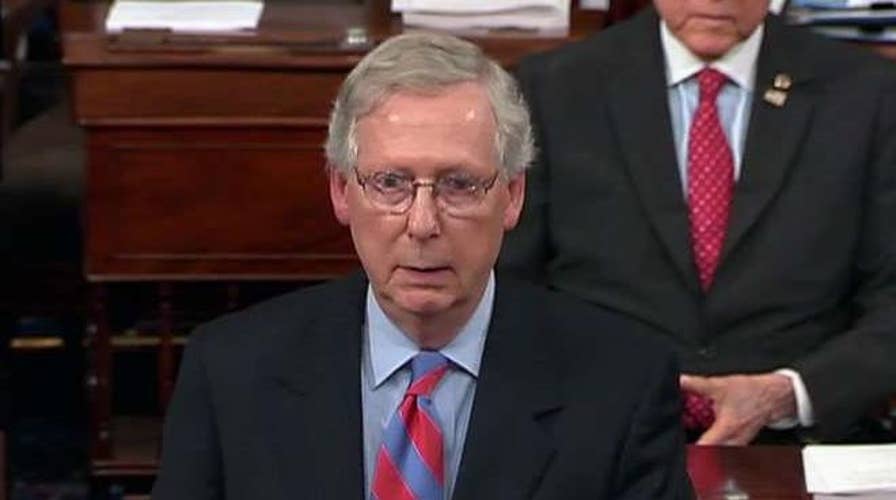

Sen. McConnell: Clearly a disappointing moment

Senate majority leader addresses Senate as 'skinny repeal' of ObamaCare fails after Republican Sens. McCain, Murkowski and Collins vote no

There’s a paradox on Capitol Hill right now and it requires some ‘splaining.

Congress isn’t in session. But it is. Yet nobody’s here. Lawmakers say they want to be in Washington. But they really don’t. So they aren’t. Yet they kind of are. And so even though the House and Senate aren’t in session, they’re meeting every three days for the next month.

Still, Congress is now taking its traditional August recess. But the chambers didn’t adjourn. So while lawmakers insist they’d rather stay in Washington and solve the nation’s problems, they insisted on going home. An “adjournment resolution” wouldn’t pass right now in either chamber. So Congress didn’t adjourn. But everyone left, even if lawmakers never voted to abandon Washington.

This is the parliamentary enigma that now envelopes Washington.

Is Congress really or really not on recess?

Yes and no.

The ambiguity is best summed up in the theoretical experiment posited by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Erwin Schrodinger. In the fictitious experiment, Schrodinger would place a cat in a steel box. Radioactive acid was then set up to potentially leak into the box. The cat can’t escape.

If the acid infiltrates the box, the cat dies. But no one can see into the box. So it’s impossible to know if the acid was released, killing the cat.

Therefore, Schrodinger argued, the cat may be both alive and dead. Nobody really knows until they see the cat and what happened to the acid. Schrodinger characterized this phenomenon as the “superposition of states.” The cat could be dead or alive. But nobody is certain until they observe the cat.

Schrodinger would have had a field day determining whether Congress was on recess or in session this August. Like Schrodinger’s cat, Congress appears to be in recess and in session.

However, unlike the theoretical experiment, it’s not clear whether simple observation could determine the precise parliamentary posture on Capitol Hill.

Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution states the following: “Neither House, during the Session of Congress, shall, without the Consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days.”

Both chambers frequently approve an “adjournment resolution” when Congress goes on hiatus for an extended period. That includes the summer break in August and often over Christmas and New Year’s.

The House and Senate often OK an adjournment resolution for lulls in the spring around the time of Easter and Passover, Memorial Day, Independence Day and Thanksgiving.

Otherwise, the House and Senate have to get together every three days unless there’s an agreement to skip town.

The House cut town in late July. The House Freedom Caucus, the chamber’s most conservative wing, pushed for lawmakers to stay in Washington.

A coalition of Republican senators lobbied Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., to keep the Senate in session for the first two weeks of August. The Senate deserted Capitol Hill on Thursday after only half a fortnight.

This leaves the House and Senate conducting brief “pro forma” sessions in which they simply gavel in and gavel out. The sessions run anywhere from a few seconds to at most, a few minutes.

The chambers usually don’t conduct legislative business. A skeleton staff is on hand. It’s rare to have more than one lawmaker in the House and Senate chamber. That person is simply there to preside over the abbreviated proceedings.

“Pro forma” is Latin for “the sake of form.” It’s a term used to describe a “formality,” satisfying only the minimum requirements.

The Constitution doesn’t state what the House and Senate must do when they meet or for how long. The Constitution only prescribes a huddle every three days. That’s why the pro formas consume so little time. Blink and you’ll miss one.

The House met for four minutes on Tuesday with Rep. Billy Long, R-Mo., presiding. On Friday, the House conducted what practically accounts for a marathon session. Rep. Andy Harris, R-Md., presided over the seven-minute conclave, elongated mainly because the House received a bunch of paperwork from the Senate.

The Senate set up nine pro forma sessions between early August and early September. The times vary widely -- 12:30 in the afternoon. 10 in the morning. 11:30 in the morning. Set your clock early for August 22. The Senate will meet at 7 a.m. that day.

But in reality, are the House and Senate really here?

No. A few members will drift in and out of Washington over the next month. Most are only here to preside over the House and Senate sessions. Many congressional aides are gone. The hearing rooms are dark.

Certainly work continues behind the scenes. But Congress truly isn’t “here” --- even though both bodies are technically meeting every three days to match the constitutional requirement.

Naturally, it looks bad for lawmakers not to “be” in Washington, toiling on legislation. That’s why someone long ago cancelled the term “recess.” The quasi-euphemistic term today is “district work period.”

Keep in mind, lawmakers often maintain hectic schedules when in their districts and states. Just because members aren’t in Washington doesn’t mean they aren’t busy. And if lawmakers weren’t back home regularly, constituents might excoriate them for spending “too much time in Washington.”

It’s a double-edged sword.

The House and Senate must each vote to approve an adjournment resolution if members intend to be away for more than three days. That means a simple majority must vote to leave town. But in this political environment, few would have voted to adjourn.

Imagine if House and Senate Republicans coughed up the votes to adjourn after the health care debacle? That’s to say nothing of the tranche of business that awaits the chambers in September: keeping the government open, a debt crisis, reauthorizing the Federal Aviation Administration and tax reform.

Congressional Republicans control both the House and Senate. They’ve achieved none of their major legislative promises. A vote to adjourn would be toxic.

A few years ago, the House defeated the adjournment resolution. Still, everyone headed for the airport. With only a few people around, the House quietly OK’d the adjournment resolution the next day.

So what if lawmakers did stay in Washington. Here’s something important: You cannot force political compromise and “deals.” If Republican leaders were “close” on health care, they’d be in session.

But they’re nowhere. Compelling lawmakers to linger in Washington with nothing that can pass is a bleaker proposition than sending everyone home.

There’s another reason Congress likely would have lacked the votes for an adjournment resolution this August: recess appointments.

President Trump tore into Attorney General Jeff Sessions a few weeks ago. Sessions told Fox News that the lashings were “hurtful.” But Sessions remains on the job. Loyalists on Capitol Hill rushed to Sessions’ defense, erecting a rearguard around the attorney general.

A theory drifted through Washington that the president would sack the attorney general and then make a “recess appointment” for the post. The Constitution provides an option for presidents to make “recess appointments” and bypass the traditional confirmation process should vacancies occur during a recess.

McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., made sure former President Barack Obama didn’t have the chance to make a recess appointment to the Supreme Court after Justice Antonin Scalia died.

That’s why the GOP-controlled House and Senate never adjourned all of last year following Scalia’s death. The House and Senate simply met every three days.

Obama tried to make recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau during the interstitial between the three-day sessions.

But the Supreme Court ruled that Congress determined it wasn’t on recess. After all, the Constitution grants both chambers the right to set its own rules. In other words, if the House and Senate say they are meeting, then they’re meeting.

Therefore, recess appointments aren’t available to Trump should he decide to fire anyone.

That’s because Congress is here. Even if it isn’t. The Constitution and the Supreme Court both say lawmakers have the right to say they’re here, even if they’re not.

Kind of like Schrodinger’s cat. Both dead and alive. Congress is both in session … and on recess.