Progressives believe that only government professionals can shape the modern economy to the benefit of the greatest number of people.

President Obama believes this. His State of the Union address called for more federal government minding of the nation’s business while his steady stream of unilateral ObamaCare edicts shows a distain for the role of the people’s representatives in Congress.

[pullquote]

The idea that the president doesn’t need to work with Congress has its modern origins in Woodrow Wilson’s robust progressivism.

Wilson sought to remake the federal government at the expense of the Constitution and its separation of powers. The Constitution was a relic in his eyes, not up to the challenges of an industrialized nation.

In Wilson’s ideal, elected politicians were to enact broad, sweeping laws, the details of which would be hammered out and implemented by professional bureaucrats.

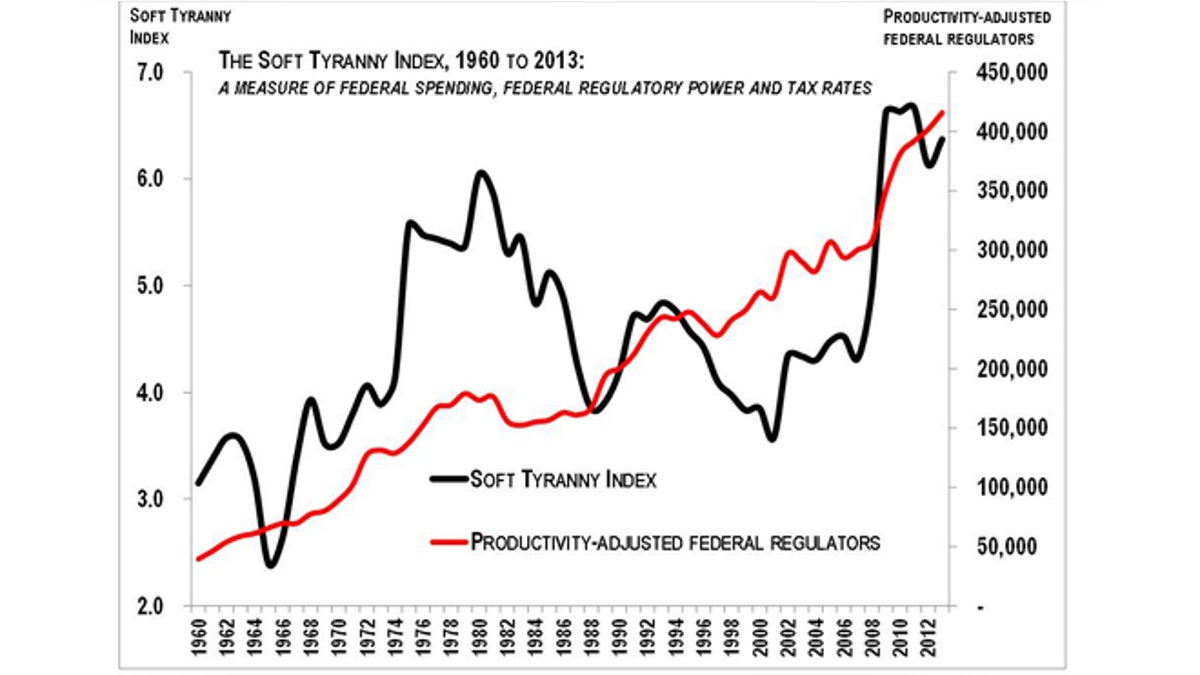

By 1960, half a century after Wilson’s expansion of federal power, some 40,000 regulators worked for the federal government.

By 2013, the regulatory workforce expanded to almost 140,000, a three-fold increase.

Like a glacier moving slowly to the sea, the advances of bureaucratic power are incremental and ceaseless. Further, due to increased outsourcing and massive increases in workforce productivity, federal regulators are far more powerful today than suggested by the mere increase in their ranks.

Outsourcing has slowed the growth of federal workers with some 7.5 million federal contractors supporting a federal civilian workforce of 2.1 million. Much of this contractor support force is in blue collar and support functions, freeing up federal workers for more important tasks. But a Harvard-trained lawyer working in the antitrust division at the Department of Justice can affect liberty and the operation of free markets far more than can a federal worker armed with a mop and bucket.

Productivity is the other large driver of regulatory strength. Productivity advances, especially in information technology, have made federal workers far more potent. But conservatives who view “government efficiency” an oxymoron aren’t likely to give the bureaucracy credit for being more efficient while liberals who support government employee unions have little incentive to point out that the government workforce can do more with less. Accounting for productivity advances, the federal regulatory cadre is some 11 times more powerful today than in 1960.

This bureaucratic “productivity” means more rules. In the early 1960s, the Federal Register, the publication in which all new federal regulations are published, averaged less than 14,000 pages per year. Today’s Federal Register can run more than 80,000 pages.

This avalanche of new rules comes at a price. The Competitive Enterprise Institute has estimated that the annual cost of federal rules compliance is greater than the total of individual income taxes and corporate income taxes.

The mounting cost of regulations has another dimension: American liberty is eroded when unelected bureaucrats are empowered by Congress and the President to make rules that the nation must live under.

Alexis de Tocqueville warned that the threat to American democracy wasn’t direct or hard tyranny; rather, it was soft tyranny, driven by good intent. Tocqueville wrote in 1835’s Democracy in America about “…a network of small complicated rules…” acting to reduce citizens to sheep with the government their “shepherd.”

A more contemporary observer of the American scene, the late U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-Minn.) said in 1979, “The only thing that saves us from the bureaucracy is inefficiency. An efficient bureaucracy is the greatest threat to liberty.” The Code of Federal Regulations contained about 30,000 rules then. Today, the federal government has more than 180,000 rules.

Beyond regulators and the rules they write, the federal government has other ways of shaping our economy: the tax code with its tax rates as well as federal spending.

Taxes can have a huge impact on the business decisions while government spending lays claim to goods and services that would otherwise be consumed by individuals making free choices.

Fortunately, these four things—regulators, rules, tax rates, and federal spending—can be tracked objectively over time to create a Soft Tyranny Index. This Soft Tyranny Index shows that America has experienced two significant peaks of federal meddling in our economic life: in the decade of the 1970s peaking in 1980 and since 2007, with all-time highs being reached during the current administration.

Encouragingly, the index shows that soft tyranny at the federal level isn’t inevitable—there was a period of extended retreat in the index from 1981 to 1988 under President Reagan’s tenure and again after the 1994 takeover of Congress by Republicans.

Lastly, the principles of the Soft Tyranny Index can be applied to the states to objectively compare government power. Texas and South Dakota have the smallest government footprint while New York and California have the largest.

Government interference in the economy leads to less growth. The 10 freest states saw an average of 22.5 percent growth in real private GDP from 2002 to 2012 during a time with the private U.S. economy expanded 18 percent. But the 10 states with the greatest soft tyranny averaged only 13.7 percent growth. The 10 states with the most liberty generated 64 percent more private economic growth than the 10 big government states.

The lesson: less government fosters liberty and prosperity.