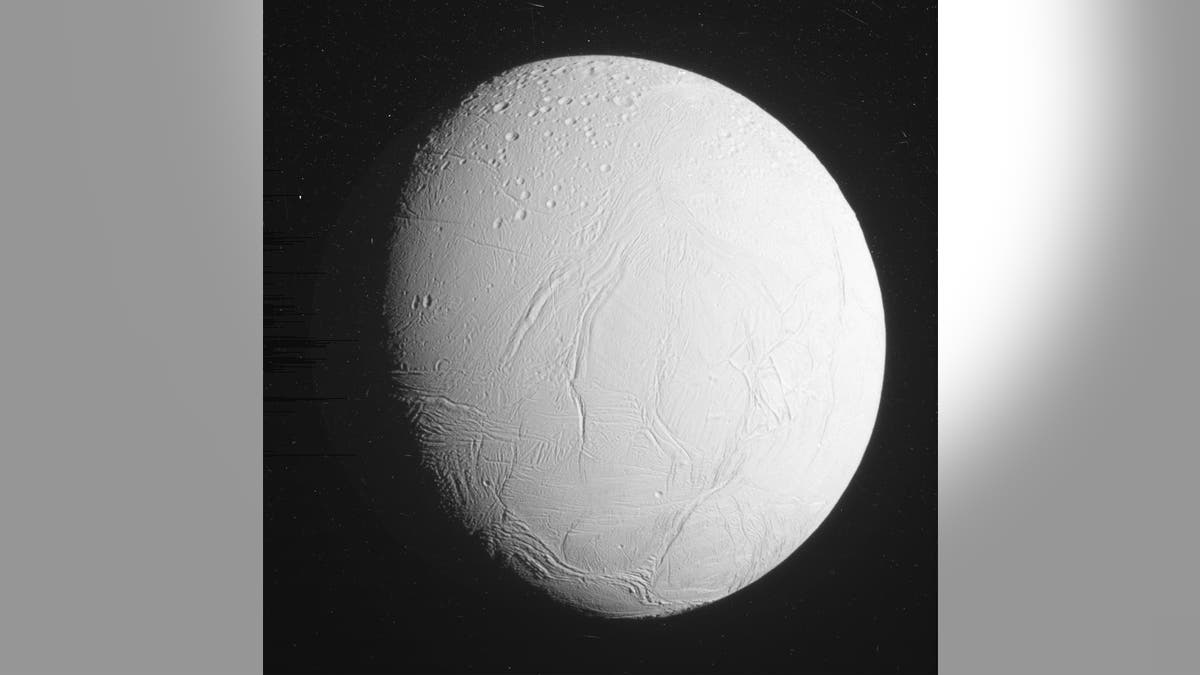

This unprocessed view of Saturn's moon Enceladus was acquired by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during a close flyby of the icy moon on Oct. 28, 2015. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

NASA has released the latest images of Saturn’s moon Enceladus taken by the Cassini spacecraft during its close flyby Wednesday, which suggest that this is one cold place.

The images were taken when the probe passed about 30 miles above the moon's south polar region. The spacecraft will continue transmitting data from the encounter for the next several days.

Related: NASA's Cassini spacecraft to make flyby of Saturn's moon Enceladus

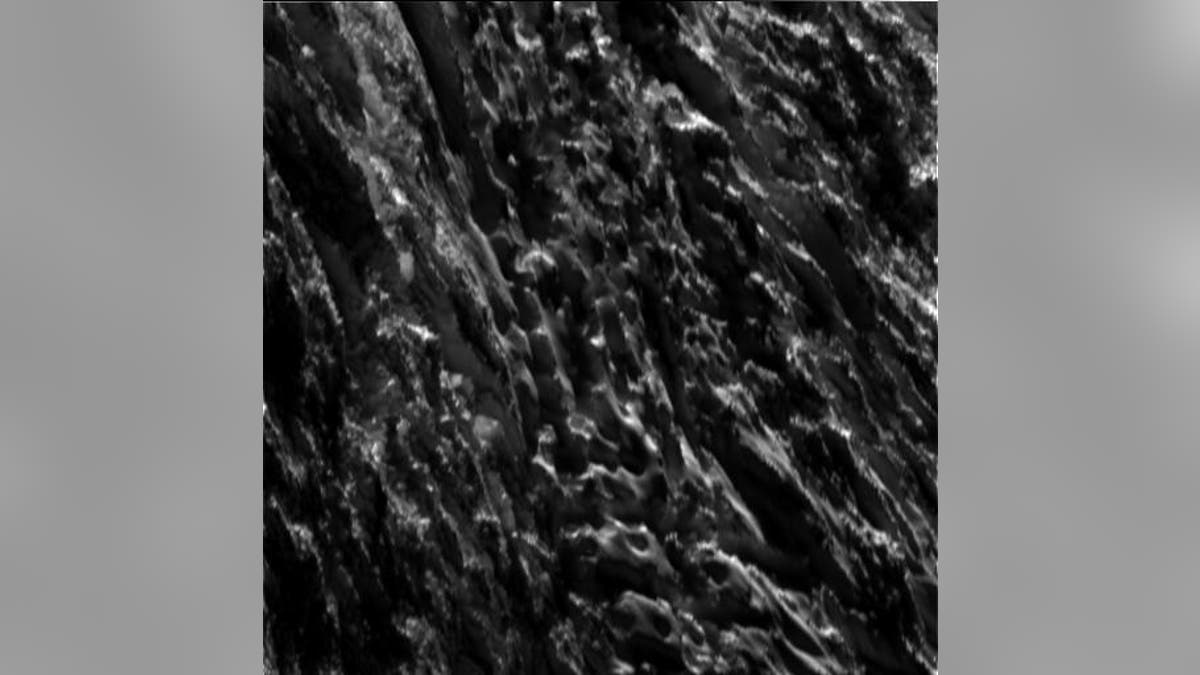

This unprocessed view of Saturn's moon Enceladus was acquired by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during a close flyby of the icy moon on Oct. 28, 2015. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

"Cassini's stunning images are providing us a quick look at Enceladus from this ultra-close flyby, but some of the most exciting science is yet to come," said Linda Spilker, the mission's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in a statement.

Enceladus boasts an icy, barren landscape riddled with deep canyons, dubbed “tiger stripes.” Beneath its icy exterior is an ocean, heated in part by tidal forces from Saturn and another moon, Dione.

This unprocessed view of Saturn's moon Enceladus was acquired by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during a close flyby of the icy moon on Oct. 28, 2015 (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

Related: Cassini gets close encounter with Saturn's moon Enceladus

Among the goals of the flyby is determining how habitable the ocean environment is within Enceladus. There is the possibility that microscopic organisms similar to those that thrive around Earth's deep sea volcanic vents might exist there. To help answer the habitability question, scientists will be trying to determine how much hydrothermal activity is occurring within Enceladus.

Related: NASA releases striking new images of Saturn's moon Enceladus

Scientists also expect to learn more about the chemistry of the plume on Enceladus. The low altitude of the encounter should offer Cassini greater sensitivity to heavier, more massive molecules, including organics, than the spacecraft has observed in previous efforts.

The flyby should also help settle a debate about what makes up the plume - column-like, individual jets, or sinuous, icy curtain eruptions -- or even a combination of both. The answer would make clearer how material is getting to the moon's surface from the ocean below.