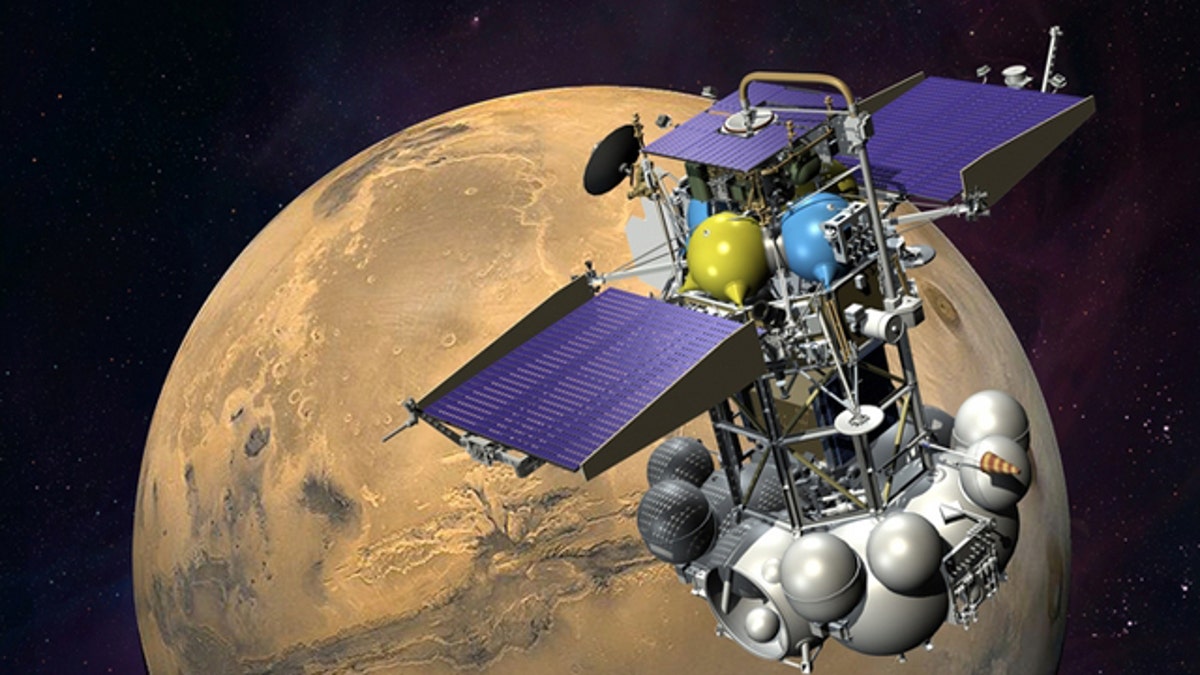

An artist's impression of Phobos-Grunt in Mars orbit. (ROSCOSMOS)

Scientists grew excited last week as Russia's planned its first interplanetary mission in 15 years. By now, the ambitious mission should be powering through space, toward the Martian moon Phobos.

Instead, Russia's space agency spent Friday discussing uncontrolled reentry scenarios.

Authorities may be looking for someone to blame after a lengthy string of mission failures. According to an Interfax bulletin, an anonymous source indicated that this may force reform in the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, and "a number of positions of responsible persons" could face jail time.

As if that news weren't bad enough, this could be an uncontrolled toxic reentry scenario.

Phobos-Grunt -- correctly written "Fobos-Grunt," meaning "Phobos-Soil" or "Phobos-Ground" -- is fully laden with unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide; that's ten tons of fuel and oxidizer. The probe itself weighs in at only three tons.

ANALYSIS: Time Running Short for Stranded Mars Probe

The majority of the fuel will likely vaporize during reentry, but everyone will be hoping for a splash-down in an ocean (which covers two-thirds of Earth, fortunately), as the wreckage will still be hazardous. There's also a small quantity of radioactive cobalt-57 in one of the science missions housed in the probe -- a fact that will most likely cause a media frenzy.

It is for these reasons that the Russian media is dubbing Phobos-Grunt "the most toxic falling satellite ever."

(At time of writing, there is no official word from the Russian space agency about the Phobos-Grunt situation.)

Though Russian mission controllers are frantically trying to regain control of the craft, it's not looking good. Friday's efforts are widely regarded as a last-ditch attempt to salvage the mission. Other space agencies such as NASA and ESA have offered to assist, but the probe is quickly becoming unrecoverable.

Since Phobos-Grunt was placed in low-Earth orbit (LEO) on Tuesday, and the probe successfully separated from its booster rocket, its attached cruise stage rocket has yet to light up, providing a critical two burns to blast the probe away from Earth to begin its planned 10-month journey to the Red Planet.

ANALYSIS: Russia's Mars Mission May Be In Trouble

It is unknown whether there's a software error or hardware glitch, but attempts to upload new commands to the onboard computers have so far failed to change the situation. Phobos-Grunt's batteries are draining and its orbit is degrading. It looks as if the probe will reenter later this month/early December. NORAD is reportedly putting a Nov. 26 reentry date on Phobos-Grunt.

And guess what? This will be the third large piece of space junk to reenter in an uncontrolled manner this year. In September, NASA's 6-ton UARS atmospheric satellite burned-up over the Pacific. In October, the German 2.4-ton ROSAT X-ray space mission reentered over the Bay of Bengal. Could November be the third consecutive reentry month?

Like UARS and ROSAT, the likely Phobos-Grunt reentry will be uncontrolled and at the mercy of a highly dynamic upper atmosphere. Also, the probe's orbit takes it between the latitudes 51.4 degrees North to 51.4 degrees South -- most of the world's population lives within that zone, and Phobos-Grunt could come down anywhere. Despite the fact that pieces of the probe will hit the ground, it is still extremely unlikely it will cause death and destruction, however.

NEWS: Russia Aims For Mars Moon

The demise of Phobos-Grunt will be a huge loss to the scientific community. Not only was the mission designed to land and scoop up some regolith (dust and rock) from Phobos' surface, returning it to Earth for analysis, it is also carrying a fascinating Planetary Society experiment called the Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, or "LIFE."

LIFE is composed of many different types of bacteria to small organisms that seem to tolerate the space environment pretty well. "Tardigrades" -- known as water bears -- were also a part of the payload.

Why send microscopic organisms to a Martian moon?

In an effort to understand how life appeared on Earth, the experiment would have put the hypothesis of "panspermia" to the test. Panspermia is a proposed mechanism by which life may "hop" from one planetary body to the next -- meteorites slamming into Mars, say, ejecting many tons of debris into space. Should any organisms be "hitching a ride" on the debris, could they (or at least their genetic information) survive the interplanetary journey, and atmospheric entry, to spawn life on another world?

Alas, the LIFE experiment has been cut short. The first Chinese Mars satellite, Yinghuo-1, was also hitching a ride and won't go any further than LEO either.

Perhaps it's about time to ask those tardigrades for a favor ...