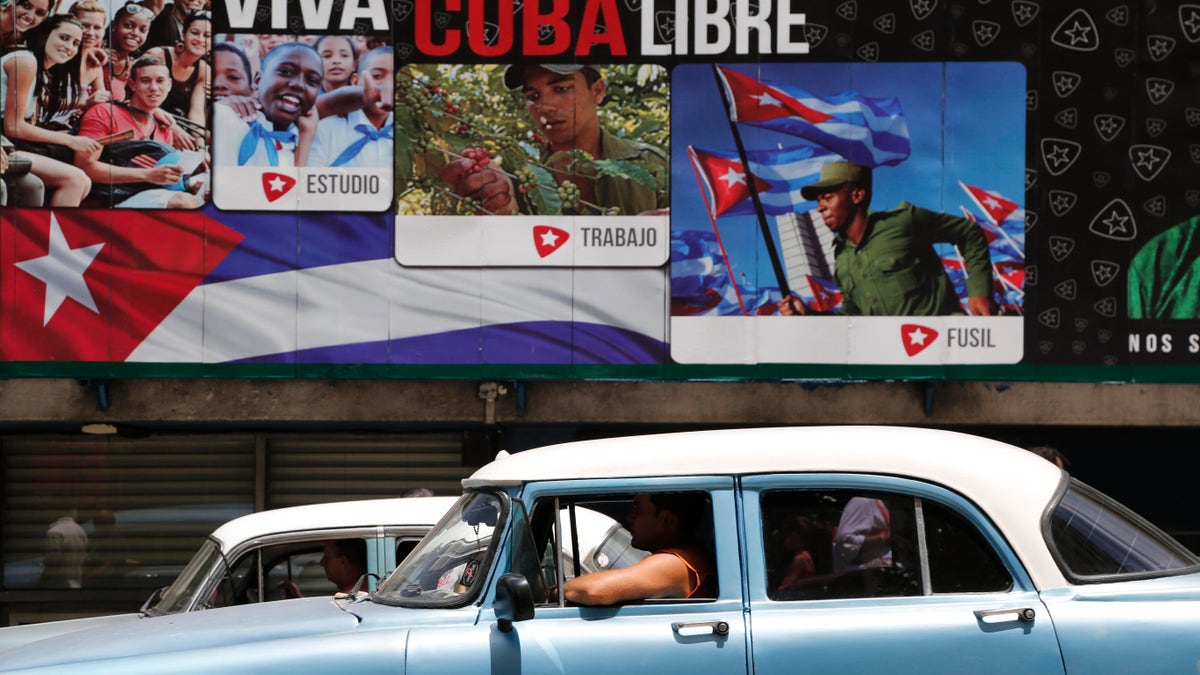

Un auto clásico estadounidense pasa frente a carteles que dicen "Viva Cuba libre" en La Habana, Cuba, el martes 16 de junio de 2015. El miércoles se cumplen seis meses desde que los presidentes Barack Obama y Raúl Castro sorprendieron al mundo al anunciar el fin de medio siglo de hostilidades entre Estados Unidos y Cuba. En Cuba, los envejecidos líderes temen un cambio rápido e incontrolado que les cueste el poder y pueda provocar inestabilidad en un país que teme a la violencia y la desigualdad que afectan a sus vecinos. Ese temor se ve acrecentado por la larga historia de intentos estadounidenses de derrocar a Castro y a su hermano Fidel. (AP Foto/Desmond Boylan)

"A year ago, it might have seemed impossible that the United States would once again be raising our flag, the stars and stripes, over an embassy in Havana," President Obama declared when he announced that Cuba and the United States would establish full diplomatic relations on July 20. "This is what change looks like."

The reopening of embassies in Washington and Havana is symbolic of the change in U.S. policy that President Obama announced on December 17 of last year—replacing the policy hostility and subversion dating back to the break in diplomatic relations 54 years ago with a new a policy of engagement and cooperation.

Having full embassies will create better channels of communication between the two governments, facilitating negotiations on all the other issues that must be resolved before bilateral relation are fully normal.

The policy of hostility persisted through ten U.S. presidential administrations. Even after the end of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the cold war in the Caribbean continued, gradually isolating the United States from our allies in Latin America, and seriously endangering U.S. relations with the entire region. It was no coincidence that in President Obama's announcement, he noted that the new approach to Cuba would also "begin a new chapter with our neighbors in the Americas."

Beyond symbolism, reopening the embassies has important practical benefits. Cuba and the United States have had diplomatic representation in each others capitals since 1977, when President Jimmy Carter and President Fidel Castro agreed to open "Interests Sections"— diplomatic missions attached to the Swiss embassy. Those missions served important functions, but were restricted in their operations. Having full embassies will create better channels of communication between the two governments, facilitating negotiations on all the other issues that must be resolved before bilateral relation are fully normal.

Another important benefit is allowing diplomats greater freedom to travel and speak with citizens of the host country. The main reason it took six months to conclude negotiations on opening the embassies was Cuban concern that U.S. diplomats would travel around the island promoting opposition to the Cuban government—a common practice during George W. Bush's administration. Diplomatic travel has been restricted to the capital regions of both countries since 2003. The United States has insisted that its diplomats have the right to travel, as specified in the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. The two sides finally reached a compromise on that contentious issue, meeting an essential U.S. condition for moving forward. Without going into detail, a senior State Department official said, "travel by our diplomats will be much, much more free and flexible than it is now."

- Rubio vows to oppose Cuba ambassador unless island agrees to concessions

- Obama’s inaugural poet, Blanco, launches project to lift Cuba’s ’emotional embargo’

- Florida Straits becomes ‘Wild West’ as Cubans flee island and head to U.S.

- Sen. Menendez keeps himself busy, vocal as he awaits ruling on trial location

- As relations ease, Cuba demands return of ‘illegally occupied’ Guantanamo Base

- Puerto Rico calls in National Guard to help island deal with severe drought

- Cubans take U.S. journalism classes, risking harassment and even arrest

- Cuba first country to end mother-to-infant transmission of HIV and syphilis

- Obama administration close to announcing opening of embassy in Cuba, sources say

- Travelers flock to Cuba before American invasion

- Life’s A Beach In Cuba

- Want the real Cuba? Try Havana Vieja

Congressional opponents of President Obama's opening to Cuba can do nothing to stop the re-establishment of relations. The Constitution vests the power to recognize foreign countries with the president alone. But whoever the president nominates as the new U.S. ambassador to Cuba will face tough sledding in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee where Senators Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Robert Menendez (D-NJ) have declared unwavering opposition to normalizing relations. In the House of Representatives, Republicans have introduced legislation to deny funds to upgrade the Interests Section to a full embassy—a move that only punishes U.S. diplomats in Havana, prospective Cuban immigrants, and visiting and U.S. citizens who need consular services.

Echoing their party's presidential contenders, Republican leaders in Congress are promoting the narrative that Obama is weak on foreign policy, from Syria, to Ukraine, Iran, and Cuba. They will not allow any legislation in the next 18 months that would make Obama's Cuba policy look like a success. That means U.S. economic sanctions—the embargo and ban on tourist travel—will remain in place at least through the next presidential election since lifting them requires changing the law.

Nevertheless, there is more that can be done. Washington and Havana have a half dozen working groups of diplomats discussing a wide range of topics. We could soon see bilateral agreements on issues of mutual interest like law enforcement cooperation, counter-narcotics cooperation, environmental protection in the Caribbean, the restoration of postal service, and more.

President Obama could use his licensing authority to further expand commerce with Cuba, in particular, licensing U.S. banks to clear dollar-denominated international banking transactions involving Cuba, a prohibition that is today one of the major impediments to Cuba's international commerce with the West. The president could restructure democracy promotion programs so that they support authentic exchanges in education, the arts, and culture, rather than promoting opposition to the Cuban government.

The issues between the United States and Cuban are complex and multi-faceted. Resolving them will require overcoming half century of mutual distrust. But the re-establishment of normal diplomatic relations constitutes the first necessary step toward the future. As Raúl Castro said during his meeting with President Obama at the Seventh Summit of the Americas in Panama last April, "Our countries have a long and complicated history, but we are willing to make progress.... We are willing to discuss everything, but we need to be patient — very patient."