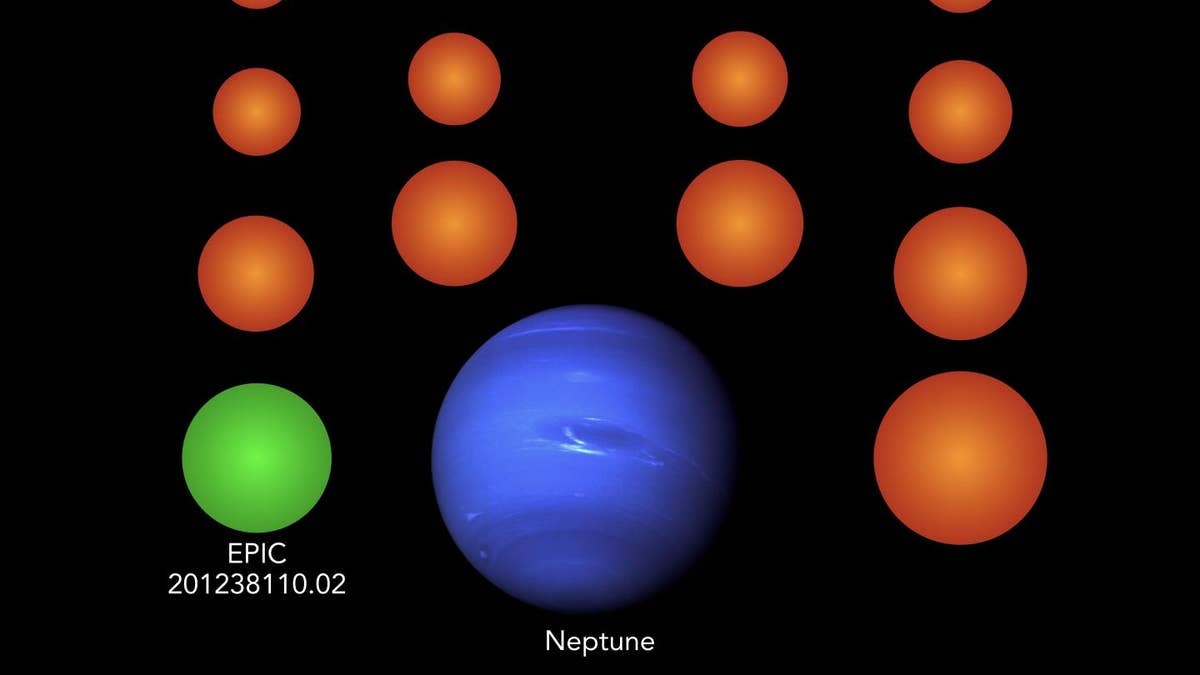

A diagram showing the sizes of the newly identified planets compared to Earth and Neptune. Only one of the 18 planets is at a distance from its star that could potentially allow liquid water to survive on its surface.

Scientists scouring old Kepler Space Telescope data have tracked down 18 more relatively small exoplanets imaged by the famed planet-hunting observatory.

While most of the planets orbit close to their parent stars and have scorching surface temperatures of up to about 1,830 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius), one world orbits a small red dwarf star in an area called the "habitable zone." That term is usually defined as the area around a star where a rocky planet could host liquid water on its surface. However, life is never a slam-dunk, and on this world, it would be particularly tricky because red dwarfs put out killer X-rays that could make living on nearby planets a challenge, even for microbes.

A new computer algorithm flushed out the hidden planets from data gathered by K2, Kepler's late-in-life observing program. K2 was developed after several of Kepler's gyroscopes (devices that allow a telescope to maintain a consistent orientation in space) had ceased working by 2013 after four years of operations in space, well exceeding their design lifetime.

Related: RIP, Kepler: Revolutionary Planet-Hunting Telescope Runs Out of Fuel

Scientists figured out how to stabilize the telescope's pointing using the constant pressure of particles streaming from the sun, hopping around from time to time to protect its sensors from solar light. Kepler found its planets using the "transit method," which notices when a planet passes in front of its parent star and produces a drop in brightness.

K2 allowed Kepler to observe 100,000 more stars before the telescope ran out of fuel in 2018, including 517 stars that scientists had already spotted planets orbiting. The researchers behind the new study decided to revisit those stars with a new data-processing algorithm.

"Standard search algorithms attempt to identify sudden drops in brightness," lead author René Heller, an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, said in a statement. "In reality, however, a stellar disk appears slightly darker at the edge than in the center. When a planet moves in front of a star, it therefore initially blocks less starlight than at the mid-time of the transit. The maximum dimming of the star occurs in the center of the transit just before the star becomes gradually brighter again."

The new algorithm attempted to plot a more realistic "light curve," or pattern of dimming as the planet moves across the face of a distant star. This made it easier to find small planets in the data: The new planets Heller and his colleagues found range from 70% the size of Earth to double our planet's size. The research team says their new algorithm also makes it somewhat easier to spot small planets amid natural brightness fluctuations of a star, such as those caused by sunspots, and other variables in observation.

More Earth-size exoplanets might be lurking in the data. Planets that orbit more frequently around a star have a greater chance of being spotted, because they pass in front of the star more often. But planets that are farther away might have gone undetected in the data, since their crossings are less frequent.

The researchers plan to apply their algorithm to the rest of the Kepler data, and say they may yield up to 100 new Earth-size worlds.

Two papers based on the research were published this month in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

- The 6 Most Earth-like Alien Planets

- The Most Fascinating Exoplanets of 2018

- Exoplanet Exploration: The Search Continues for New, Exciting Worlds

Original article on Space.com.