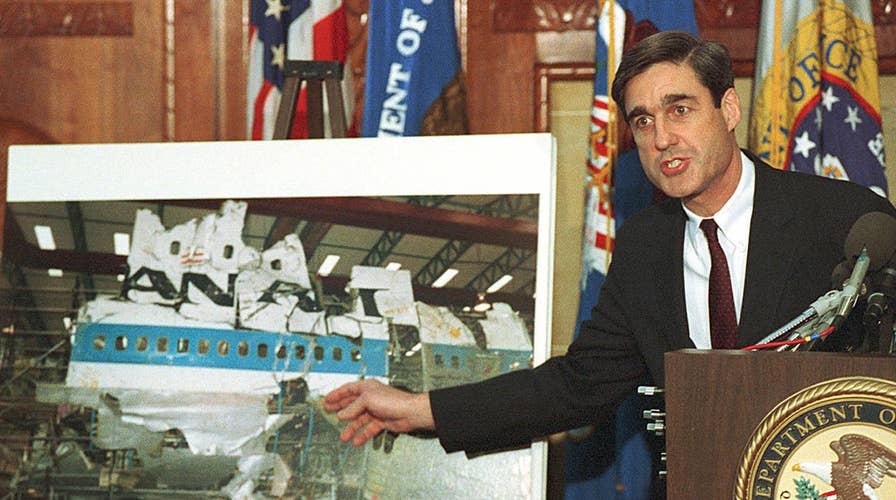

A look at Robert Mueller's career

The new special prosecutor served as FBI director from 2001 to 2013

In a rare moment of apparent consensus, Republicans and Democrats, pundits and ordinary citizens seem to be overjoyed at the appointment of a special counsel. President Trump, on the other hand, has already tweeted a dissenting view stating: “this is the single greatest witch hunt of a politician in American history!”

While I do applaud the appointment of Robert Mueller, because of his distinguished background, I also worry about the process by which the special counsel investigates its targets.

I care more about due process and civil liberties than I do about politics. As a civil libertarian, I have long opposed the way even honest prosecutors use grand juries in a manner totally inconsistent with the original intent of the Framers who wrote our Fifth Amendment that provides grand juries for all federal felonies.

The grand jury comes as close to a Star Chamber as any institution in America. It operates behind closed doors, denies targets and witnesses the right to have their counsel present, is presented only with inculpatory and not exculpatory evidence, and is supposed to decide only whether there is sufficient evidence to warrant a finding of probable cause. Grand jury proceedings are secret and we almost never know what happened within that black box. That’s why lawyers say that prosecutors can get a grand jury to indict a ham sandwich.

The rule of criminal justice is that it is better for ten guilty people to go free than for one innocent people to be convicted, but that salient rule does not apply in grand jury proceedings. The mantra of the grand jury is “when in doubt indict.”

The function of a grand jury is not to learn the historic truth. It is to learn the prosecutor’s version of the truth based on the evidence that he or she chooses to present to the grand jury. Honest prosecutors, and Robert Mueller is among the most honest, will not seek an indictment of someone they believe to be innocent.

But no system of criminal justice should have to depend on good faith and integrity of individual prosecutors. There are too many opportunists within the ranks of prosecutors, who merely seek notches on their belt rather than real justice.

The real problem with the appointment of a special counsel in this case is that the most serious allegations against the Trump administration are not criminal in nature, and are therefore beyond the scope of the special counsel’s mandate.

It would not be criminal, even if it happened, for the Trump campaign to have collaborated with the Russians in an effort to get their candidate elected. It would have been wrong but not criminal.

Nor is it a crime for President Trump to have provided classified information to the Russians that could lead the Russians to learn the sources and methods of our ally’s intelligence gathering.

Finally, it is probably not an indictable offence for the president to have fired the Director of the FBI and/or asked him to “let it go” with regard to his fired national security advisor. Just because something is wrong doesn’t make it criminal.

To be criminal there must be admissible evidence that proves beyond a reasonable doubt that a statutory crime has been committed. It is unlikely that such a conclusion will be reached by the special counsel with regard to President Trump or anyone currently in his administration. It is possible that he may find criminal conduct on the part of General Flynn, but even that is unlikely. But even if Flynn were to be indicted it is certainly possible that Trump would pardon him.

A special counsel is even more dangerous for civil liberties than ordinary prosecutors, because they generally have only one target. That target may be a person or a group of people, but there is an inclination to find criminal conduct when the focus is so narrow. A special prosecutor is like Captain Ahab and the white whale is his target. Lavrentiy Beria, the notorious former head of the Soviet KGB, once reportedly said to Stalin “show me the man, and I’ll show you the crime.”

Despite the appointment of an extraordinarily able and distinguished special counsel, civil libertarians should not be applauding the decision to employ a special counsel in this case. It would have been far better for Congress to have appointed a non-partisan investigatory commission similar to the ones appointed to investigate the 9/11 terrorist attack and the destruction of the Challenger. Such a commission would have only one goal: finding the whole truth.

A special counsel has a very different goal: deciding whether to prosecute particular individuals. At this point in our history, learning the truth may be more important than prosecuting questionable cases.