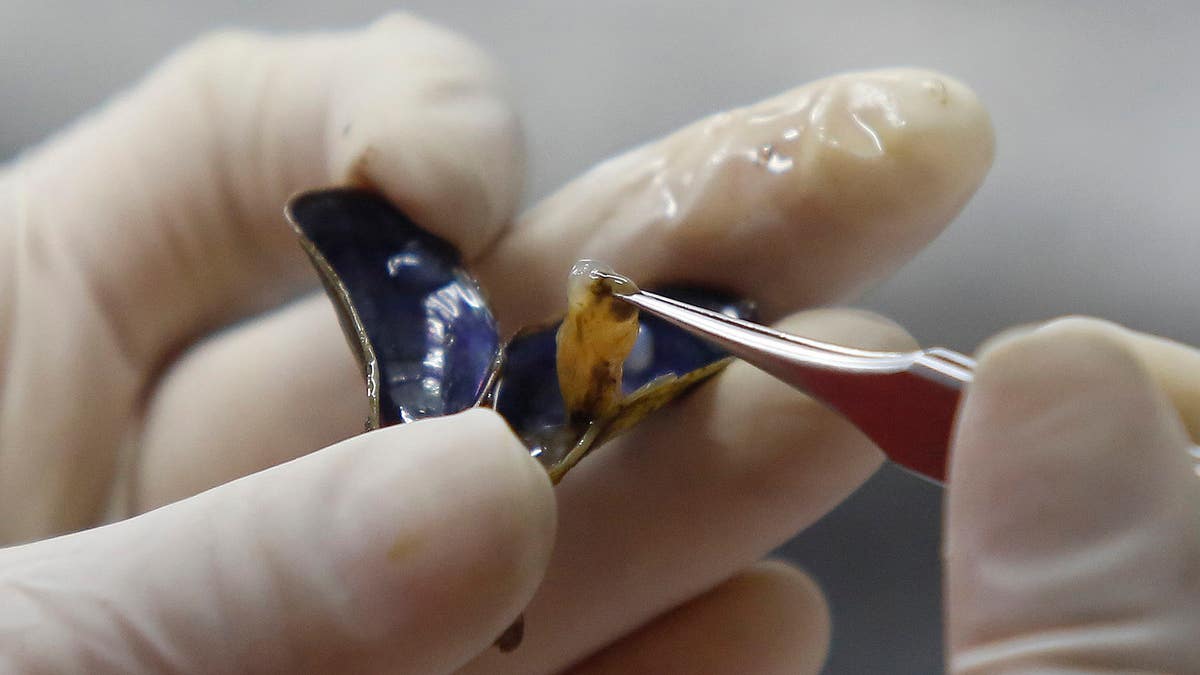

Jan. 29, 2015: Brazilian researcher Marcela Uliano da Silva tweezes a golden mussel out of its shell at the Carlos Chagas Filho Biophysics Institute, in Rio de Janeiro. (AP)

The world's mightiest waterway, the Amazon River, is threatened by the most diminutive of foes — a tiny mussel invading from China.

Since hitching its way to South America in the early 1990s, the golden mussel has claimed new territory at alarming speeds, plowing through indigenous flora and fauna as it has spread to waters in five countries. Now, scientists fear the invasive species could make a jump into the Amazon, threatening one of the world's unique ecological systems.

"There's no doubt the environmental effect would be dramatic," said Marcia Divina de Olivieira, a scientist with the Brazilian government's Embrapa research agency.

The golden mussel, which commonly grows to no more than an inch in length, is a hardy breeder, reproducing nine months a year by releasing clouds of microscopic larvae that float with the current to new territories. They attach to hard surfaces like river bedrock, stones, man-made structures and even each other, forming large reef-like structures.

They have devastated native clam species by attaching themselves onto the local mollusks, sealing them shut. Their ability to clog pipes has forced operators of hydroelectric and water treatment plants in Sao Paulo state, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and elsewhere to spend millions of dollars annually to clear them out with chemical drips or shut down turbines to scrape out giant mussel formations.

Golden mussels are filter-feeders, sucking in water and filtering out plankton and other microscopic bits of plant and animal life. Their proliferation can alter phosphorous and nitrogen levels in the water, producing blooms of toxic algae that can be deadly to aquatic creatures and humans.

While the thriving mussel colonies can mean more food for local fish and ducks, the disruption of the food chain can upset local systems, said Hugh MacIsaac, a professor at the University of Windsor, in Ontario, Canada, who studies invasive aquatic species.

"You clearly want to keep these out of the Amazon because if they were to get in, the potential consequences are very significant," said MacIsaac. "The key right now is you have to shut the door to make sure they can't spread further."

Researchers compare the golden mussel to the zebra mussel, a small bivalve originally from the Caucasus that colonized the Great Lakes in the United States in the late 1980s before spreading down the Mississippi River.

The advance of the golden mussels appears to have stalled at the sweeping Pantanal wetlands system in western Brazil, where natural cycles of rising and falling oxygen levels have kept the population in check so far.

But, the Pantanal is just 1,200 miles away from waters linked to the Amazon, and scientists fear that a boat towed overland could carry the invasive species clinging to a hull or that the ballast water used to stabilize a vessel could be contaminated by mussel larvae.

"If you just have a liter (of water) down in the bottom of a boat and put it on a trailer and travel over land to a new river system, you could be injecting potentially hundreds or even thousands of microscopic larvae into a new water body," said Steve Hamilton, an ecology professor at Michigan State University.

Brazil's government has been working to stop the golden mussel's progress for a decade, requiring ships headed to Brazilian ports to stop at least 200 miles off the coast and empty the ballast waters while far at sea. But experts complain the measure is spottily enforced.

One of Brazil's top experts on the mussel, a 27-year-old doctoral student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, believes she may have another solution: mapping the mussel's genome and engineering a virus or other "bio bullet" that could render the species infertile. The idea is similar to efforts to combat dengue-transmitting mosquitoes by making them sterile.

"If we manage it, it would be huge obviously from an economic point of view but also to protect biodiversity," said researcher Marcela Uliano da Silva. "The Amazon is under so many threats."

She's hopeful she'll succeed, but said it could take at least four years to carry out the plan.

Olivieira, the scientist with the Embrapa research agency, hailed Silva's work as a "perhaps one of the few paths that could actually help solve the problem."

"Even if it takes a long time, I believe it would be possible and it would be wonderful," said Olivieira, who said she's among just 50 researchers working on Brazil's golden mussel problem.

While the threat from the golden mussel might appear minor compared to hydroelectric dams, deforestation and sewage runoff from cities, Silva says that if the creature were to reach the Amazon, it could wreak havoc on one of the world's most biologically diverse regions. The Amazon has more freshwater fish species than any river in the world.

A study by Olivieira looked at which Brazilian waterways the golden mussel could colonize and found that the Amazon has the right temperature, calcium levels and acidity. That it hasn't arrived yet, she said, is "really a question of good luck more than anything else ... all it takes is just one introduction."

"Sometimes," she said, "we're really surprised that the animal hasn't gotten to the Amazon already."

Specialists like Demetrios Boltovsky, who studies the golden mussel at the University of Buenos Aires, believes the "extremely resourceful" mussel, with its knack for hitchhiking, eventually will enable it to reach the Amazon on a ship, either up one of the river's many tributaries or through the mouth of the main waterway.

"Certainly these animals will get there, if they aren't there already," he said.