War Games: 'Space nets' used to clean up dangerous debris

Allison Barrie on the technology being employed to capture 'space junk' before it causes problems

Technology thousands of years old has been overhauled to capture threats to space hardware.

Space junk poses a serious threat, particularly to humans in space whether in the International Space Station, space shuttles, or other spacecraft.

The debris also poses a threat to satellites, which fulfill a critical role for militaries, governments, and businesses. Satellites, for example, help provide television, weather data, phone services and GPS navigation to the public.

The only way to protect current and future missions, as well as the satellites essential to everyday life, is to remove threats lurking in space.

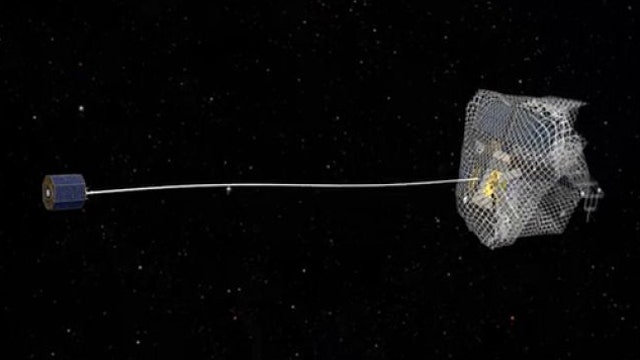

The solution? Fishing. Recent tests for space age ‘space nets’ by the European Space Agency have proved very successful.

While fishing nets have been in use for several thousand years, space nets take this this ancient piece of technology to a whole new level.

The hope is that nets could be deployed to capture and remove space threats.

The threat

Earth is entirely surrounded by a “halo” of junk in space. Space debris can be natural, like meteroids, or can be manmade.

There are more than half a million pieces of debris and, according to NASA calculations, at least 17, 000 trackable objects larger than a coffee cup.

A collision with any of these could be catastrophic to a mission.

Why does the size matter?

Just a single centimeter-sized screw could hit a spacecraft with the impact of a hand grenade.

Space junk travels at speeds up to 17,500 mph – this velocity means just a teeny tiny piece of junk, like a fleck of paint, could damage a spacecraft or satellite.

Abandoned spacecraft, launch vehicle stages, and mission debris are just a few of the sources of junk large and small.

Some of the stuff up there is several tons and, clearly, a collision would have serious results. Some debris, such as batteries and leftover fuel, could also be explosive as a result of solar heating.

One collision could even produce a chain reaction of further collisions.

For example, a defunct Russian satellite collided with and destroyed a U.S. Iridium commercial satellite in 2009. This collision added more than 2,000 pieces of trackable debris to the space junk problem.

In another example, when China deployed a missile to destroy a satellite in 2007, an additional 3,000 pieces of debris was added to space.

The tests

The ESA announced that its cutting-edge nets passed orbit testing with flying colors this week.

To test the nets in a space-like atmosphere, Canada’s Falcon 20 aircraft flew parabolic arcs. Each arc provided 20 seconds of weightless conditions as the plane fell through the sky and cancelled out gravity.

Over the course of 21 parabolas and two days, twenty net tests were conducted inside the aircraft.

The rainbow-colored nets were packed inside paper cartons. Each corner was weighted to help it entangle its target. A compressed air ejector shot the net at a satellite. The thinner version of the net proved more successful than the thicker one.

The ESA reported that the nets worked so well that they usually had to be cut away with a knife.

The National Research Council of Canada, Poland’s SKA Polska and OptiNav and Italy’s STAM were involved in the ESA project.

The challenges of capturing space junk

Capturing space junk is not easy. Standard space dockings are extremely difficult, but the ESA mission to capture derelict satellites adrift in the protected zone is even more challenging.

A satellite’s speed, size, and trajectory are just a few of the factors that make capturing space threats difficult.

One advantage of nets is they can be scaled to capture larger or smaller objects. Also, they can handle all sorts of target shapes, rotation rates, and speeds.

In addition to deploying nets, several other approaches have been considered like harpoon, tentacles and mechanical arms, and ion beams.

Mission 2021

ESA’s e.Deorbit mission aims to capture a large piece of space debris at least 4,000 kg – that’s nearly 9,000 pounds. After capture, the mission will remove it out of the Low Earth Orbit protected zone into the atmosphere or above the 1,243-mile LEO line.

Ballet dancer turned defense specialist Allison Barrie has traveled around the world covering the military, terrorism, weapons advancements and life on the front line. You can reach her at wargames@foxnews.com or follow her on Twitter @Allison_Barrie.