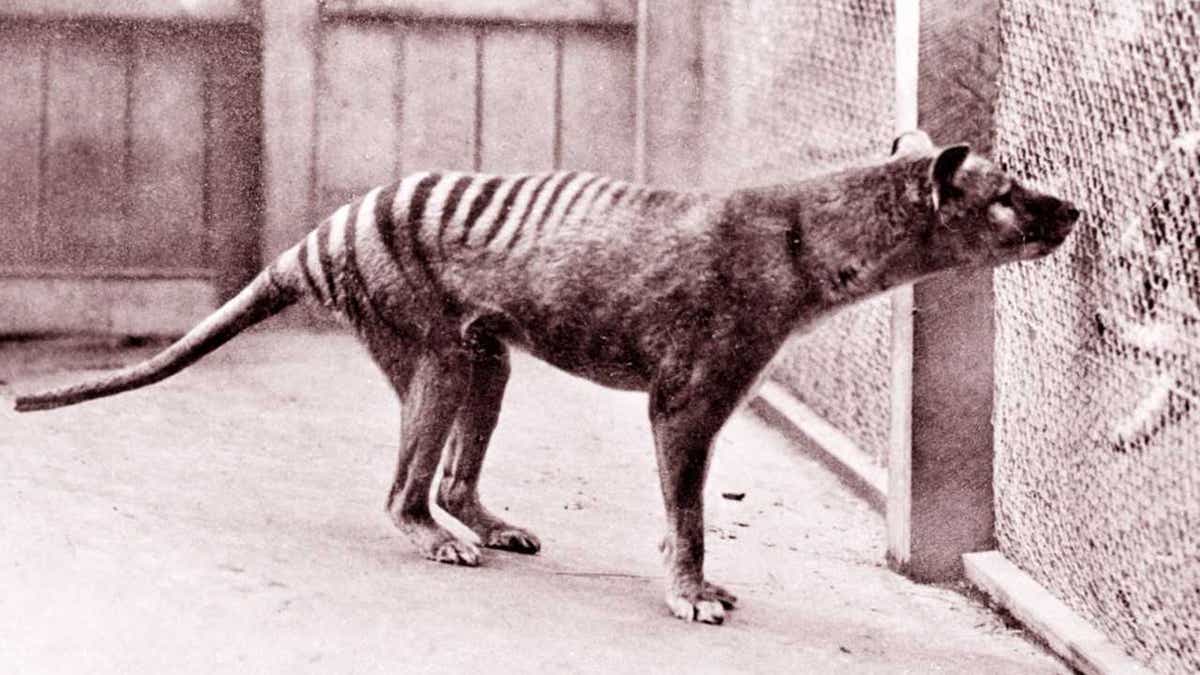

Benjamin, the last Tasmanian tiger in captivity, died in September 1936. (Credit: Getty Images)

The last thylacine, more commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, died in captivity in September 1936, more than 80 years ago.

A creature that first appeared 4 million years ago, the thylacine became extinct for a number of reasons, such as encroachment by humans on its territory, and disease.

But now, thanks to advancements in DNA research, some scientists believe it may be possible to bring it back from extinction.

According to a new study in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists have been able to find the complete nuclear genome of the thylacine. A team led by developmental geneticist Andrew Pask of the University of Melbourne sampled tissue from a one-month old thylacine found in 1909 in its mother's pouch. The sample had been preserved in alcohol.

245-MILLION-YEAR-OLD FOSSIL LOOKS LIKE DARTH VADER, SCIENTISTS SAY

Tasmanian tigers have long been a source of curiosity, nearly 80 years after their extinction, due to their odd appearance.

Don Colgan, Head of the Evolutionary Biology Unit at the Australian Museum, speaks under a model of a Tasmanian Tiger at a media conference in Sydney as seen in this May 4, 2000 file photo regarding the quality DNA extracted from the heart, liver, muscle and bone marrow tissue samples of a 134 year-old Tiger specimen (R) preserved in alcohol. The last known Tasmanian Tiger died in 1936 after it was hunted down and wiped out in only 100 years of human settlement. - PBEAHULIOCU (File photo: Don Colgan, Head of the Evolutionary Biology Unit at the Australian Museum, speaks under a model of a Tasmanian Tiger at a media conference in Sydney May 4, 2000 regarding the quality DNA extracted from the heart, liver, muscle and bone marrow tissue samples of a 134 year-old Tiger specimen (R) preserved in alcohol. Credit: Reuters)

“They were this bizarre and singular species. There was nothing else like them in the world at the time,” Charles Feigin of the University of Melbourne, Australia, said in comments obtained by Nature.com. “They look just like a dog or wolf, but they’re a marsupial.”

The oldest thylacine, known as Dickson's thylacine, first apepared 23 million years ago, according to Australia's Lost Kingdoms. The largest version, known as Thylacinus potens, grew to be the size of a wolf and survived until approximately 8 million years ago.

The nuclear genome holds significant amounts of information about the thylacine population, which the team suspects began to shrink between 70,000 and 120,000 years ago, before humans lived on what is now known as Australia. Feigin believes that a cooling climate led to the habitat of both the tylacine, as well as the Tasmanian devil, shrinking.

SCARY MARSUPIAL LION WITH INCREDIBLY POWERFUL BITE ONCE DOMINATED AUSTRALIA

Can it be done?

University of Melbourne associate professor Andrew Pask said that getting the genome is the first move towards bringing it back, but cautioned a return would not happen anytime soon.

“It is technically the first step to bringing the thylacine back, but we are still a long way off that possibility,” Pask said, according to Nature.com. “We would still need to develop a marsupial animal model to host the thylacine genome, like work conducted to include mammoth genes in the modern elephant.”

Gene sequencing is still a relatively new technology, having only been around since the early 1970s, but Pask believes it is our duty to try and bring it back if we can.

“Ethically, we actually owe it to species like that, the species we wiped off,” Pask added. “If we could bring it back, we should.”

Others, however, are more skeptical of whether science can actually bring back the Tasmanian tiger from extinction.

University of California, Santa Cruz evolutionary geneticist Beth Shapiro has worked before with genome sequencing of extinct animals and said they cannot be brought back.

“The thylacine is extinct, because we made it so. We cannot bring it back,” Shapiro said. “When I see the videos or images of the last thylacines, these are harsh reminders of the pressing need to develop technologies to stop other species from becoming extinct.”

Follow Chris Ciaccia on Twitter @Chris_Ciaccia