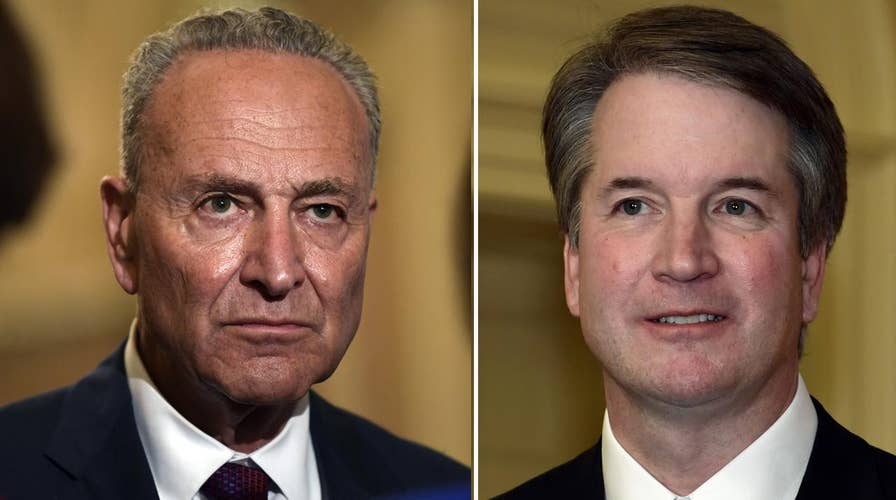

Napolitano: Can Chuck Schumer's anti-Kavanaugh crusade work?

Freedom Watch: Judge Andrew Napolitano and Juan Williams discuss Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer's scorched-Earth policy against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and whether or not it can work.

Senate Democrats – obsessed with opposing everything President Trump does – are making the absurd claim that the president nominated Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court to protect himself from the Russia probe being conducted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said that the president believes Kavanaugh can provide him with a “barrier to preventing that investigation” by Mueller of Russian interference in our 2016 presidential election and possible obstruction of justice or other misconduct by Trump and people working for him.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J. agrees with Schumer. Booker said that President Trump “picked the one guy who has specifically written that a president should not be the subject of a criminal investigation, which the president is right now.”

The anti-Trump media have picked up the theme. Vox’s Ezra Klein writes: “Kavanaugh was the right pick if Trump’s top priority was protecting himself from criminal investigation.”

This accusation has no factual basis. In fact, it is an outright lie.

Schumer and Booker are deliberately misrepresenting and distorting an article that Kavanaugh – currently serving on the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia – wrote in the Minnesota Law Review in 2009. The article by the judge says the exact opposite of what Schumer and Booker falsely claim it says.

Schumer and Booker are deliberately misrepresenting and distorting an article that Kavanaugh – wrote in the Minnesota Law Review in 2009. The article by the judge says the exact opposite of what Schumer and Booker falsely claim it says.

Writing in his law review article with no perceptible political bias or agenda, Kavanaugh reviewed several important challenges to the country’s governmental institutions that had arisen in the Clinton and Bush administrations.

Kavanaugh wrote that he had observed the truly extraordinary difficulty of the presidency first-hand from years of service in the George W. Bush White House. The burdens of the presidency were, he found, far more daunting than he had expected in the 1980s and 1990s.

President Donald Trump shakes hands with Judge Brett Kavanaugh his Supreme Court nominee, in the East Room of the White House, Monday, July 9, 2018, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon) (Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

Yet sitting presidents were also expected to assume the risks and burdens of being entangled in litigation, both civil and criminal. And those risks and burdens were substantial – so much so, that they could prevent the president from focusing on problems of far greater importance for the country as a whole, Kavanaugh wrote.

“Looking back into the late 1990s,” Kavanaugh wrote in his Minnesota Law Review article, “the nation certainly would have been better off if President Clinton could have focused on Osama bin Laden without being distracted by the Paula Jones sexual harassment case and its criminal investigation offshoots.”

Coming from a former member of the legal team that had investigated President Clinton, this was a startling statement. It was also clearly true. And most Democrats, both at the time of that investigation and in 2009, would surely have agreed with Kavanaugh. Surely, Bill and Hillary Clinton would have agreed.

Kavanaugh clearly did not – repeat, not –argue in his law review article that the president has a constitutional immunity from being investigated or sued. Nor did he claim that misdeeds by a president should never subject the president to an accounting before the law. Kavanaugh explicitly affirmed that all of us – including the president – are equal in the eyes of the law.

Kavanaugh clearly did not argue in his law review article that the president has a constitutional immunity from being investigated or sued.

Kavanaugh merely proposed that Congress should enact a law temporarily barring civil and criminal suits against a president while in office.

Lawsuits against a president, Kavanaugh advised in his article, should be deferred – much as Congress has deferred lawsuits against certain members of the military.

You don’t have to be legal scholar to understand this. Just think logically: If Congress can reasonably find that the duties of a military officer require protection for that officer from being sued while in the military, surely it would be reasonable to extend the same kind of protection to the president.

The president, after all, has vastly greater responsibilities than any military officer – including being commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces.

And here’s the most important thing to understand about Kavanaugh law review article: His proposal would make absolutely no sense if he believed that the Constitution already made the president immune from lawsuits. There would be no reason to pass a law giving the president protection already provided by the Constitution.

In fact, Kavanaugh specifically noted that the Supreme Court’s decision in Clinton v. Jones – which held that President Clinton was not constitutionally entitled to the deferral of Paula Jones’ civil lawsuit while he was in office – “may well have been entirely correct.”

Kavanaugh did not question – let alone recommend reversing – the Clinton v. Jones ruling. He recommended working within its parameters, which allow Congress to legislate a temporary immunity, valid only for the president’s term.

Kavanaugh’s recommendation regarding civil actions was squarely in the mainstream of informed opinion. Cass Sunstein, one of the nation’s leading liberal legal scholars, argued in 1999 that although the Clinton v. Jones decision was legally correct, it was also “disastrous and obtuse.”

And Sunstein recommended a remedy identical to the one Kavanaugh would propose a decade later: “Congress should, it seems to me, pass a law saying that while the President is in office, he or she cannot be subject to civil actions, but the statute of limitations is not going to bar suits that are brought the day after he or she leaves. That is not to protect the President. That is not our concern. It is to protect the country.”

But what about criminal – as opposed to civil – actions?

Kavanaugh would have been on solid ground if he had taken the more aggressive position for presidential immunity in this area. In Federalist 69, written to persuade Americans to ratify the draft Constitution, Alexander Hamilton observed that Congress, unlike the British Parliament, had tools to control a wayward chief executive.

“The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office,” he wrote, “and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.”

Hamilton was clear: impeachment first, prosecution second.

The Constitution’s structure only reinforces Hamilton’s argument. The Constitution vests in the president alone the duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

The framers understood this language to give the president supervisory control over all federal investigations and prosecutions. If a president wishes to prevent his own prosecution while in office, he need only order it.

Under the Constitution, the president can fire subordinates who refuse to carry out presidential orders. But the Constitution effectively requires the removal of a president, through impeachment, if he blocks his own prosecution without sufficient cause.

In short, the framers clearly established impeachment as the primary method to punish a president who commits misdeeds while in office.

If President Trump really has conspired with the Russians to violate federal law or has engaged in obstruction of justice, impeachment allows his removal by Congress for “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

Senate Democrats today support the approach of prosecuting first because they lack the personal courage, political will and popular support to press for impeachment, as the Constitution requires.

In his law review article, Kavanaugh made a moderate proposal to solve the problem of criminal investigation of a president, itself created by Congress’s unwillingness to use the ample constitutional powers at its disposal.

It is a measure of the Democrats’ desperation that they should so badly falsify Kavanaugh’s actual ideas.

Like any other Supreme Court nominees, Kavanaugh’s record should be scrutinized closely and carefully. But it should not be distorted by willful lies.