Bacteria - including the MRSA superbug -may be more resistant to our most powerful antibiotics after a winter spurt of prescriptions, says a new study.

"Antibiotic use tends to go up in the winter months because they are inappropriately prescribed and that usually shows up a few months later in hospitals in the form of antibiotic resistance," said Dr. Ramanan Laxminarayan, who led the new study at Princeton University, New Jersey.

Widespread inappropriate use of antibiotics is driving the increase in resistance by encouraging the survival of bugs that can fight the drugs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"We're seeing an inability to treat patients who have resistant infections; they stay in hospital for longer, incur more hospitalization costs, and are more likely to die," said Laxminarayan.

For the new study, published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, Laxminarayan and his team looked at more than 1.5 billion prescriptions filled at U.S. pharmacies between 1999 and 2007. The prescriptions only accounted for antibiotic use outside hospitals.

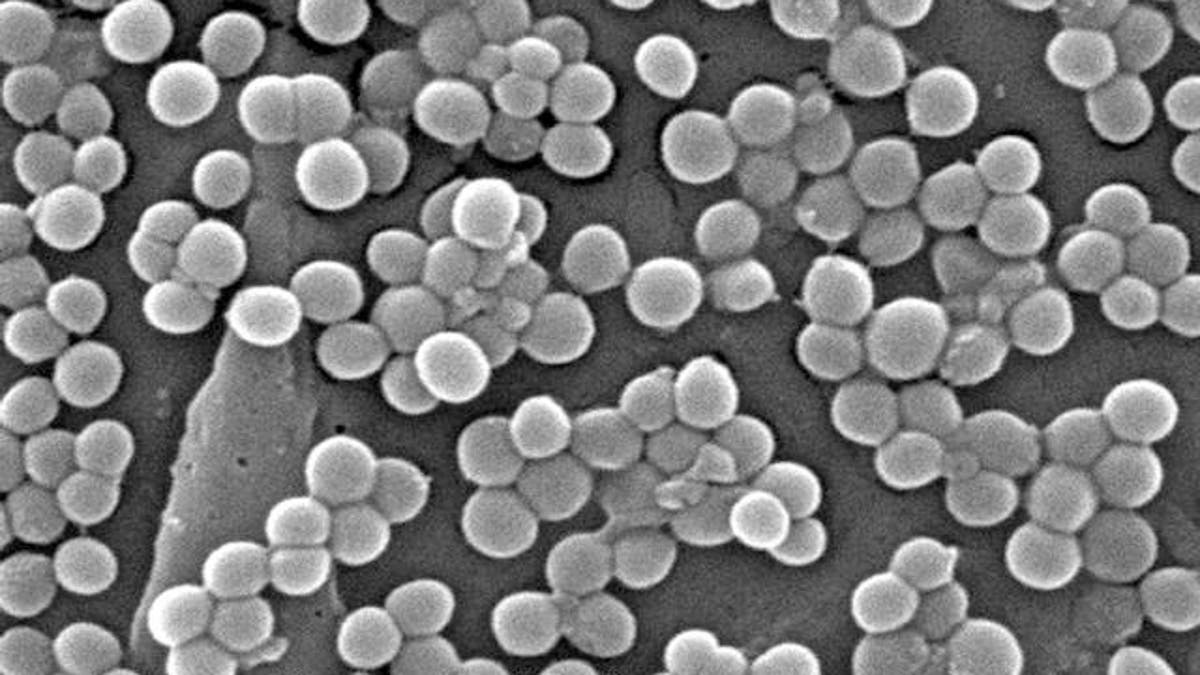

They also looked at the results of nearly 5 million tests for antibiotic resistance in E. coli and more than 2 million for MRSA - methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus - collected from 300 labs across the U.S.

When prescriptions for two commonly prescribed classes of antibiotics - penicillins such as ampicillin, which is used to treat ailments like ear infections, and fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin, commonly used to treat urinary tract infections - increased in winter, researchers saw an uptick in E. coli and MRSA resistance to those same antibiotics about a month later.

For example, when penicillin prescriptions increased from 3.3 million in July 2006 to 5.8 million in January 2007, the rate of E. coli resistant to ampicillin rose from 42 to 45 percent.

MRSA resistance to ciprofloxacin rose by 5 percent to 38 percent as prescriptions per month increased by almost a million between July 2006 and January 2007.

E. coli resistance to ciprofloxacin gradually increased from 2 percent to 17 percent between 1999 and 2007, with the difference between summer and winter also growing over time, Laxminarayan told Reuters Health in an email.

The right antibiotics

This sort of time-related data can add to evidence that antibiotic use causes bacterial resistance, said Dr. Alastair Hay, who has done research on antibiotic resistance at Bristol University in the UK.

However, it doesn't prove antibiotics are the only cause of bacterial resistance; for example, in the winter months resistant bacteria might be more easily passed from person to person, added Hay, who wasn't involved in the study.

And while the study did look at common bacteria, there are a lot of other bugs out there, said Dr. Betsy Foxman, who studies antibiotic resistance at the University of Michigan.

The study was also limited because researchers weren't able to account for antibiotic use in hospitals, which is also seasonal.

National campaigns to prevent bacterial resistance focus on making sure patients get the right antibiotics for the right amount of time.

"There's an idea that we can control resistance in hospitals with good stewardship programs, and we think those are important, but they are limited in importance by what's going on going outside of the hospital setting as well," said Laxminarayan.

According to the CDC, only 48 percent of hospitals currently have such a program in place.

"An important way to control resistance in hospitals is to ensure that people get a seasonal influenza vaccine, including health care workers, and that we really target our campaign against antibiotic use during the winter months," said Laxminarayan.

"Patients also need to ask themselves if they need an antibiotic," said Foxman.