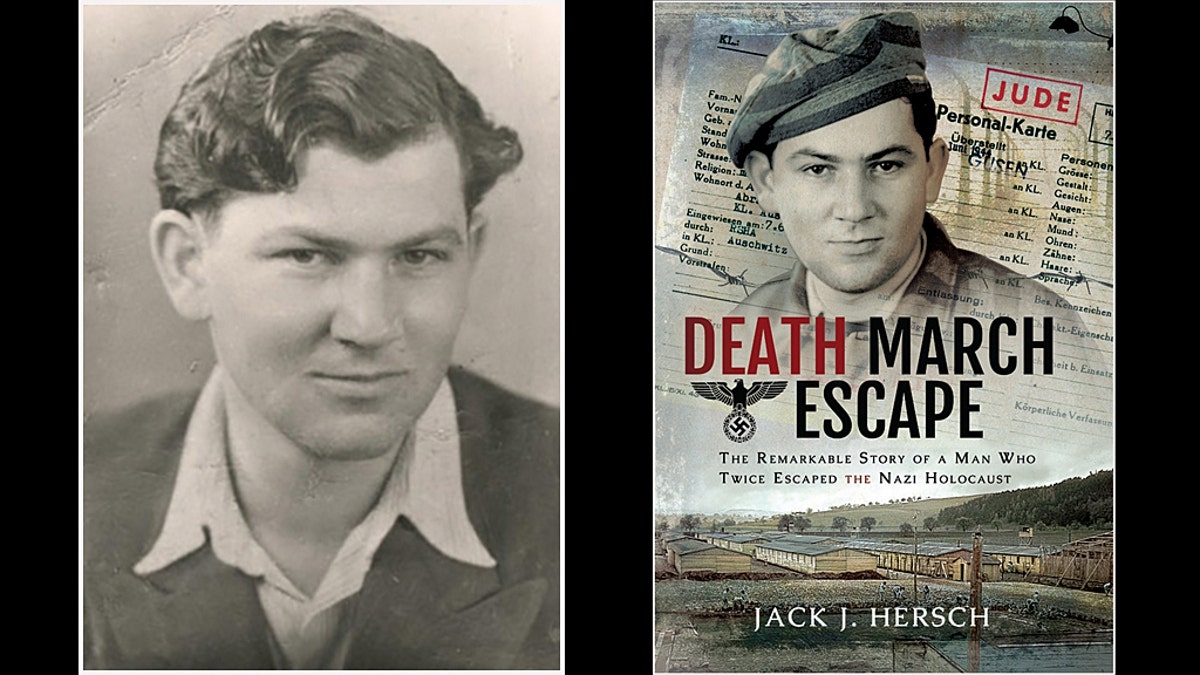

(Credit: Dave Hersch, Fox News)

At 5-foot-11, Dave Hersch weighed just 77 pounds. The 19-year-old from Dej, Hungary, had been whipped, starved and forced to move 50-pound rocks for a dozen hours per day, all at the hands of the Nazis.

“The concentration camp he was in, Mauthausen, was designed to work you to death,” said his son Jack J. Hersch, a 60-year-old businessman living on the Upper East Side. And yet, Dave still summoned the strength and willpower to escape the Holocaust — twice.

As chronicled in Jack’s book, “Death March Escape: The Remarkable Story of a Man Who Twice Escaped the Nazi Holocaust” (Frontline Books), out Saturday, it was April 1945 when Dave was sent on his first death march. It was a 34-mile trek from the Mauthausen camp in Austria to one called Gunskirchen. The hike was so strenuous that a good number of the 750 prisoners were expected to perish.

“Knowing the war was ending, Nazis wanted the Jews dead,” said Jack. “But killing 20,000 people in gas chambers is not trivial. It was easier to put them on the road and have them die while marching.”

At an intersection, the prisoners were pushed straight through. But Dave, who was lagging behind, turned right instead. He picked up a raincoat left on the ground and used it to blend in with the crowd.

“He must have done a calculus where there was a lower risk to go right than to go straight,” said Jack.

But freedom proved fleeting after the very woman who seemed poised to save Dave’s life — he knocked on her door and she fed him before letting him lie on the grass behind her home — turned him in to SS troops.

Dave was returned to Mauthausen, where he miraculously eluded punishment. Around 10 days later, he was sent on a second march to Gunskirchen. About a mile past the same intersection, he felt too weak to go farther. Dave ventured to the side of the road, all too aware that it could be the death of him. An SS trooper saw him and put a pistol to the back of his neck.

But the shock of cold, wet steel jolted him into standing. Perhaps impressed by this resilience, the trooper showed mercy and walked away. Dave then saw a small path that served as a shortcut to the town’s train station.

Reinvigorated by his near-death experience, “My father bolted down the path. Nobody saw him,” said Jack. “He spotted a dead man in civilian clothes and took his clothing. Then he slept under the cover of bushes.”

The next morning, Dave encountered an Austrian couple who hid him in their house. Three weeks later, “they told my father, ‘the war is over. You’re free to go,’ ” Jack said. Dave walked to town, where he found American medics.

He soon left Europe, making it to America in 1958 after a decade in Israel. Having lost his mother and four of his siblings in the Holocaust, he married wife Rachel in 1955 and they raised two sons on Long Island. Dave, who died in 2001 at age 76, owned assisted-living homes there.

In the course of researching his book, Jack visited what had once been the Mauthausen camp’s administrative office and is now, bizarrely, a family home. (“That people enjoy nice lives there made me angry,” Jack admitted.)

He also retraced his father’s marches and both escapes. “It’s one thing to hear the story. It’s another thing to walk it and to realize that if he had stopped five feet sooner, he would not have seen the path,” said Jack. “The degree of luck he needed . . . is mind-boggling.”

This story originally appeared in the New York Post.