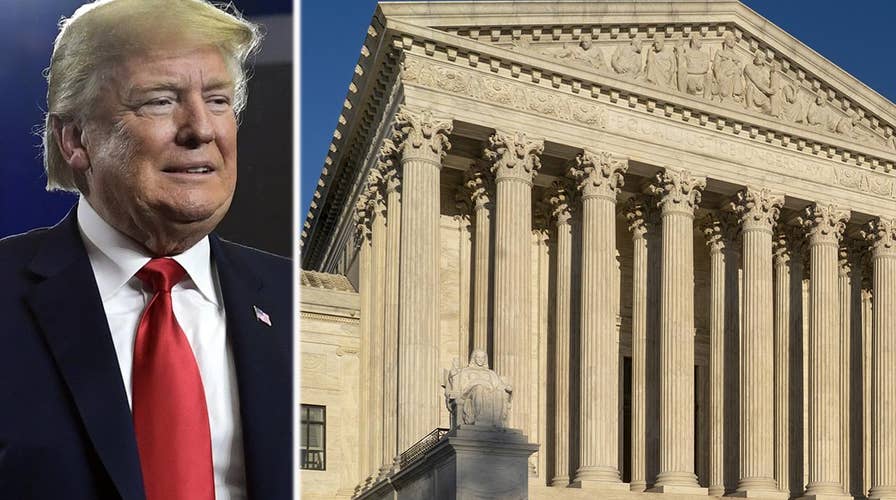

Trump calls Supreme Court decision 'a tremendous victory'

President Trump praises the Supreme Court's decision on his travel ban; chief White House correspondent John Roberts reports from Washington.

The Supreme Court’s decision Tuesday in Trump v. Hawaii – commonly referred to as the travel ban case – unmistakably reached the right result.

The court rejected some of the more outlandish attacks on the Trump administration’s immigration policies and also made clear that the left’s resistance will have to fight the president in the arena of the ballot box, rather than the courtroom – as the Constitution fundamentally requires.

In an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, a 5-4 majority upheld the Trump administration’s use of the power delegated to the president by an act of Congress to ban the entry of foreigners from countries deemed threats to national security.

The high court’s opinion reflected views of presidential authority, national security and congressional control over immigration that the court has repeatedly endorsed.

The decision was not a broad expansion of executive power, as critics allege. Rather, it fell squarely in line with the Supreme Court’s leading precedents. The court soundly rejected novel and implausible arguments that would have wrenched the constitutional allocation of powers loose from its long-fixed moorings.

Critics of the travel ban made two main arguments. The first was statutory, based on a reading of the immigration laws. The second was constitutional, and relied on the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The court’s rejection of the statutory argument was almost a no-brainer. Congress had by law delegated the president sweeping power over the entry over foreigners into the United States. In doing that, it had confirmed and reinforced the president’s inherent power as chief executive.

Going back at least to the Supreme Court’s 1936 decision in the case of Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., the court has consistently upheld such broad delegations of Congress’ power, especially in the sensitive areas of national security and foreign policy, with which immigration obviously intersects.

Such statutory delegations dovetail neatly with the president’s purely constitutional authorities. Liberals have usually applauded such broad transfers of congressional power to the administrative state when the subject is environmental protection or market regulation. With the boot on the other foot here, the lockstep-liberal bloc of four on the Supreme Court dissented.

Trump v. Hawaii aligns closely with another major Supreme Court precedent – the opinion of the New Deal Justice Robert Jackson in the Steel Seizure case, which arose out of President Truman’s seizure of privately owned steel mills during the Korean War.

Jackson’s view that the power of the president is at its highest point when pooled with the power of Congress fits the travel ban case perfectly. And Jackson’s opinion is also iconic for liberals. Yet it had no force for them here.

The majority opinion in the travel ban case relied heavily on a third major precedent – the Court’s 1993 decision in Sale v. Haitian Centers Council. That opinion, which commanded an 8-1 majority, was written by Justice John Paul Stevens, one of the court’s most committed liberals.

In the Sale case, the high court upheld the Clinton administration’s policy of ordering the Coast Guard to interdict thousands of Haitians fleeing a dictatorship in their home country and desperately attempting to find safety in the United States by risking their lives on the high seas.

Judged by the standards of common decency, the Clinton policy was far more reprehensible than anything the Trump administration has done regarding immigration. Moreover, Clinton administration actions against the Haitian boat people was condemned as a human rights violation when reviewed in 1997 by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. However, so long as the Sale precedent stands, it supports the legality of Trump’s travel ban.

We turn now to the more important part of the travel ban opinion – its constitutional side.

The implications of the Supreme Court’s ruling here are critical for the future of the Trump administration (and indeed, all future administrations). The court rejected the claim that President Trump had violated the Constitution because of his personal bias against Muslims.

Although earlier versions of the travel ban had applied only to Muslim countries and had granted an exception for Christians, the Trump administration revised the ban. It in the form in which the ban came before the Supreme Court, it reflected no religious or ethnic bias on its face.

Nevertheless, President Trump’s political opponents (who included the lower federal court judges in Hawaii and California) claimed that the president’s personal state of mind was subject to judicial review and could be deduced from his statements, tweets, and the like both before and after the 2016 election.

Rejecting this argument, the Supreme Court stated that if President Trump’s executive order is facially legal and can be justified on a legitimate national security basis (as the president’s order was), the federal judiciary should not block it.

“Under these circumstances, the Government has set forth a sufficient national security justification to survive rational basis review,” the court’s majority decision said. “We express no view on the soundness of the policy.”

To have allowed such an aggressive form of judicial review would have paralyzed the Trump administration and future presidents by subjecting to challenge virtually any presidential decision, even if facially legal, based on their hidden state of mind.

While Trump critics may oppose his immigration policies, the Supreme Court reminds us all that the proper forum to fight it remains the political process – by electing members of Congress, who can always retract the delegation of authority to the president, or by electing a new president, who can issue new orders.

Robert J. Delahunty is a law professor at St. Thomas University.