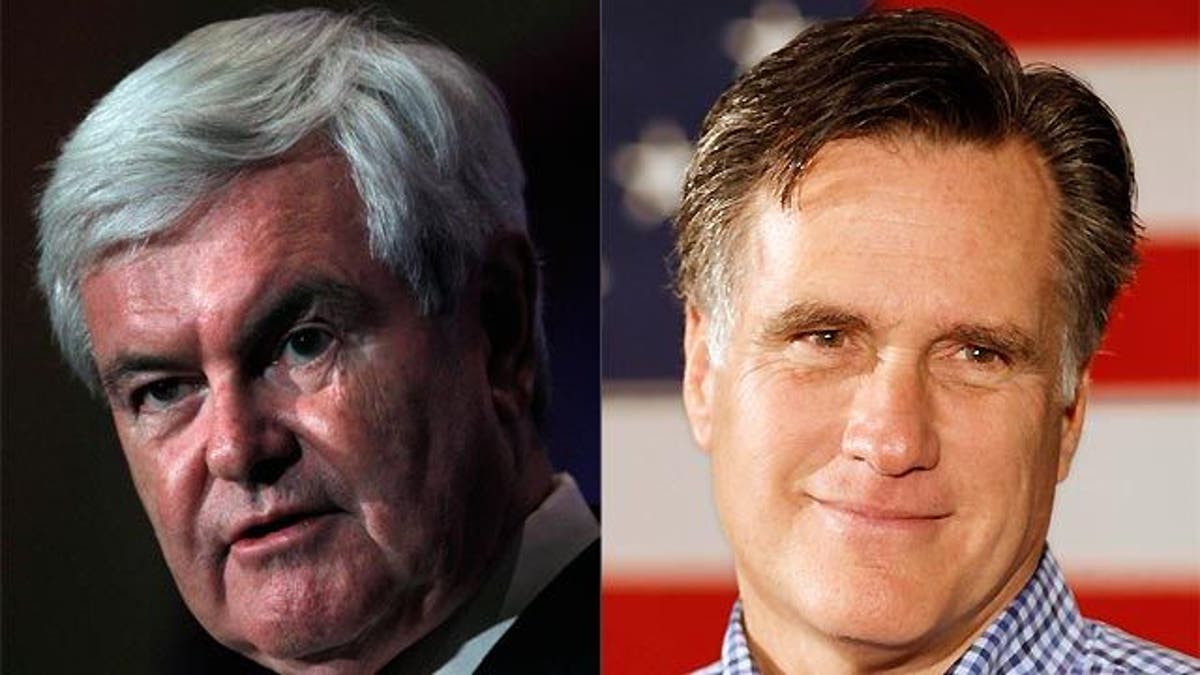

Wednesday afternoon Newt Gingrich is expected to announce that he will suspend his presidential campaign. After yo-yoing from the bottom of the heap to the top of the pack and back down to the bottom again, his time to win delegates and the opportunity to raise money both have finally ran out.

There is an overwhelming temptation among many in the world of political commentary to dismiss this news as the inevitable prevailing over the impossible. “Newt never stood a chance against Romney. He had no money, no organization, no institutional support” likely summarizes the conventional wisdom about the end of his short-circuited campaign.

However, Gingrich is hardly a victim. As has been the case throughout the year, he makes it easy for his critics to marginalize and lampoon him, mainly because his ego is considered as “big” as his ideas.

Take Wednesday’s announcement as an example. The Gingrich campaign attempted to generate massive build up around an event that essentially features the former House Speaker dropping out of the race.

Few outside Gingrich's intimate group of family and advisers think his speech today, focused on "the important role citizens can play in stopping a second Obama term and helping Mitt Romney and the Republican Party build a governing coalition in Washington”; will ultimately have any impact on the race. So what justifies such a prolonged exit from the political stage?

Wednesday's announcement is another illustrations of why Newt stands to end this campaign with fewer friends than he started it with. He leaves the race with an overwhelming impression that his ego was the largest determining variable in his campaign strategy. What he did on the campaign trail was not governed by what was in the best interest of the process, the country or loyalty to core conservative principles.

But to simply limit the review of Gingrich's campaign’s efforts to that perspective misses a much bigger point, since a good argument can be made that Newt Gingrich was the candidate who mainly strengthened Mitt Romney, much the way that Hillary Clinton did for Barack Obama in 2008. And by those lights, that would make Gingrich the most consequential candidate of the 2012 primary cycle -- other than Romney himself.

Gingrich ultimately eclipsed other challengers including Rick Perry, Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, Ron Paul and Jon Huntsman based on one major measure: did their candidacy make the eventual nominee stronger and with that boost the GOP’s chances to recapture the White House? Rick Santorum can claim to have given Romney the fiercest challenge in the delegate race, but it was Gingrich who delivered the transformational moments for Romney to emerge in a better position to defeat President Obama in November.

Here are some of Gingrich's three biggest contributions to Romney's candidacy:

1) Gingrich forced Romney to bring his “A” game to the debates: After Gingrich's dominant win in South Carolina (which was largely driven by superb debate appearances), Romney was in a must-win situation in Florida.

Romney’s performance in the Jacksonville, Fla. debate was a turning point in which he completely neutralized Gingrich and demonstrated an ability to be a fighter, not just a fixer.

He also needed to show Republican voters he could take on another skillful debater -- President Obama.

He succeeded on both counts.

2) Gingrich gave Romney the opportunity to respond early to the attacks on his work at Bain Capital: Attacking Romney for his successful career in the financial services industry was a huge misstep for a candidate whose party offers the free-market as the alternative to government for solutions. This gave Romney some unexpected “batting practice” to manage this much more predictable attack line from the Obama campaign. It also forced Romney to address questions about his vast wealth, a topic that he is still struggling with but has managed to tackle more effectively since the Gingrich attacks.

3) Gingrich allowed Romney to reinforce his conservative bona fides using the immigration issue: Eager to prove his conservative credentials Romney was able to use Gingrich’s more establishment Republican position on the immigration issue to show that he held a view more in-line with those in the conservative grassroots.

Ironically, Gingrich also afforded Romney a duel advantage on this issue when he attacked him in a debate suggesting his policies would end up deporting grandparents.

Romney replied, “Our problem is not 11 million grandmothers,” a response that made him seem more reasonable about the issue.

But this issue was effectively used by Romney as a counterweight in a primary heavily-populated by conservatives.

A year ago I wrote a less than flattering opinion piece suggesting Newt Gingrich’s presidential campaign was essentially a non-starter. Luckily for Mitt Romney, it lasted long enough to make him a stronger candidate to challenge President Obama in the general election.

Tony Sayegh is a Republican campaign consultant, political analyst and National Political Correspondent for Talk Radio News Service. You can e-mail Tony at tony4ny@yahoo.com.