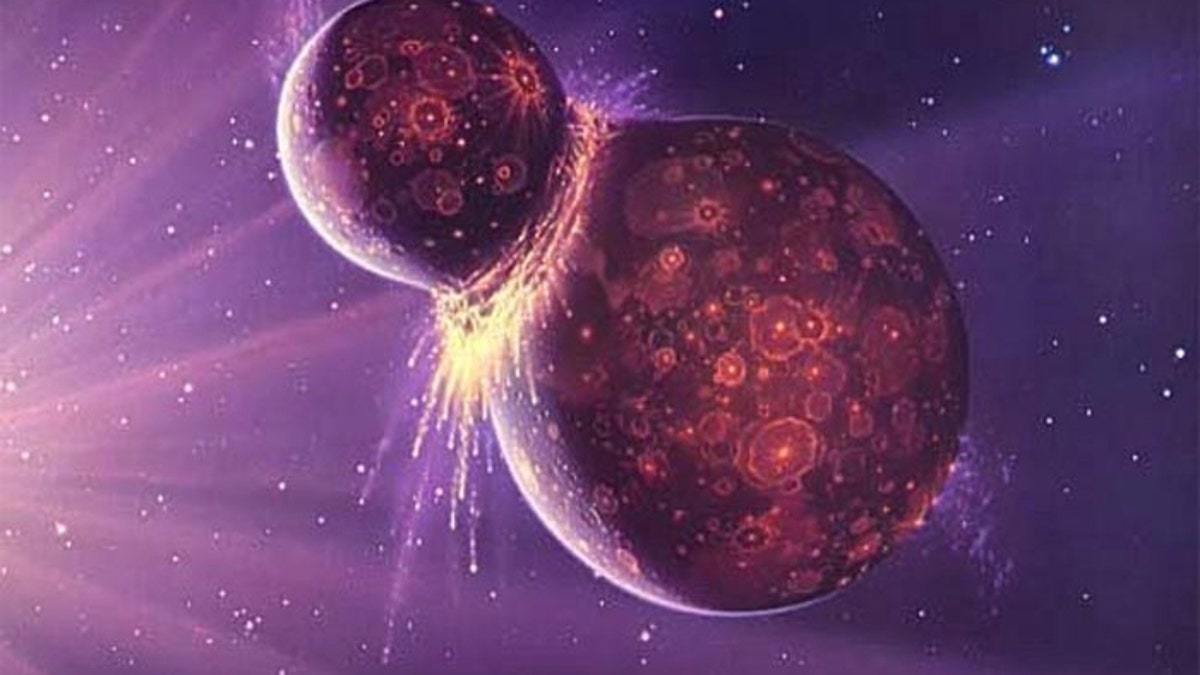

The moon may have formed when a large protoplanet slammed into the forming Earth. New research suggests that collision was energetic enough to fully scramble the worlds' materials. (NASA/GSFC)

The collision that created the moon must have been so powerful that it caused the material of the young Earth and the large body that hit it to completely blend, new research suggests — and water must have already been on the surface of Earth before the moon-forming crash.

The insight comes from the largest study to date comparing Earth and lunar rocks, finding that our planet and its natural satellite have a much more similar composition than is common between bodies in the solar system.

Richard C. Greenwood, a research fellow at the School of Physical Sciences at the Open University, in the U.K., and his colleagues analyzed rocks from every Apollo mission and compared them with a large collection of rocks taken from the deep ocean seabed. They focused on oxygen, which makes up to 50 percent of the analyzed rocks. [Should We Open Some Sealed Apollo Moon Samples?]

"Oxygen is the third most abundant element in the solar system after hydrogen and helium," Greenwood, the lead author on the new work, told Space.com. "In general, when a meteorite arrives on Earth, it has a very distinctive oxygen isotope composition compared to Earth.

More From Space.com

"For instance, we can identify rocks from Mars very easily by [their] isotope composition," he added.

When the researchers analyzed Earth and moon rocks, however, they found that oxygen isotope composition in the samples differed by only 4 parts per million (ppm).

"The fact that the Earth and the moon are so close is extraordinary," Greenwood said. "It really does show that the Earth and the moon really must have formed during some very, very high energy impact event that was really able to mix everything together and homogenize everything together."

Researchers first postulated in the 1970s that the moon and the Earth as we know them were created in a powerful collision between a proto-Earth and a body about the size of Mars some 4.5 billion years ago. Originally, researchers thought the moon formed predominately from material delivered by the impacting body and contained a much smaller component from the proto-Earth. But if that really was the case, Greenwood said, the oxygen isotope compositions of the Earth and moon should be distinctly different — whereas here they are more similar by an order of magnitude than anything else in the solar system.

"The original identity of this impactor got completely lost because it got completely mixed up with stuff from the Earth," Greenwood said.

The minuscule difference between the two bodies could be explained by asteroids and meteorites that have hit the Earth since the moon-forming collision.

Water survived

The fact that the two bodies are so similar also suggests that water must have been on Earth already before the collision — and more important, that it survived the apocalyptic smash. (Some previous work hypothesized that any water would have been lost, and therefore the current water on Earth came later.)

"The likely source of water on Earth are carbonaceous chondrites, a type of stony meteorites," Greenwood said. "But they have a very distinct oxygen isotope composition; if they had arrived after this event, we would see it, there would be a greater difference [in the oxygen isotope compositions of Earth and the moon] than there actually is."

The fact that water had survived on Earth despite the massive collision is good news, according to Greenwood. It suggests that the life-bearing substance can likely be found on suitable planets outside the solar system, despite the fiery process of planetary evolution.

"There are other exoplanets outside the solar system that have been shown to undergo at the end phase of their formation a very large impact," Greenwood said.

"But our paper shows that water is actually a very tenacious stuff. You can totally melt and vaporize your planet and the water still hangs around."

The new work was detailed today (March 28) in the journal Science Advances.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.