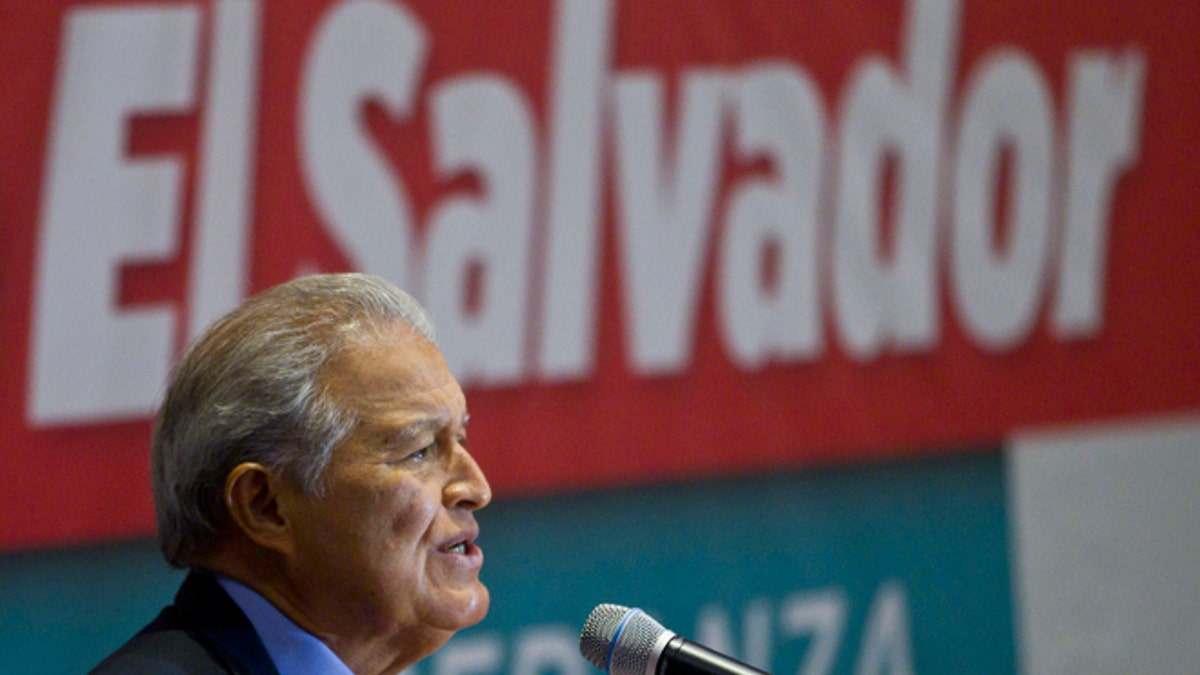

President-elect Salvador Sánchez Céren, of the ruling Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), speaks during a press conference one day after a presidential runoff election in San Salvador, El Salvador, Monday, March 10, 2014. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

When a guerilla leader was elected president of El Salvador this week – though opposition leaders have called for a recount – some started to wonder whether the country's close alliance with the U.S. would start to erode.

But experts say very little is likely change in regards to relations between the Central American nation and the United States after Salvador Sánchez Céren was chosen as its president.

Sánchez Céren, a former Marxist guerrilla during the country’s decades-long civil war and member of the leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) party, won by less than 6,400 votes over Norman Quijano of the right-wing Arena party. ARENA informed its members it had filed a complaint with El Salvador's attorney general, where it is presenting evidence of fraud, but so far it has not made any such evidence public.

Analysts looking at the elections say that the U.S. – home to an estimated 2 million Salvadoran immigrants - should make it known that the international community is watching, but should keep away from any direct interference.

“The U.S. should not overtly interfere in the election process, but can send a message to both campaigns to tell them that the situation is being watched and any unrest could be harmful for El Salvador both at home and abroad,” Jason Marczak, the deputy director of the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council told Fox News Latino.

- Presidential Election Returns In El Salvador And Costa Rica Indicate Runoffs

- El Salvador’s Too-Close-To-Call Election Has Both Sides Claiming Victory

- El Salvador Begins Evacuations As Chaparrastique Volcano Spews Ashes

- El Salvador, Costa Rica Vote For New Leaders, Political Stagnation On The Line

- El Salvador Presidential Elections: Former Guerrilla Leader Sánchez Cerén Declared Winner

- Best Pix From Latin America

The U.S. has so far remained quiet about El Salvador, with the exception of urging patience during the tense period following the election.

“We, of course, applaud the Salvadoran people for exercising their democratic right in peaceful elections that international observers called free and fair,” State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki said during a daily press briefing. “We look forward to working in close partnership with the candidate chosen by the people of El Salvador to be their next president.”

In terms of relations with the United States, El Salvador has a lot riding on a peaceful transition of power from current leader Mauricio Funes to Sánchez Céren – who is currently the country’s vice president.

There have been accusations from the far right members of ARENA that Sánchez Céren will lead the country down a path to become the next Venezuela or that more hardline members of the FMLN will try to distance El Salvador from U.S. influence because of its well-known involvement in El Salvador’s civil war.

These accusations, however, arose when Funes – a former journalist and the first president from the FMLN – was elected and relations under his administration have remained solid. Sánchez Céren has said he plans to model his presidency after Uruguay’s center-left President José Mujica and has promised to maintain good relations with the United States.

"Mujica is the example to follow, because he works on two main fronts: development and social investment," Sánchez Céren said, according to the Associated Press.

Both development and foreign direct investment are the two big gets for El Salvador in trying to maintain a solid friendship with Washington.

There is interest from U.S. businesses in creating textile production centers, advancing the shipping industry and possibly opening call centers similar to those in place in Costa Rica.

Along with business interest, there is the U.S. foreign aid agency the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) dangling $270 million in funds to El Salvador. The allocation of that sum has already been approved, but still needs to be signed and any fluctuations in U.S.-Salvadoran relations could throw that aid in jeopardy.

The real question is whether there are some elements of the FMLN who want to take a symbolic jab at the U.S.,” said Cynthia Arnson, the director of the Latin American program at Washington D.C.’s Woodrow Wilson Center. “It would be an incredibly foolish move that would be the death knell to the aid package.”

While the Salvadoran government’s official stance looks favorably on foreign direct investment in the country, some of the country’s small landowners and farmers worry that with the expansion of businesses they could be driven off their land. In a country comparable in size to Massachusetts and with over 6 million people, space is at a premium and some analysts say there is concern that small scale farmers will be the first victims of business development.

“What is worrisome is that El Salvador could become a prime victim of free trade,” said Larry Birns, the director of the Washington D.C.-based think tank the Council of Hemispheric Affairs. “What is at stake is the ability for the average campesino to gain land.”

From Washington’s perspective, besides trade and the large Salvadoran population residing in places like California and Maryland, El Salvador is a strategic ally in the U.S.’s battle against transnational organized crime in the region.

As part of the so-called northern triangle, El Salvador has not suffered the degree of narco trafficking violence and cartel incursion that has plagued neighboring Guatemala and Honduras.

Sánchez Céren will have to deal with one of the highest murder rates in the world. A 2012 gang truce seemed to cut the country's daily average of 14 dead by half, but the drop appears to have been short-lived as police statistics show 501 murders the first two months of this year, an increase of more than 25 percent over the same period of 2013.

Experts say, however, that gang violence is more of a domestic issue and so far Mexican and other trafficking organizations have not made inroads in El Salvador like in other countries in Central America.

“El Salvador has done relatively better,” Arnson said, “than other countries when it comes to organized crime.”