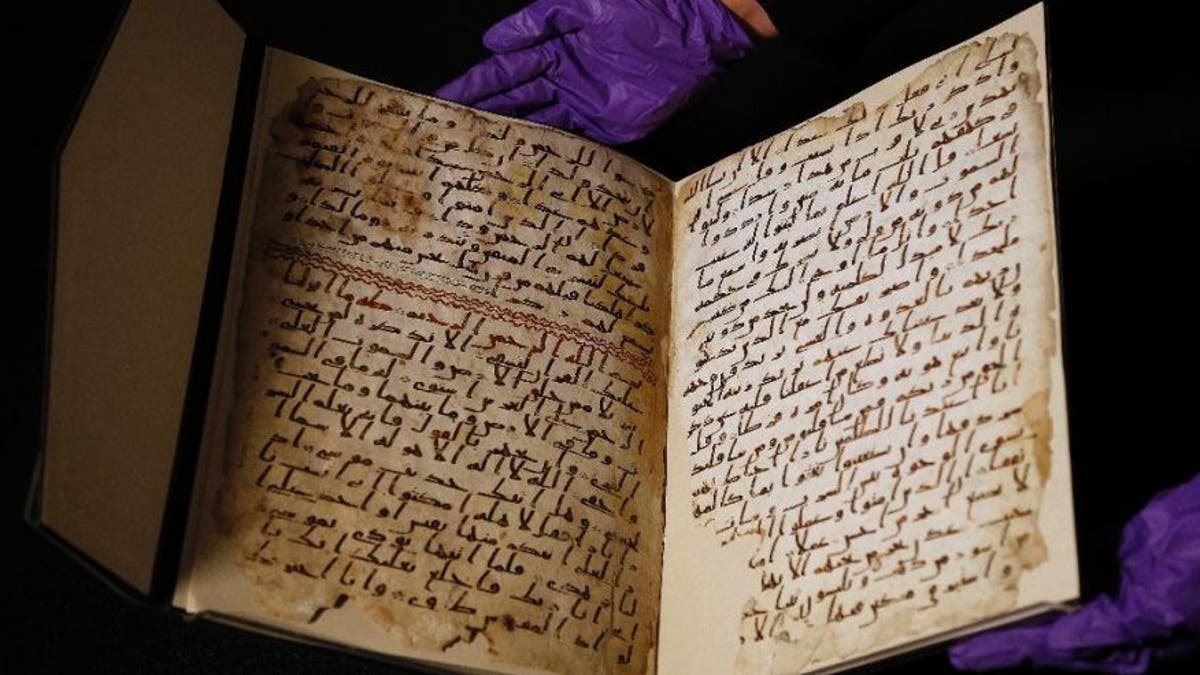

July 22, 2015: A university assistant shows fragments of an old Koran at the University in Birmingham, U.K. (AP Photo/Frank Augstein, The Associated Press)

Fragments of an ancient Koran, which scholars say may predate the accepted founding date of Islam by the Prophet Muhammad, are sparking intense debate with at least one expert saying that the manuscript’s writing belongs to a slightly later era.

The parchment leaves, which are held by the University of Birmingham in the U.K., underwent radiocarbon dating in a University of Oxford lab in late 2014. The research delivered a startling result when the leaves were dated to a period between 568 A.D. and 645 A.D.

Muhammad is generally believed to have lived between 570 A.D. and 632 A.D. The man known to Muslims as The Prophet is thought to have founded Islam sometime after 610 A.D., with the first Muslim community established at Medina, in present-day Saudi Arabia, in 622 A.D.

Radiocarbon dating works by measuring the ratio of two types of carbon atom in organic material.

However, Mustafa Shah, senior lecturer in Islamic Studies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), told FoxNews.com that the writing used in the ancient Koran is at odds with the radiocarbon dating. “[With] the style of the writing – it would be like saying you saw an iPhone in the 1990s,” he said.

Related: Fragments of world's oldest Koran may predate Muhammad, scholars say

Shah pointed to the distinctive style of the Koran’s script, with sporadic marks placed above letters, as well as the use of verse markers, as belonging to the Umayyad era, which began around 661 A.D. “Once the style and orthography of the script in these folios are taken into account, they bear all the hallmarks of a late 7th century codex,” he explained, in an email to FoxNews.com detailing the spelling. “Matching Qur’anic fragments from other collections have been placed within this sort of timeframe.”

David Thomas, professor of Christianity and Islam at the University of Birmingham, acknowledged the questions swirling around the Koran. “All we have got is a set of theoretical possibilities,” he told FoxNews.com. “It does bear features that are generally thought to have developed later in the history of Islamic calligraphy, but maybe what’s generally accepted about that history needs to be looked at with a fresh pair of eyes.”

Consisting of just two parchment leaves, the University of Birmingham’s manuscript contains parts of Suras (chapters) 18 to 20, written with ink in an early form of Arabic script known as Hijazi. For many years, the manuscript had been misbound with leaves of a similar Koran manuscript, which can be traced to the late 7th century, according to the university.

In a statement released in July, the university described the radiocarbon dating project as 94.5 percent accurate, placing the Koran among the oldest in the world.

However, the use of radiocarbon dating poses huge challenges for historians, according to Thomas. “Testing is destructive – whatever we send for testing doesn’t come back,” he explained. “We had the parchment dated because there was a small fragment hanging off one corner.”

Keith Small, Koranic manuscript consultant at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library agrees that, even with sound radiocarbon dating, there is still no definitive answer on the ancient Koran. “The early dating across its entire range [from 568 to 645] creates more questions for everyone than it answers,” he told FoxNews.com, in an email. “I think many of us are feeling we are having to adopt a position of suspending judgment until more information comes in,” he added.

Even radiocarbon dating the Koran’s ink may not provide the answers experts are looking for. “As far as I know, there is no satisfactory test available,” said Thomas. “Ink testing at the moment could only tell us the dates of the elements that make up the ink, not the ink itself.”

The professor also noted that ink testing could involve destroying part of the document, which raises ethical problems.

Nonetheless, the University of Birmingham is considering different strategies. “We’re looking at other ways to test the ink,” said Thomas. “It may be possible to dust over the surface and take off tiny [ink] particles.”

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers