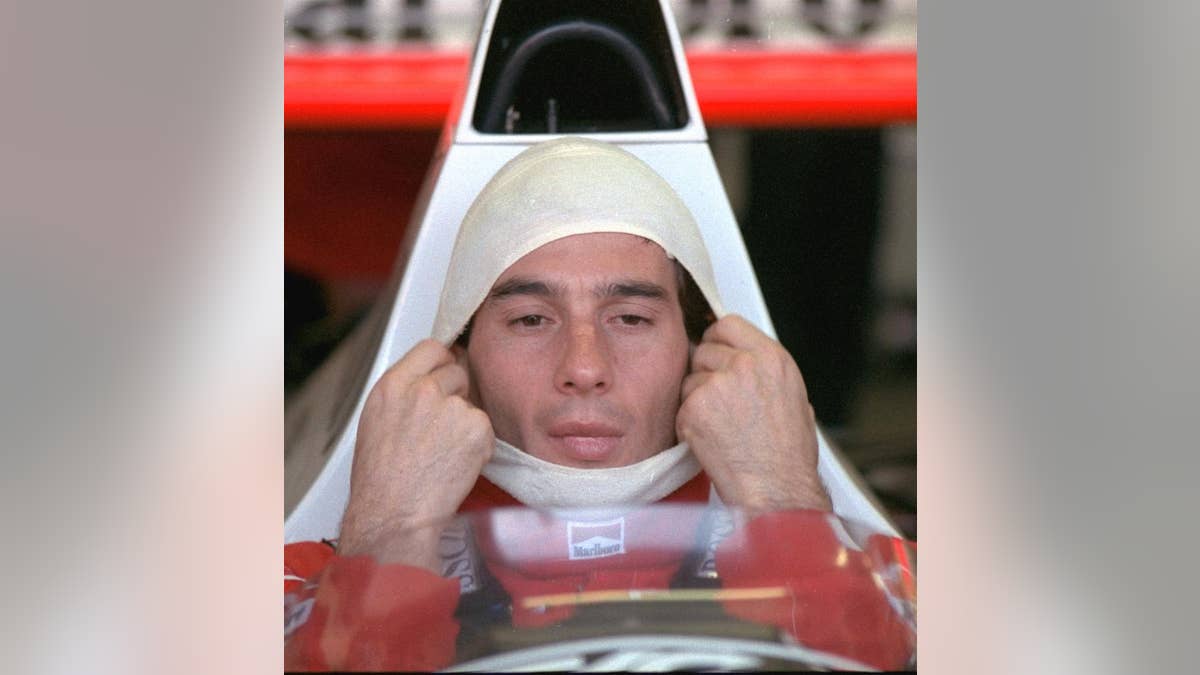

FILE - In this November 4, 1989, file photo, Brazilian driver Ayrton Senna, in a McLaren Honda, pulls on a fire resistant mask before going out to practice for the Australian Grand Prix. Senna won three Formula One titles — in 1988, 1990 and '91 — all with McLaren. He moved to the Williams team for his tragic 1994 season. Despite his career being cut short when he was 34, his 41 wins stand third all-time behind Michael Schumacher's 91 and rival Alain Prost's 51. He died at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. (AP Photo/Stephan Holland, File) (The Associated Press)

IMOLA, Italy – When Ayrton Senna crashed into a concrete wall during the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, a routine day of race coverage transformed into a marathon effort of wall-to-wall reporting for Associated Press writer Piero Valsecchi.

"I have to admit that I immediately understood it was going to be a heck of a day," the now-retired Valsecchi said ahead of Thursday's 20th anniversary of Senna's death. "It's egoistical to say but thoughts like those creep into your mind. And we had already had two tense days of accidents. It was an incredible sequence of events over those three days."

Another high-speed crash a day earlier had killed Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger. And during practice two days earlier, the car of Rubens Barrichello went airborne, crashed against the barriers and flipped. The young Brazilian sustained a concussion and amnesia and called his survival a miracle.

At the start of Sunday's race, another crash injured four spectators. But none of those accidents prompted the impact of Senna's crash.

"Inside the press center there was immediate reaction, not just because of the accident, but because it was Senna, the three-time world champion," Valsecchi said. "He was the best-known driver.

"He was also a driver who was always available to speak with the media. If you asked him something he always responded. He may not have been the nicest driver but he understood what you wanted and gave you the response you needed for your job."

After Senna was extracted from his car, he was transported to a hospital in nearby Bologna and declared dead four hours later.

"You could tell that he wasn't moving when he was taken out of the car," Valsecchi said. "But obviously you couldn't report that he was dead yet.

"First there was an announcement that he was being treated in Bologna for serious injuries, then the announcement of his death was given hours later, I think it was about 7 p.m., by the organizers and an official from the FIA," Valsecchi said. "At that hour, most people had already left the track — fans, other drivers and teams."

There was no movement by other drivers to cancel the race after the death of Ratzenberger, who was not well known and drove for a small team, Simtek Ford.

"No. The question was never raised," Valsecchi said. "These days, they probably would have canceled both qualifying and the race.

"Although I remember that after Ratzenberger's accident, Senna walked over to the site of the crash to take a look. So he was already a bit empty and saddened by what he saw. It seemed like he already had negative thoughts."

With no cellphone, Valsecchi's communications were limited to a single telephone line.

"I had a telephone on my desk but I only had one line, meaning I couldn't talk to my editors and file at the same time," he said. "The line was either connected to the phone or to the computer.

"And I still had to follow the rest of the race and report on who won. It was strange."

Indeed, the race continued after Senna's accident and was won by Michael Schumacher.

"From a journalist's point of view, a day like that cuts five years off of your life," Valsecchi said. "You just get trampled by a mountain of news and the way we work everything has to be done immediately."

In the pre-Internet age, and with limited communications, that was a steep challenge.

"While the newspapers could wait until 8 or 9 p.m. before starting to write — with teams of three or four people each — we had to provide the news in running style," Valsecchi said. "And being alone, it was difficult to find time to report — make calls or seek out sources — because there was so much that needed to be filed."

Valsecchi, 71, now lives with his wife Luisa in the northern Italian town of Casciago. He retired from the AP in 1997.