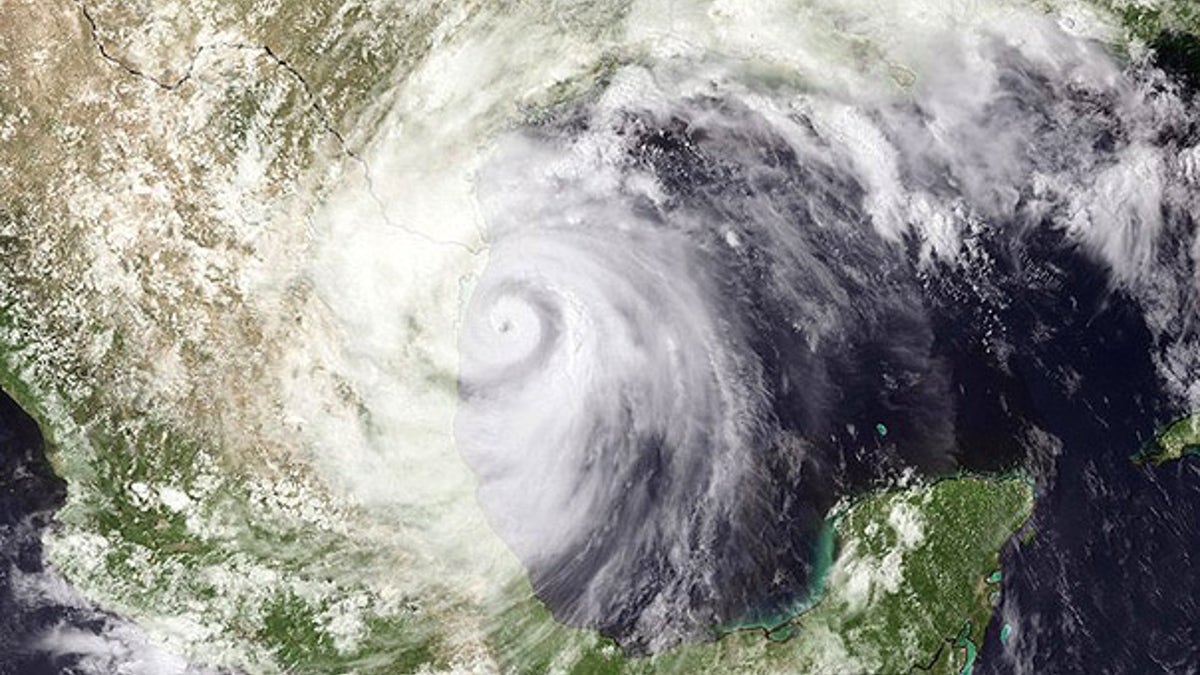

June 30: Hurricane Alex is seen lashing the Mexico coastline, south of Brownsville, Texas. (NOAA)

Alex may have cooled off, but hurricane season is just starting to heat up in the Gulf of Mexico. And absurdly warm oceans combined with still air mean storms will continue. Could Bonnie, Colin, Danielle and the rest of the forthcoming storms spell disaster for BP's oil spill?

Three major forecasts from the National Hurricane Center (NHC), Accuweather and Colorado State have all called for dramatic hurricane seasons this year. Those predictions aren't particularly meaningful, oddly enough -- and that comes straight from the forecasters themselves.

"The seasonal forecasts are of interest to a lot of people, but they're not terribly accurate," admitted James Franklin, branch chief of the NHC's Hurricane Specialists Unit. And not particularly meaningful, he says. "Even if we did do a real good job hitting it year after year, it doesn't give you a good indication of where storms are going to go."

Still, the guidance is useful. And if the first Atlantic hurricane of the season is just a taste of the season to come, we're in for a bumpy -- and lengthy -- season.

So what causes hurricanes, and why is this season so dangerous?

"The basic idea of a hurricane is one of a heat engine," Franklin told FoxNews.com. It converts the energy of the ocean into gale force winds. And this year, the ocean has far more energy than usual.

When waters are above about 80 degrees, conditions are ripe for hurricanes, and they can get much hotter in the tropics. "Waters in the tropical Atlantic between Africa and the Lesser Antilles are just about as warm as we've ever seen them," he said.

How much warmer? In a recent update to their annual forecast, Colorado State's Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray describe them as "running at near-record warm levels."

For a hurricane to be created, some pre-existing disturbance near Africa, a low-pressure system for example, forms the spark from which the hurricane will ignite. That tropical weakness moves out into the balmy waters of the Atlantic and gasses up.

The second big factor is wind. Strong winds in the upper air disperse tropical waves, disrupting hurricane formation and scattering pent-up heat. The NHC is predicting much more favorable wind patterns this year than last year -- La Nina or neutral conditions, as opposed to the El Nino conditions of strong winds from last year.

"In order to make a hurricane go, the heat coming from the ocean and released in a rising motion in the atmosphere has to be concentrated in one place. If winds in the atmosphere are blowing in different directions, that disperses heat." So having uniform winds is important -- and a rare event.

Dry air also means water vapor can't condense, clouds don't gather, rain doesn't fall and hurricanes don't form.

A third factor is the cyclical nature of the weather. Hurricane activity tends to run in long, 20- to 30-year cycles. Since 1995, we've been in a cycle of increased activity.

Alex didn’t move over the Gulf oil spill directly, so scientists and meteorologists were unable to directly observe the effects of the weather on the oil. But Franklin thinks we'll see winds dispersing the oil -- something BP has actively tried to do itself. In that sense, hurricane season may be a blessing for the oil crisis.

Klotzbach and Gray agree.

"If the storm tracks to the west of the oil, there is the potential that the counter-clockwise circulation of the hurricane could drive some of the oil further toward the U.S. Gulf Coast. Alternatively, a storm tracking to the east of the oil could push the oil further offshore. But, little is understood about the interaction of tropical cyclones and oil," the scientists write.

Fortunately, there's no evidence to suggest storms will suck the crude into the clouds, creating a foul rain of oil on coasts. But weather forecasters don't know enough at present to really predict what will happen. And Franklin is optimistic that BP technicians will cap the well and clean the oil before what-ifs turn into learning situations.

"Hopefully we won't learn anything about it."