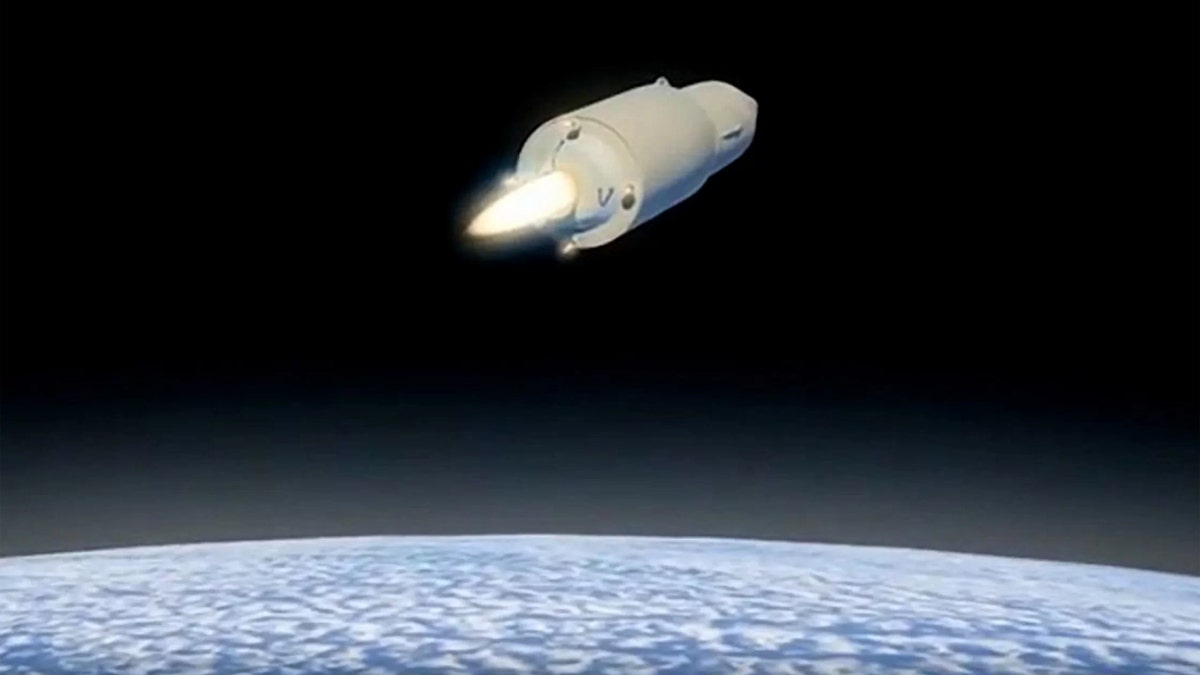

During a speech to lawmakers, Russian President Vladimir Putin showed images of a hypersonic weapon dubbed Avangard that can apparently reach Mach 20. Credit: Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation

Warnings of a Russian hypersonic weapon that the U.S. can't defend against may have had you running for the bomb shelter last week. But what, exactly, is this weapon, and how does it work?

Russian President Vladimir Putin first announced the hypersonic weapon, code-named Avangard, in a speech in March. Last week, U.S. intelligence sources told CNBC that the weapon had been successfully tested a number of times and could be operational by 2020.

The Russians have released few concrete details about the weapon, but from the information available, it appears the weapon is a so-called hypersonic glide vehicle, said Thomas Juliano, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Notre Dame who specializes in hypersonic flight.

Putin has claimed that the vehicle is capable of reaching speeds of Mach 20 — or 20 times the speed of sound — and could evade current U.S. missile defense systems. Worryingly, the vehicle can supposedly carry a nuclear warhead, according to the intelligence sources. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

Rather than generating its own power to reach hypersonic speeds, the glide vehicle catches a ride atop an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Typically, these rockets fly to space on an arcing trajectory before releasing warheads near the top of the parabola, and these warheads drop back down onto the target at hypersonic speeds under the power of gravity.

Rather than falling back to Earth, though, Avangard reenters the atmosphere at an angle and its aerodynamic shape generates lift that lets it glide down at hypersonic speeds, says Juliano, which allows it to travel further farther and maneuver as it descends.

Hyper engineering

The vehicle appears to follow a design known as a "waverider," Juliano said. Waveriders are hypersonic aircraft that have wedge-shaped fuselages specially designed to generate lift by surfing on the shock wave generated as its own aircraft punches through the air at a high speed.

This is important at higher altitudes, where air density is low, making it difficult to generate lift with conventional wing designs. And because it doesn't need large wings, the vehicle is more streamlined, and the reduced drag allows it to maintain its speed over a much longer distance, Juliano said.

Building a vehicle that can tolerate hypersonic speeds and the temperatures they generate is no easy feat, Juliano said. But the design the Russians have opted for circumvents one of the major challenges: propulsion. [Photos: Hypersonic Jet Could Fly 10 Times the Speed of Sound]

"Designing a successful propulsion system at Mach 10 or above is extraordinarily challenging," he said. "By putting the glider on top of an ICBM, you avoid the need to design a successful hypersonic air-breathing engine."

Controlling a vehicle at such high speeds is still incredibly tricky, though.The Russians claim that Avangard is highly maneuverable, and based on computer-generated video included in Putin's address, it appears to have several flaps similar to the aerofoils used by planes to change direction.

Adjusting the aerofoils at hypersonic speeds is not a trivial task, because the shock wave can have complex interactions with the air flowing over the vehicle's surfaces, resulting in "nonlinear" behavior, Juliano said.

That means tiny adjustments can have outsize impacts, which makes it very tricky to calculate how much to move a flap or aerofoil. "It has to be precise, it has to operate quickly and it's a much harder environment to predict," he said.

Nonetheless, Juliano thinks the Russian claims are credible, as the technology has been in development for some time. The U.S. tested its own version, dubbed Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2, in 2010 and 2011, but both flights were failures. And China also has an experimental system, code-named DF-ZF.

What is it for?

Russian efforts to develop hypersonic glide vehicles are explicitly aimed at evading U.S. missile defense systems, said Pavel Podvig, an independent analyst who specializes in Russia's nuclear arsenal. [Could the US Stop Nuclear Weapons?]

Current U.S. defenses are designed to take out conventional warheads from ICBMs on predictable ballistic trajectories while they are still in space; these defenses are not well suited to intercept weapons coming in on a high-speed glide in the atmosphere, Podvig said. And unlike traditional warheads, the vehicles will be capable of maneuvering around defenses.

But Podvig said it's not clear if the weapons really provide useful additional military capabilities. "It has been described as a weapon in search of a mission," he told Live Science. "My take is, you don't really need this kind of capability. It doesn't really change much in terms of ability to hit targets."

Podvig pointed out that the ICBM that carried the Avangard during testing, the SS-19, normally carries six conventional warheads. If the goal is to counter missile defense systems, it would be just as easy to overwhelm them with a greater number of standard warheads, he said.

But such weapons could breed dangerous uncertainty, Podvig said, because they aren't covered by arms-control treaties such as New START, which require countries to report the number, type and location of nuclear-capable weapons like ICBMs. In addition, the capabilities and potential uses of hypersonic gliders are still unclear.

"These systemscreate greater risks of miscalculation," Podvig said, "and it's not clear if we can effectively deal with those risks."

In an effort to reduce some of that uncertainty, the Pentagon is reportedly considering fielding space-based sensors to spot hypersonic weapons, according to Space News. The approach would require a costly constellation of satellites, but would be better at spotting weapons gliding in the upper atmosphere and could also see farther than land-based systems limited by the horizon.

Podvig says a properly designed system of this kind should be able to detect hypersonic weapons in flight, but it's not clear this would make it any easier to intercept such fast and maneuverable vehicles.

Originally published on Live Science.