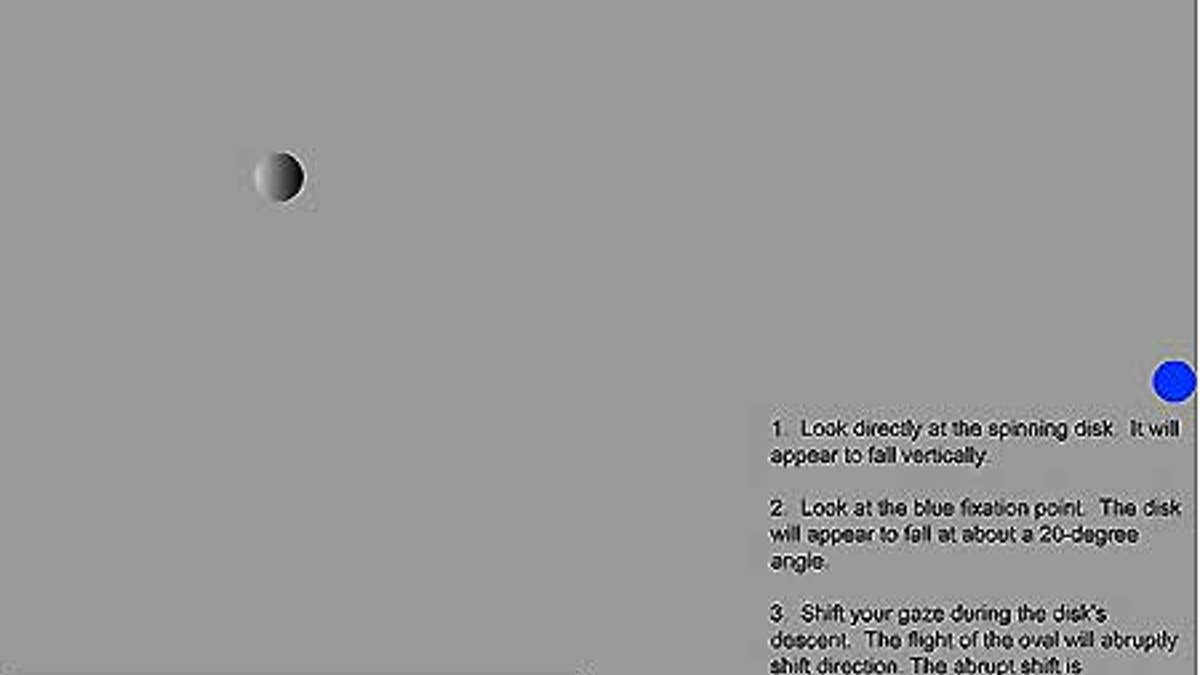

The secret of the curve ball, chosen as the world's best illusion, is shown in this still shot. (ISNS)

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The three best visual illusions in the world were chosen at a gathering last weekend of neuroscientists and psychologists at the Naples Philharmonic Center for the Arts in Florida.

The winning entry, from a Bucknell University professor, may help explain why curve balls in baseball are so tricky to hit.

A properly thrown curve ball spins in a way that makes the air on one side move faster than on the other. This causes the ball to move along a gradual curve. From the point of view of a batter standing on home plate, though, curve balls seem to "break," or move suddenly in a new direction.

Click here to see the illusions in action.

This year's winning illusion, created by Arthur Shapiro of Bucknell University in Pennsylvania, may explain this phenomena. His animation shows a spinning ball that, when watched directly, moves in a straight line. When seen out of the corner of the eye, however, the spin of the ball fools the brain into thinking that the ball is curving.

So as a baseball flies towards home plate, the moment when it passes from central to peripheral vision could exaggerate the movement of the ball, causing its gradual curve to be seen as a sudden jerk.

In second place was an illusion of ghostly colors. Stare at a waterfall for a few minutes, look away, and the still world around you will appear to flow. The effect is called an "afterimage."

Scientists in Israel created a drawing of a sky with clouds that flashes red for a split second. A white dove flying across the sky seems to turn red seconds after the flash, showing that an afterimage color can linger in our vision and bleed into empty spaces.

The third place award went to a pair of photographs. One appears to be male; the other, female. Both faces actually belong to the same person, digitally altered by Richard Russell of Harvard University. The dark parts of the photograph are a little darker and light parts are a little lighter in the "female" photograph. The subtle changes suggest that one way our brains may sort out sex is to notice how strong the contrast is between features.

"Visual illusions show us where physical reality and our perceptions don't match, so we can get at what the brain is actually doing," says contest organizer Stephen MacKnik of the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix.

Shapiro's trophy, a sculpture created by Italian artist Guido Moretti, is itself a visual illusion that changes shape depending on what angle it is viewed from.

This story was provided by the Inside Science News Service.