Daniel M. Cohen on a Singular Holocaust Survivor

Fox News' James Rosen speaks to author Daniel Cohen about his book 'Single-Handed' and the extraordinary life of Tibor 'Teddy' Rubin

Earlier this month, in a state court in Lueneburg, Germany, a former Nazi SS soldier was convicted of complicity in the murder of 300,000 Hungarian Jews who were deported to the Auschwitz death camp in the summer of 1944.

As the so-called "accountant of Auschwitz," 94-year-old Oskar Groening was not alleged to have taken part in the beatings or killings of Jews. But the court found that Groening's service at the camp gave him enough information about the horrors occurring there for him to know that continuing to support the enterprise, even in an administrative capacity, made him an accessory to murder. In sentencing Groening to four years in prison – a longer sentence than state prosecutors sought – Judge Franz Kompisch told the defendant: "You had freedom to think."

During the trial, Groening told the court he admitted to "moral guilt." But the white-haired former bank teller maintained that the enormity of the crimes of the Holocaust made it inappropriate for him to beg forgiveness from any of the Auschwitz survivors or their family members who testified at the trial – only God himself could grant that.

The verdict is widely regarded as perhaps the last opportunity the authorities in Germany, or anywhere else, may have to bring some measure of justice to Nazis involved in the Final Solution. The passage of 70 years since the end of World War II means that fewer and fewer firsthand accounts of the Holocaust are surfacing – and those that do come to light tend not to come from the ranks of the perpetrators, like the SS, but rather from the survivors of the concentration and extermination camps: a number that could have been as high as 100,000.

In those stories, some common themes became discernible over time. In "The Survivor: An Anatomy of Life in the Death Camps" (1980), author Terrence Des Pres wrote that uncontrollable factors, such as luck and randomness, often determined life and death for the inmates. But of those who did survive, Des Pres found two things invariably to be true: They were joiners and they were rules-breakers. This is to say: Lone wolves assuredly could not survive in places like Auschwitz, but those who belonged to an illicit support network of some kind conceivably could; and since the rules of the camp were not designed for the well-being of the inmates, but rather as yet another instrument of their torment and death, attempting scrupulously to follow the rules would surely lead an inmate to those grim outcomes.

Now, with so few veterans of the World War II era still with us, we are fortunate to receive a firsthand account of the Holocaust from a survivor whose story is – in the literal sense of the word – unique. Tibor "Teddy" Rubin, a Hungarian boy, was thirteen when his family was rounded up by the Nazis and shipped off to the Mauthausen concentration camp, in upper Austria, in the spring of 1944.

Upon its liberation by the U.S. Army in May 1945, Mauthausen was discovered to have been the scene of at least 95,000 murders, more than 14,000 of those victims being Jews. Rubin endured slave labor and other horrors there for more than a year. "When they freed me," Teddy later recalled, "I promised that I would join the U.S. Army and try to give back, because they saved my life."

And he did. Arriving in the United States nearly penniless and unable to speak English, Rubin in 1950 volunteered for service in the Korean War. His acts of heroism included singlehandedly defending a hill against an onslaught of enemy soldiers, braving sniper fire to rescue a wounded comrade, and commandeering a machine gun after its crew was killed. Then he was captured and spent two and half years as a prisoner of war. Drawing on his experiences at Mauthausen, Rubin managed to steal food for his comrades, saving the lives of up to 40 men. He returned to America in 1953, but it wasn't until 2005, at the age of 75, that Rubin was admitted to the White House and there presented, by President George W. Bush, with the Medal of Honor, America's highest military distinction.

"Tibor was captured trying to cross the border in Switzerland, and when he was entered into the camp, he was one of very few children," explained Rubin’s biographer, Daniel M. Cohen, in a recent visit to "The Foxhole." "Basically, he was considered a nothing [by the SS guards at Mauthausen]. They didn't bother with him, and that's to some extend why he survived. And then for a large period of time, maybe four or five months, he was taken out of the camp to a work camp in a forest – where he learned how to steal food from Nazis."

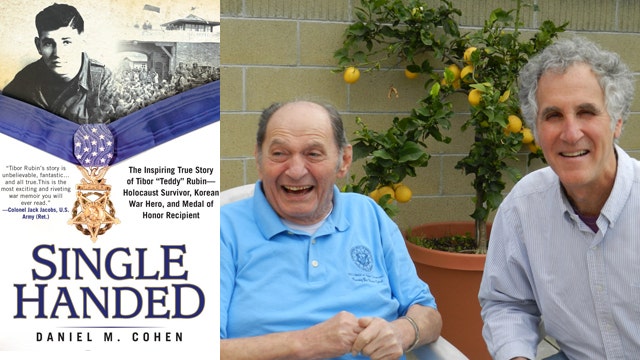

To research and write "Single-Handed: The Inspiring True Story of Tibor 'Teddy' Rubin – Holocaust Survivor, Korean War Hero, and Medal of Honor Recipient" (Berkley, May 2015), Cohen, a veteran filmmaker, drew on some 40 hours of conversations he recorded with Rubin, now 86, at the latter’s home in Garden Grove, California. "We laughed a lot," Cohen recalled. "Tibor's got a tremendous sense of humor, which I think comes across in the book, and it was like guys talking after the first few times."

Cohen recounted the time when Rubin, having successfully defended a critical stretch of hilly terrain in Korea, descended from his vantage point to see the corpses of lifeless North Korean soldiers he had just killed strewn pell-mell before him – and began to sob uncontrollably.

COHEN: [T]his was sort of death on a mass scale that he really caused, and he couldn't see it when he was defending the hill. It was dark, it was hazy, there was a lot of smoke, there was a lot of sand, and dust, and they were firing mortar shells at him, so he never really saw any of the actual guys that he killed, and had not been in that much combat. Some, but at distances.

ROSEN: Even though this was combat, and even though he was a motivated joiner of the United States Army, he still regarded killing the enemy as a kind of transgression upon the laws of God, as you say?

COHEN: Well you know, in the Jewish religion ... during the high holidays they remind you that the worst thing you could do – and there are a lot of bad things you could do – but the worst is to behave like your worst enemy. And that's essentially what happened here. Tibor found himself in the untenable position of having acted as badly as his enemy and maybe worse...

Asked how he had managed to survive the depraved cruelties of the Nazi camp system, Rubin would invariably say: "I was lucky." But his interviews with Cohen also make clear that Rubin met the two criteria for survivors: He broke camp rules and benefited from an illicit support network. "He would call himself 'the little rat,' because he would take anything he could," Cohen told me. "Did he do anything bad? He stole food whenever he could. At some point, he said, he would take it out of someone else's hand if he absolutely had to, but the seven Poles [he was captured with] looked after him for a while – as long as they could. They all perished."

Click here to watch the full episode of "The Foxhole" with guest Daniel M. Cohen.