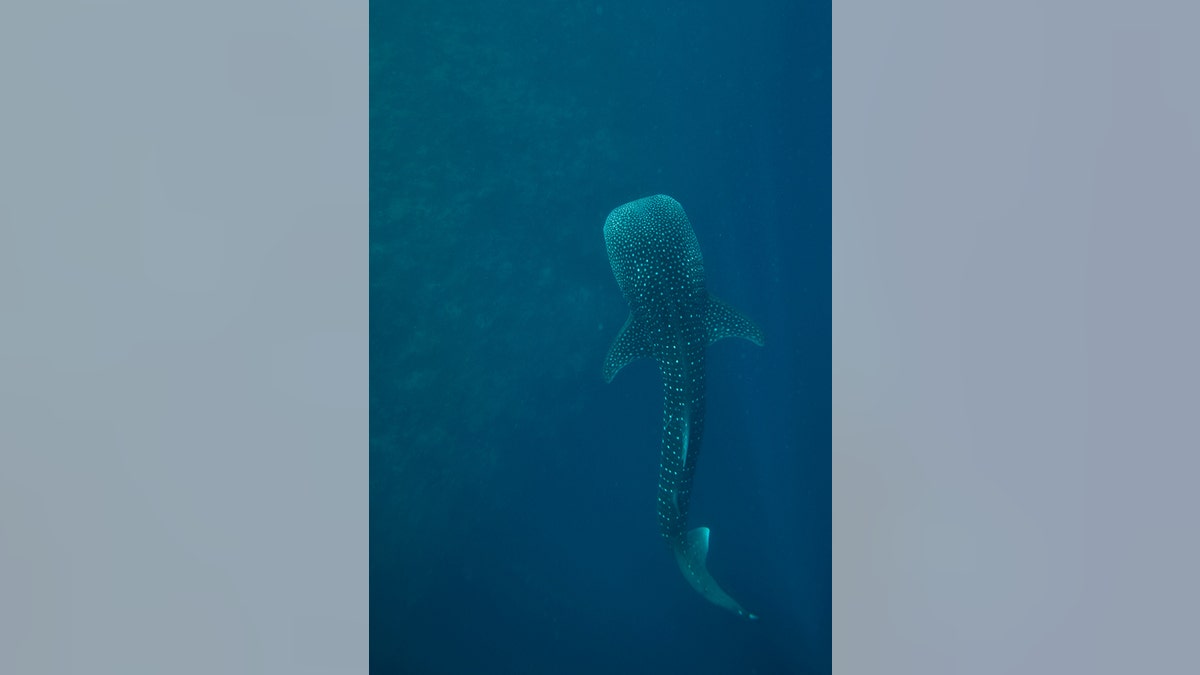

Whale sharks can grow to be over 30 feet (9 meters) long. (Simon Thorrold, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institutio)

Though whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the largest fish in the ocean, they have remained quite mysterious to scientists.

No one has seen these school-bus-size creatures mating or giving birth, little is known about their migration patterns and global population size, and scientists have found only a dozen sites on the planet where whale sharks congregate. But researchers recently found a new hotspot for the big fish that could offer clues about their life history.

In the Red Sea, hundreds of juvenile whale sharks gather around coral reefs near Al-Lith, a town on the central coast of Saudi Arabia, a group of scientists reported last week in the journal PLOS ONE. [Image Gallery: Mysterious Lives of Whale Sharks]

Researchers first learned about the possible aggregation site from local dive operators, who frequently saw the fish while navigating around the Shi'b Habil reef. Starting in 2009, the scientists put on snorkeling masks and jumped from a research boat to fix satellite-tracking tags on the dorsal fins of 57 whale sharks feeding in shallow water in the area. Over the next several years, the team tracked the movements of 47 of these creatures. (They didn't receive data from all the tagged sharks; in total, they tagged 21 female whale sharks, 18 males and 18 of undetermined sex.)

The data from the tags showed that whale sharks in this area often dove to at least 1,300 feet, though the deepest dive recorded was 4,462 feet. Only 10 percent of the sharks the scientists studied migrated to the Indian Ocean; most stayed in the southern Red Sea.

Among the known whale shark aggregation sites, the hotspot near Al-Lith is unique for the number of females present.

"While all other juvenile whale shark aggregations are dominated by males, we found a sex ratio of 1:1 at the site in the Red Sea," study co-author Simon Thorrold, a biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said in a statement.

Previous studies have found that females might live in different parts of the ocean than males, but it's not exactly known when this change in habitat use occurs. Thorrold and colleagues think the southern Red Sea hotspot and the previously studied juvenile aggregation site near Djibouti may be crucial juvenile habitats for adult populations in the Indian Ocean. The researchers say it is possible that other undocumented hotspots await discovery in the Red Sea.

"Eventually, this work will tell us about where whales sharks are spending their time throughout their lives where they're feeding, where they're breeding and where they're giving birth," Thorrold said in a statement. "Knowing where they go at different times of the year is critical to designing effective conservation strategies for the species."

Another new study of whale shark genetics, detailed in the journal Molecular Ecology, suggests there are two separate populations of whale sharks one in the Atlantic Ocean and one in the Indian and Pacific oceans that rarely mix.

Perhaps the biggest known whale shark aggregation site is off the Yucatan Peninsula, where the animals vacuum up fish eggs and plankton with their huge mouths each summer. By studying the annual feeding frenzy, scientists have answered some key questions about the elusive species' feeding habits, namely how and how much whale sharks eat. Scientists have discovered that special pads in the whale sharks' mouths help the animals filter plankton and that water passes through these pads at a special angle to prevent the floating snacks from getting clogged in the filters. And according to a 2010 study in the journal Zoology, these giant fish, which can grow more than 30 feet in length, don't consume as many calories as expected just 6,721 calories per day, which is low considering humans might take in 2,500 calories per day.

Whale sharks are sensitive to overfishing; like other shark species, they are slow to reach sexual maturity and have relatively small litters of pups, which means they cannot readily bounce back from big population losses. Thorrold and colleagues wrote that neither Saudi Arabia nor Djibouti harvest whale sharks, but the creatures may be threatened by ship strikes, as about 17,000 vessels pass through the Suez Canal each year.