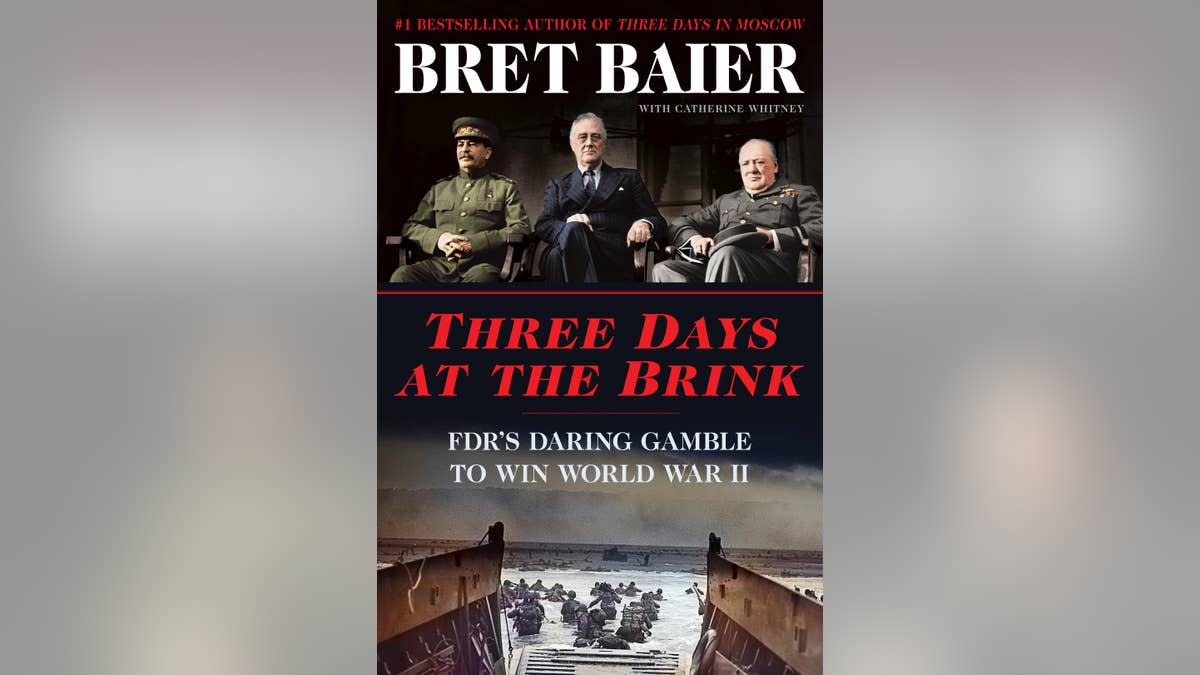

Operation Overlord — or D-Day as it came to be known — was the highest risk venture of World War II. Researching my upcoming book, "Three Days at the Brink: FDR’s Daring Gamble to Win World War II," I was struck by the drama involved in the decision to launch an invasion across the English Channel on Western Europe.

At a critical conference in Tehran in November 1943, the “Big Three” – President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Josef Stalin –fiercely debated the wisdom and timing of such a launch. They all knew it was a high-stakes gamble and that failure could lead to a catastrophic bloodbath that would turn the war in German leader Adolf Hitler’s favor. And yet, they decided it must be done.

Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was aware that, despite the peril, Overlord was a necessity.

"Every obstacle must be overcome, every inconvenience suffered and every risk run to ensure that our blow is decisive," Eisenhower wrote to his commanders. "We cannot afford to fail."

He had devised an elaborate plan, choreographed to the last detail, but he knew that some circumstances were out of his control.

On June 4, 1944, hearing discouraging weather reports and already having delayed the invasion a day because of storms, Eisenhower faced an agonizing moment of decision: to go on June 6 or wait for better weather.

When President Trump delivers his D-Day remarks Thursday at the U.S. Cemetery in Normandy, he has the rare opportunity to pay tribute with emotion, personal stories, and soaring words to the service and the sacrifice of those who died on those beaches and saved the world.

At Southwick House, the invasion headquarters in the southern English town of Portsmouth, Eisenhower sat bowed, head in hands, and contemplated a seemingly impossible choice. He wasn’t all-knowing; he could only judge circumstances as they were set before him.

Further delay might mean scrapping the mission altogether; the tides allowed only the narrowest window for invasion, and the troops were already poised. "How can you keep this invasion on the end of a limb and let it hang there?" he asked.

On the other hand, if Allied forces invaded as a storm rolled across the Channel, landing craft would be overwhelmed, air support would be impossible, and thousands could perish to no avail.

Indeed, unbeknownst to Eisenhower, German Gen. Erwin Rommel had already decided the Allies would never risk the invasion and had left the theater to meet with Hitler in Germany.

Eisenhower finally rose from his seat, unwilling to decide just yet. He suggested to his team that they try to get a few hours sleep and reconvene later.

At 3:30 a.m. on June 5, Eisenhower brought his team back together and polled them for their opinions, pacing the room as they spoke. He was heartened by an improved weather forecast.

After everyone had finished speaking, he paused, and then said, "OK, we’ll go."

The invasion was on for the following day.

FILE -- June 6, 1944: U.S. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, left, gives the order of the day to paratroopers in England prior to boarding their planes to participate in the first assault of the Normandy invasion. (U.S. Army Signal Corps via AP)

Back in his quarters, Eisenhower privately agonized over the decision. He wrote a note in longhand, which he folded into his wallet, accepting responsibility in the event of Overlord’s failure.

The note said: "Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air, and the navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone."

That night Eisenhower drove to Newbury, where the 101st Airborne Division was preparing to fly out. He walked among the paratroopers, with their blackened faces, and spoke to as many of them as he could. Then he waited until the last of them were in the air before returning to headquarters around midnight, his mind filled with thoughts of the brave men who would risk their lives at dawn.

On Thursday, as we commemorate the 75th Anniversary of D-Day, we know the story of what happened on the Normandy coast. The scenes of courage, of horror, of loss and ultimately triumph are stamped on our minds.

It was the beginning of the end for Hitler, and although VE Day would not occur until May 8, 1945, we know we have the brave forces who fought on D-Day to thank for our victory.

On the evening of June 6, as the early positive reports from the invasion reached his desk in the Oval Office, President Roosevelt, who had accepted the risk of the invasion back in Tehran, was filled with a mixture of relief and also heartache over the sacrifices suffered that day. He chose to broadcast to the nation — not a speech, but a prayer.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

President Roosevelt said this prayer to radio listeners: "Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity ... they will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph … Some will never return. Embrace these, Father, and receive them, Thy heroic servants, into Thy kingdom."

When President Trump delivers his D-Day remarks Thursday at the U.S. cemetery in Normandy, he has the rare opportunity to pay tribute with emotion, personal stories, and soaring words to the service and the sacrifice of those who died on those beaches and saved the world.