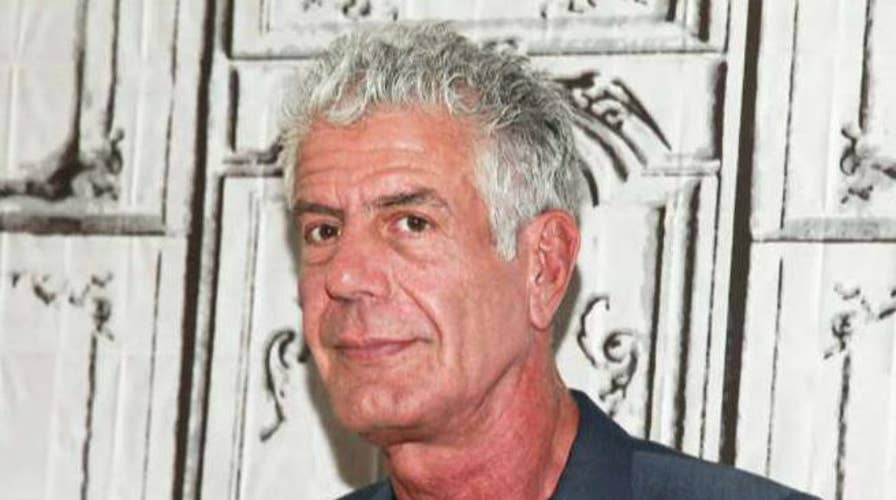

As someone who once nearly committed suicide – going as far as holding a gun to my head – I was saddened, but not shocked, by the suicides of celebrity chef and CNN host Anthony Bourdain and fashion designer Kate Spade this week.

I now speak with individuals around the globe who are considering taking their own lives. I have learned no one is immune. It doesn’t matter how much money, power, wealth or fame you have.

Anyone is a candidate for suicide, even if you’ve never had history of mental illness. At some point in life, just about all of us will reach a place where we feel like there is no escape other than death. The question becomes, what decision will we make?

For the millions of women who sport her iconic namesake handbags and accessories, Kate Spade’s death Tuesday was counter to the playful and colorful image of her brand. This very fact may have contributed to her death.

According to Spade’s sister, the designer suffered from depression for many years – yet never sought help because she felt it would reflect poorly on her personal image.

Unfortunately, Spade and Bourdain are not the first – nor will they be the last – who feel the only viable option to ending their problems is ending their life. They are not the exception; rather, they are the rule.

Their choice is a tragedy, just as was the choice to commit suicide made by Robin Williams, Alexander McQueen, Chris Cornell and countless others whose names are not widely recognized but who were loved by many family members and friends during their lives.

Suicide rates are on the rise. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Thursday that from 1999 to 2016 the suicide rate in the United States rose 28 percent – and said that in 2016 nearly 45,000 people killed themselves across our nation. That’s over twice as many people who were killed in homicides.

And the sad truth is that suicides will continue until we treat mental illness like any other illness.

Depression, mental illness and suicide are our nation’s Scarlet A. Our culture is not one where we can have open and honest dialogue, and we are not in a place where we can treat mental illness the same way as other diseases.

When someone is diagnosed with cancer, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, lupus or a long list of other illnesses, friends rally around. But learning of mental illness can push people away.

There is a stigma attached to mental health issues and suicidal tendencies. Very few of us will ever admit we are struggling because of the fear of how we will be perceived.

We ask ourselves painful questions: What will people think? Will I lose my job? Will people I love walk out on me? Will they think I’m too weak to handle the ups and downs of life? Will they call me “crazy” and say I somehow brought my illness on myself?

These are all things that stand in the way of transparency and stop people from seeking the help they so desperately need.

I’ve been on both the giving and receiving end of this. When my wife and I began counseling, we wouldn’t even tell our own family members because we were afraid of what they would think.

On the flip side, I had a friend openly tell me about his financial and marital problems. Yet he never said things were so bad that he was considering taking his own life. A week later, he committed suicide.

I kept the weight of guilt of this interaction with me for a long time, wondering what I could have done. I believe my friend reached out in the hope that, because of my own background, I would perceive that he was thinking about suicide. But I did not.

I wish my friend had realized that I welcomed the opportunity to speak about his true feelings. I wish he had realized I wasn’t going to judge, but rather that I was going to wrap my arms around him and help him find another way to deal with the situation.

While my friend made his choice and I can no longer help him, I have learned from this awful experience. The next time a friend reaches out, I will start the discussion, even if my hurting friend does not.

The leading deterrent to today’s growing suicide epidemic is dialogue. We must create open spaces for this to happen – without stigma – so we can stop the next tragic suicide.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).