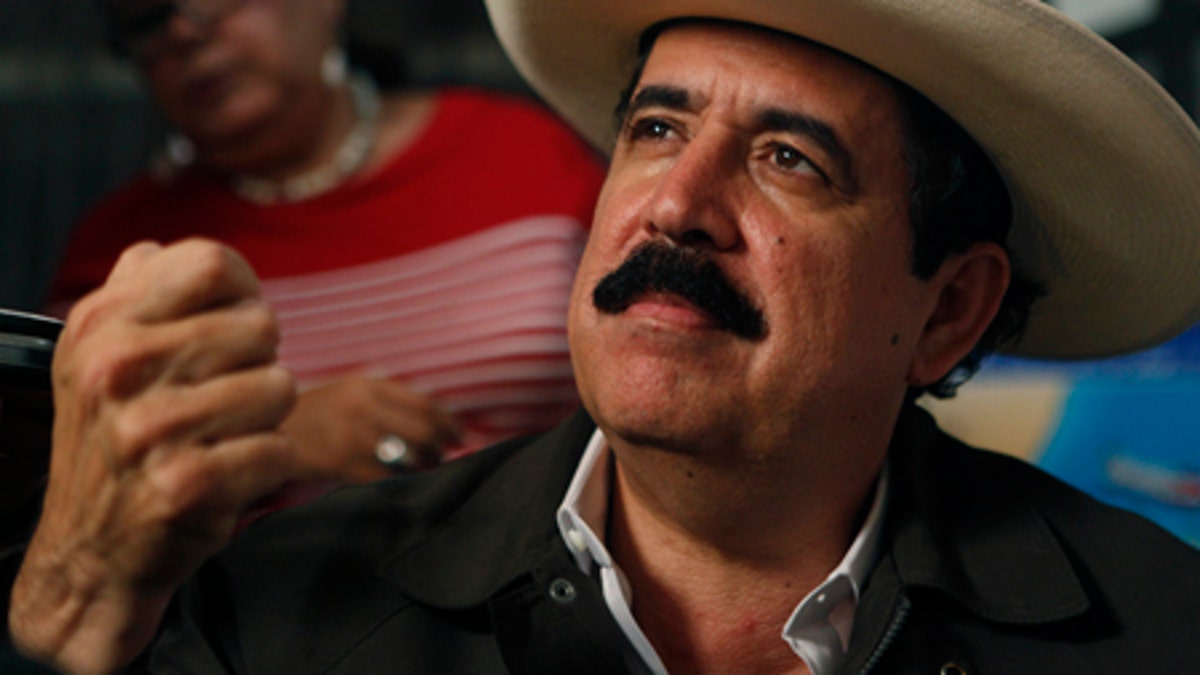

July 17, 2009: Honduras' ousted President Manuel Zelaya answers questions during a news conference in Managua. (AP)

ESTELI, Nicaragua – Honduras' deposed president set up base near his country's border to prepare a return home, urging soldiers to ignore an arrest order against him and shrugging off warnings that his homecoming could provoke violence.

Manuel Zelaya drove a jeep to Esteli, a town just 25 miles (40 kilometers) south of the Honduran border, where he shut himself inside a hotel Thursday night to plan a strategy for reclaiming the presidency from the interim government that sent him into exile.

He said he would make a second bid to return home as early as Saturday, saying U.S.-backed mediation efforts had broken down. The interim government vows to arrest the president if he sets foot in Honduras, and imposed a 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew along border areas.

The 56-year-old ousted leader, wearing his trademark white cowboy hat, was accompanied by the foreign minister of Venezuela, whose leftist President Hugo Chavez has been the most vociferous critic of the June 28 coup.

Zelaya said he would spend Friday studying how best to enter Honduras — whether by land, sea or air. He urged Hondurans to gather wherever he decides to cross and called on soldiers to stand down when they see him.

"I am on my way to Honduras, and I hope most Hondurans can overcome the checkpoints, that they head to the border, and that they not fear the soldiers," Zelaya said at new conference at the hotel. "I am strong, I do not fear, but I know that I am in danger."

He addressed the Honduran military: "Don't aim your rifles at the representative of the people or at the people."

All governments in the Western Hemisphere have condemned the coup, in which soldiers acting on orders from Congress and the Supreme Court arrested Zelaya and flew him into exile. Nations on both sides of the political spectrum say Zelaya's return to power is crucial to the region's stability.

Zelaya said the mediation efforts, led by Costa Rican President Oscar Arias, failed after representatives of the interim government flatly rejected the possibility that he might return to finish his presidential term, which ends in January 2010. They say they cannot overturn a Supreme Court ruling forbidding Zelaya's reinstatement.

But Jose Miguel Insulza, secretary-general of the Organization of American States, held out hope that the two sides might still reach a settlement — and called Zelaya's attempt to return without an agreement "hasty."

"He has always wanted to return to his country, but it's important to make an effort to avoid a likely confrontation," Insulza said.

He said that neither delegation had officially responded to Arias' proposal, which calls for Zelaya's reinstatement, amnesty for the coup leaders and early elections.

The U.S. warned of tough sanctions against Honduras if Zelaya is not reinstated, but also said Thursday it does not support Zelaya's plan to return on his own.

"Any step that would add to the risk of violence in Honduras or in the area, we think would be unwise," State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley said in Washington.

The Honduran military thwarted Zelaya's first attempt to return home July 5 by blocking the runway at the airport in the capital, Tegucigalpa. The flight sparked clashes between Zelaya's supporters and security forces in which at least one protester was killed.

Lorena Calix, a spokeswoman for Honduras' national police, said officers were ready to detain Zelaya if he tries again to come home.

The Honduran military said it would not be responsible for Zelaya's security if he returns, responding to the ousted president's warning earlier this week that he would blame military chief Gen. Romeo Vasquez "if something happens to me on route to Honduras."

The Defense Ministry suggested Zelaya might stage an assassination attempt on himself to blame Vasquez.

"We cannot be responsible for the security of people who, to foment general violence in the country, are capable of having their own sympathizers attack them," the ministry said in a statement late Thursday.

Honduras' Supreme Court ordered Zelaya's arrest before the June 28 coup, ruling his effort to hold a referendum on whether to form a constitutional assembly was illegal. The military decided to send Zelaya into exile instead — a move that military lawyers themselves have called illegal but necessary.

Zelaya's opponents, who objected to his populist and socialist policies, have argued the president was trying to change the constitution to extend his term. Zelaya denies that.