ake Sellstrom of Sweden -- the international community will have lost all credibility on the question.

"After two-and-a-half years of conflict, not a single serious measure has been taken, what we are seeing is the total abandonment of a people that is being massacred," said Ziad Majed, a professor at the American University of Paris.

"If the Sellstrom mission does not react, they will no longer have any credibility."