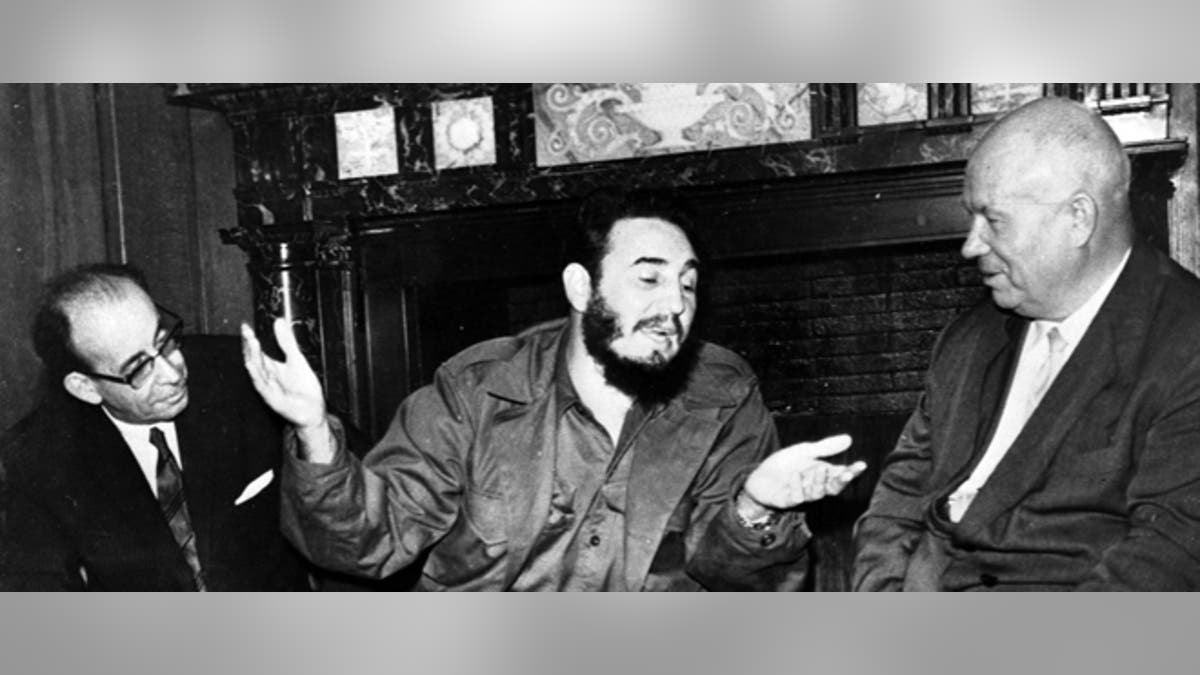

In this Sept. 20, 1960 photo, Cuba's leader Fidel Castro, center, speaks with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, right, as his Foreign Minister Raul Roa, left, looks on at the Hotel Theresa during the United Nations General Assembly in New York. The world stood at the brink of Armageddon for 13 days in October 1962 when President John F. Kennedy drew a symbolic line in the Atlantic and warned of dire consequences if Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev dared to cross it. On the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis, historians now say it was behind-the-scenes compromise rather than a high-stakes game of chicken that resolved the faceoff, that both Washington and Moscow wound up winners and that the crisis lasted far longer than 13 days. (AP Photo/Prensa Latina via AP Images) ((AP Photo/Prensa Latina via AP Images))

There’s something very wrong with the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. How could such a defining event of The Modern Age – aerial photography! televised addresses! ICBMS! split-second global consequences! the quintessential twentieth century presidency! – so suddenly have acquired, with nary a warning, all the trappings of antiquity?

Last week, milestone looming, I asked a two-person research team at Fox News to locate surviving members of the Kennedy administration who might have played some role in the Cuban Missile Crisis. The researchers, highly skilled, came back with a list of six men and one woman – the latter a White House secretary.

The youngest, at 75, is already quite familiar to Fox News viewers: our ace military analyst, Lt. Gen. Thomas McInerney (USAF – ret.), who flew escort reconnaissance missions over Cuba during the crisis.

Another on the list, John William Peterson, now eighty-one, stood watch on U.S.S. Beale, the destroyer that participated in the naval blockade of Cuba.

[pullquote]

Tens of thousands of fighting men sprang into action because of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Soviets alone sent 40,000 men to Cuba, on eighty vessels, to unpack and operationalize all the missiles and warheads.

Thousands of uniformed Americans, apprised of the installation of Soviet missiles on an island ninety miles from US soil, flew extra air drills, conducted naval maneuvers, loaded bombs, monitored radar, tracked Russian submarines, boarded Jeeps at night, pulled double shifts, relocated their families, and otherwise coped with the ultimate Modern Nightmare: the prospect of imminent nuclear war.

“We came damn close,” said Dino A. Brugioni, perhaps the last surviving veteran of the high-stakes meetings on the crisis in the Kennedy White House. Now ninety, Brugioni served in October 1962 as a senior official at the National Photographic Interpretation Center, a branch of the Central Intelligence Agency. It was his boss, CIA official Arthur Lundahl, who led Kennedy’s first briefing on the matter.

Brugioni’s job back then included preparing the large reproductions of the aerial reconnaissance photographs that revealed the Soviet missiles, and their various supporting structures, arrayed in the Cuban jungle with absurd geometric orderliness.

These are the iconic images of the crisis: those strangely placid black-and-white jungle shots, overlain with pointing lines and white signs that said, in serif-less early-Sixties font, inscrutable things like MISSILE ERECTOR and OXIDIZER TANK TRAILERS. These were the images that stunned the president and Bobby and McNamara and Rusk and the Joint Chiefs – and that helped them navigate the crisis.

Brugioni published his highly regarded memoir, "Eyeball to Eyeball: The Inside Story of the Cuban Missile Crisis," in 1992.

When I talked with him by phone, he sounded talkative and animated, fastidious about facts, eager to educate a younger man about the direness of the great event.

As an aside, he mentioned having flown 66 bombing missions in World War II. He was highly decorated before joining CIA in 1948 and served there until 1980.

The fiftieth anniversary found Brugioni busier than ever, leading a slide presentation of nearly 100 images at the Smithsonian, sitting for interviews with cable channels, lecturing. He even gave me his e-mail address.

Also on the list was Ralph Dungan, whom I tracked down in Barbados through his daughter in Wisconsin. Feisty and acerbic, a charmer at 89, Dungan was one of nine men, alongside the likes of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and Lawrence F. O’Brien, who held the title of Special Assistant to the President during Camelot; after Kennedy was cut down by an assassin’s bullet, Dungan served three years, under LBJ, as U.S. ambassador to Chile.

He had first gotten to know Jack Kennedy during the latter’s Senate days, through speechwriter Ted Sorenson. Initially, as Dungan once recalled, he was recruited to serve as “Kennedy’s spy” on the Government Operations Committee. Once in the White House, Dungan moved into the empty West Wing office – everyone else thought it was irreparably tainted, and refused to occupy it – that had formerly belonged to Sherman Adams, the disgraced chief of staff to President Eisenhower.

Dungan, too, it seemed, was eager to recall the missile crisis, even as he acknowledged that he had had nothing to do with it, professionally. “It was the most important event that occurred in the Kennedy administration,” he told me. “You had two guys, Kennedy and [Soviet Premier Nikita] Khrushchev, who were really politicians to the core. And whatever informed them, both wanted to avoid a nuclear war.”

Of the youthful president, Dungan said: “I knew him well enough to know how his mind worked. And anybody who could’ve stood up to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and all his civilian advisers in the Cabinet, and the Congress, too – all of whom were advising him to do the wrong thing – gets very high marks from me.” He, too, gave me his e-mail address.

Dan H. Fenn, also eighty-nine, still teaches at Harvard University. Fenn was serving on the faculty of the Harvard Business School when he was tapped, in 1961, to work as a staff recruiter at the White House. His place within the Kennedy orbit grew over time, such that he was named, in 1972, as the first director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Fenn, like Dungan, will tell you up front he didn’t work on the crisis; but he remembers well the tension that gripped Washington in the days leading up to the disclosure of the missiles on Cuba – people knew something big was happening, but not what, exactly – and then deepened as the crisis unfolded. “There were only 77 people in the entire Kennedy White House back then,” he told me. “I would see [Kennedy] all the time, just walking in the hallway. People thought nothing of it if I exchanged a few thoughts with him.”

Like the others I contacted, Fenn has participated in numerous oral history programs, conducting lengthy recorded interviews with trained historians about his time in Camelot. He’s got one more ahead of him: when Dan Fenn joins me live, from the Harvard University campus, in “The Foxhole,” my online show that airs Friday at 4 pm ET at live.foxnews.com.

And on-set with me, live in our Washington bureau, will be David G. Coleman, the Cold War historian and professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center who’s just published "The Fourteenth Day: JFK and the Aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis/The Secret Tapes" (W.W. Norton & Company, 2012). The book examines how President Kennedy and the National Security Council confronted the vital questions that persisted even after the crisis had supposedly abated, on October 29, 1962: its thirteenth day. How to verify that both superpowers would faithfully execute the agreements they had negotiated to end the crisis; how to ensure their respective technicians would safely disassemble the weapons at the heart of the affair, capable of destroying whole cities – these were among the issues policymakers wrestled with as the midterm elections of 1962 approached.

For research, "The Fourteenth Day" draws extensively on the 257 hours of recordings Kennedy made as president, including many previously unheard segments that Coleman was the first to transcribe.

We’ll play some of those “new” Kennedy tapes on the program. We’ve married the snatches of audio to transcripts you’ll be able to read along with, while seeing photographs of the people doing the talking.

You’ll also be able to join our live chat and pose your own questions through your Twitter or Facebook account. It’s all very high-tech, state-of-the-art stuff: the very essence of The Modern Age.

James Rosen is Fox News chief Washington correspondent and author of The Strong Man: John Mitchell and the Secrets of Watergate. @JamesRosenFNC