These days, people communicate their love to one another by exchanging texts, e-mails, or instant messages.

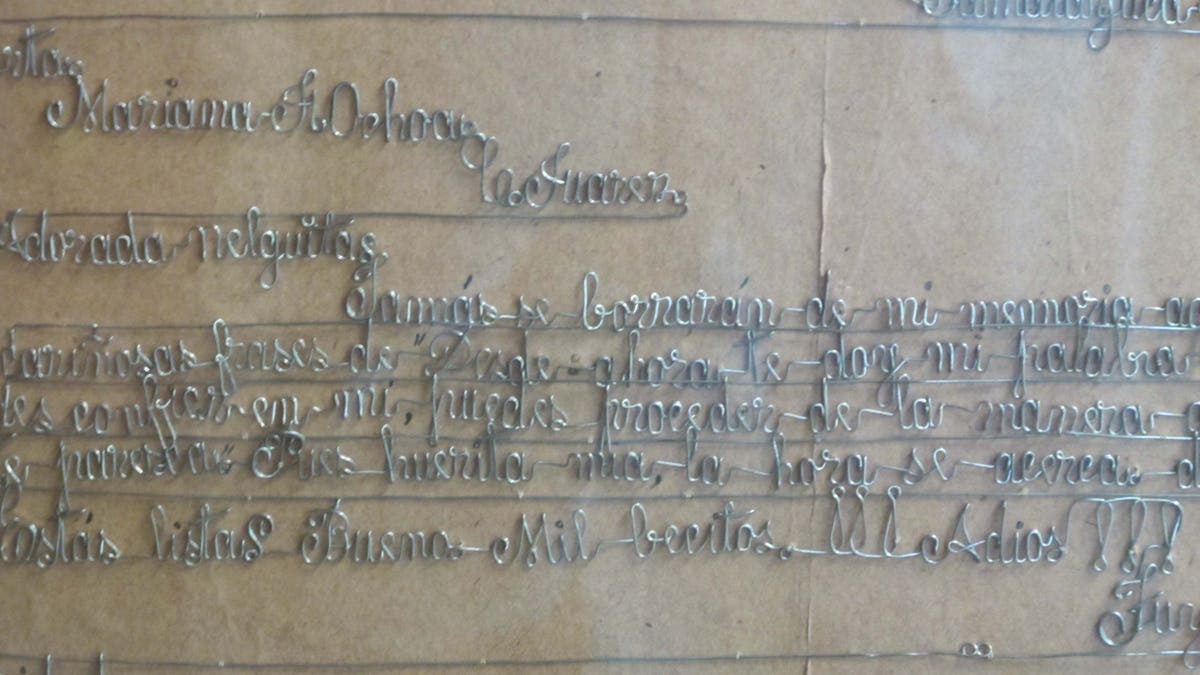

The El Paso Museum of History is hoping to inspire a more old-fashioned form of courtship: love letters. To that end, they've put on display an unusual family keepsake. On lend from Esperanza Lopez Almeida, 88, it is a 101-year-old love letter that her father wrote by twisting a thin wire into words. Written shortly before the start of the Mexican Revolution, it was his way of proposing marriage to her mother.

Because of their different backgrounds, Almeida said, her parents could not date. In fact, they could hardly speak to one another. Their relationship grew through passing letters. Almeida’s father, Jose Lopez, was born and raised in Samalayuca, Mexico, 30 miles south of Juarez. Her mother, Marana Ochoa Velarde, an American, grew up outside of El Paso. To ask for Velarde’s hand in marriage, Lopez used his profession as a telegrapher and crafted a letter using wire and wood.

They met because Velarde would frequently travel to Mexico with her grandfather, transporting crops.

“They just looked at each other far away,” said Almeida. There was some interest, and they started smiling at one another.

“One of those trips, he passed her a letter,” said Almeida.

That started up the correspondence.

“It was an everyday natural occurrence for them,” Patricia Almeida said about her grandparents.

Their romantic relationship continued only by letter, even up to the marriage proposal.

Lopez used some wire from his telegraph station to write: "Güerita mia, la hora se acerca, debes prepararte. Estás lista? Bueno. Mil besitos y Adios. Tuyo hasta la eternidad."

Translated: "My fair one, the time is coming and you should prepare. Are you ready? OK. A thousand kisses and Goodbye. Yours for all eternity."

Almeida says her mother didn’t respond right away. In fact, her father sent a follow up letter. They were able to get married after her father got the okay from her grandfather.

Six months into their marriage, the Mexican Revolution got underway. Velarde was three months pregnant with their first child.

According to Almeida, revolution leader Pancho Villa’s men kidnapped her father, worried he would send telegraphs warning of that they were coming to seize private property.

They left him in the desert.

“He survived by eating cactuses and drinking his own urine,” said Almeida.

Days later, he made it back to his wife. His shoes were torn and he had grown a scruffy beard. “He looked like a hobo,” said Almeida.

A hundred and one years later, the family has decided to share the letter and story with the El Paso Museum of History.

“This is precious,” said museum director Julia Bussinger. “I can’t believe this type of document exists. This is better than literature and poetry.”

Bussinger hopes the letter will encourage people to start writing letters more often.

“I challenge the rest of the world to create this type of document,” she said.

Mary Diaz de Leon says her grandfather’s letter teaches valuable family history to her children: “My daughters are in college. They can’t wait to come back and hear stories from their grandmother.”

For the next several months the letter will be on display as part of the El Paso Museum’s Mexican Revolution exhibit

Patrick Manning is an El Paso, TX-based Junior Reporter for Fox News.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino