In the past, the opening days of contested conventions typically featured test votes so factions could see how strong each contender was. These test votes frequently centered on the selection of the temporary chairman, elected immediately after the party chairman called the convention to order.

The temporary chairman had real power – appointing leaders of the committees that considered credentials challenges, set the rules, recommended the meeting’s permanent officers, and wrote the platform. But his time at the podium was limited, being replaced by a permanent chairman, elected generally on the second day.

The June 1884 GOP convention in Chicago opened with Republicans badly split. On one side were those who supported the nomination of President Chester A. Arthur, who had succeeded to the office upon President James Garfield’s assassination. But most delegates were leery of the New York machine politician, believing his reputation for patronage and boodle was too unsavory.

Arthur’s leading challenger was James G. Blaine, Garfield’s secretary of state, but he was one of nearly half-a-dozen possible alternatives to the incumbent, none of whom had enough votes to win on the first ballot.

The convention was held at Chicago’s Exposition Center on Lake Michigan, a 1,000-feet long and 200-feet wide structure, topped by a dome. It was painted a dull Indian red that vividly contrasted with the sky and white clouds visible through 200-foot tall arched glass windows on its long east and west sides. The podium was in the hall’s east, decorated in Union battle flags. Portraits of Washington, Lincoln and Garfield hung over the stage.

After the convention was gaveled to order at 12:28 P.M. on Tuesday, June 3, the Republican National Committee offered Powell Clayton for temporary chairman. The tall, blond-haired, blue-eyed, one-armed Union veteran from Kansas had settled in Arkansas after the Civil War and was elected governor in 1868 and U.S. Senator in 1871. By 1884, he was out of office but as leader of the “Minstrels” faction, still boss of the Arkansas GOP.

Some anti-Arthur men wanted Clayton as temporary chairman to embarrass the president. Clayton had supported until Arthur rejected his demand to be appointed Postmaster General with control of the Post Office’s vast patronage.

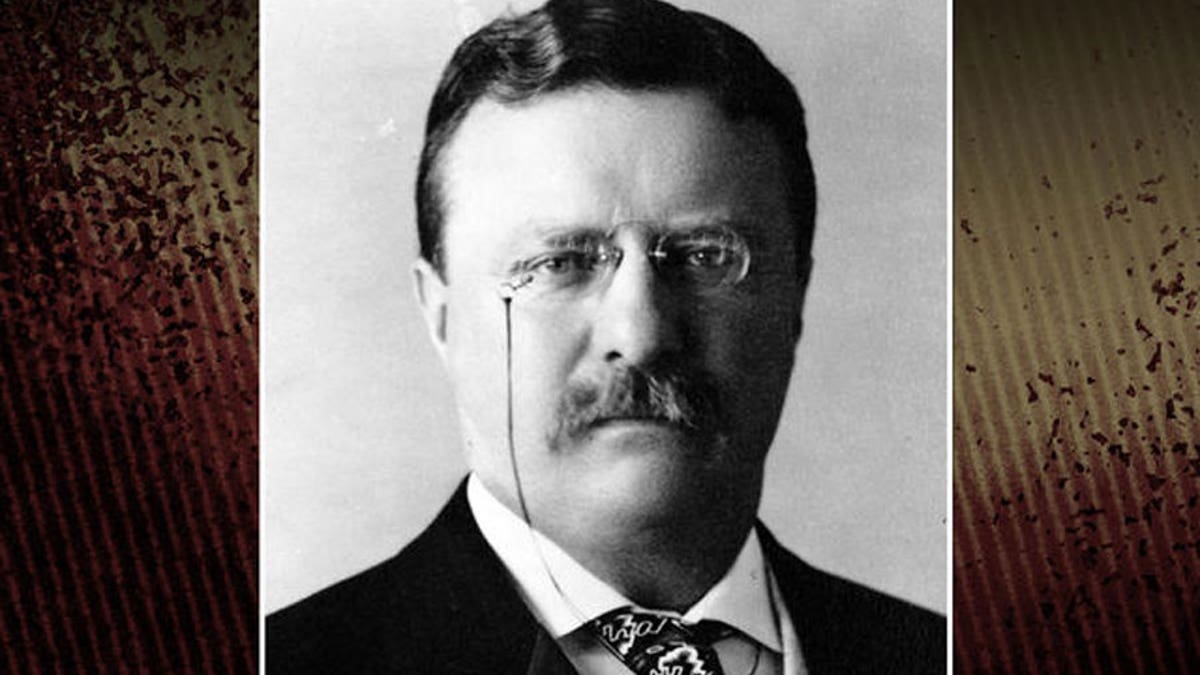

But the idea of rebuking one machine politician – Arthur – by electing another machine man – Clayton – was too much for two young Eastern reform Republicans. One was the 34-year old Massachusetts GOP state chairman, the other a 25-year old New York Assemblyman from a silk stock Manhattan district. They had met briefly a year or two before in Boston and exchanged stilted formal letters shortly before the convention. They were drawn together by their mutual support for Vermont Sen. George Edmunds, a favorite of Easterners bent on fundamental reform of their party, so it didn’t help their opinion of Powell that he backed Blaine.

When Powell was nominated, the Bay Stater immediately rose, gained the chair’s recognition and moved to substitute John R. Lynch of Mississippi in place of Powell. The Blaine men were caught by surprise, having expected a united anti-Arthur front on the question of the temporary chairman.

Lynch’s nomination presented a special problem for them. The Blaine men were counting on southern Black Republicans to help secure their man’s nomination. But Lynch was a former slave, freed at the age of 16 in 1863 by the Union Army. Lynch entered politics after the Civil War, serving in the State House of Representatives from Natchez and being elected Speaker in his last term, the first Black to hold the position. Lynch then served two terms in the U.S. Congress from 1873 to 1877, and then was reelected in 1880 for a single term. If Black delegates voted for Lynch, they might get into the habit of making surprises.

In response to Lynch’s nomination, several party bigwigs condemned the substitute nomination as an attack on tradition, some making the argument that defeating a decorated veteran would be an insult. In response, the young New York Assemblyman reminded delegates that 24 years before, Republicans had chosen Abraham Lincoln “who broke the fetters of the slave and rent them asunder forever” and called it “fitting…to choose to preside over this Convention one of that race whose right to sit within this walls” was due to the victory made possible by Lincoln’s leadership.

After more wrangling, the previous question was called and the roll began. When it was over, Lynch beat Clayton, 431 to 387, becoming the first Black man to chair a national convention of any major political party.

His victory also cemented the friendship of the two young troublemakers – Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts and Theodore Roosevelt of New York.