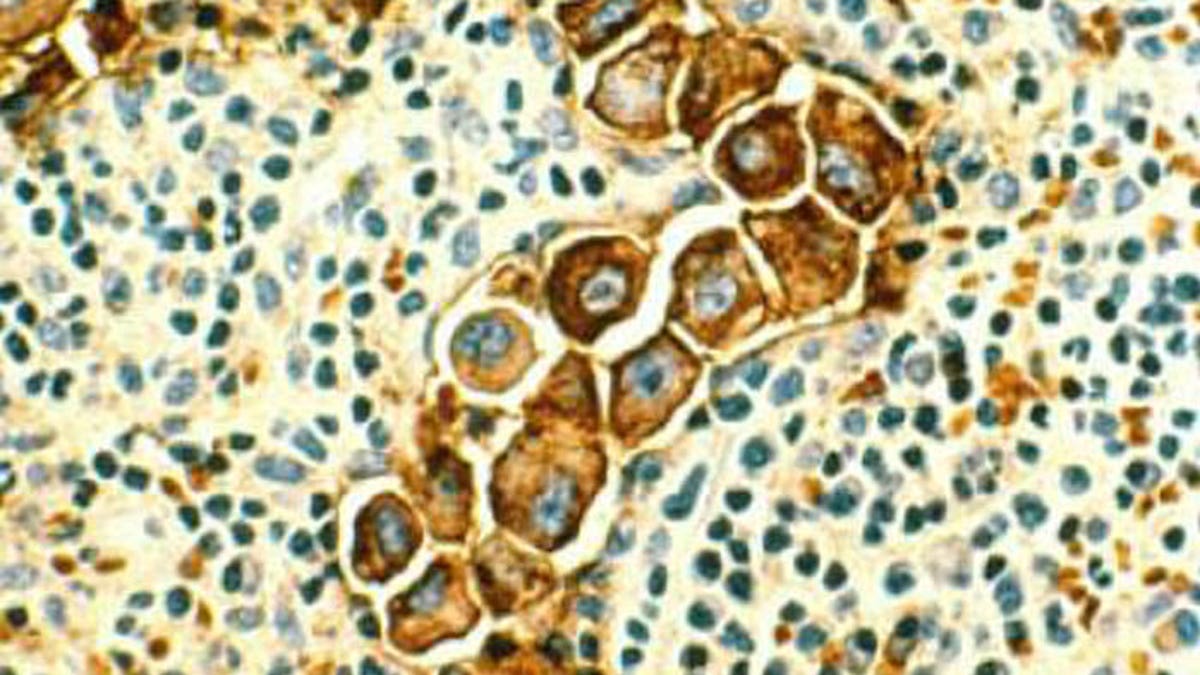

This image shows metastasized human breast cancer cells (magnified 400 times, stained brown) in lymph nodes. (National Cancer Institute)

If you’re keeping up with the Kardashians, you may already know that they got the BRCA gene test on last week’s episode. The reality show matriarch, Kris, thought it would be a good idea since they have a family history of breast cancer. But Khloe, 31, took some convincing. After watching her father succumb to esophageal cancer in 2003, she didn’t want to obsess over the possibility that she might suffer a similar fate: “If I’m going to get something, I’m going to get something,” she explained. “I’m not going to live my life in fear.”

Khloe’s concern is not uncommon—and the episode raised important awareness about the BRCA gene mutations. (Fortunately all four women received negative results.) However, the producers glossed over a few key details. We reached out to genetic experts to learn more about what you should keep in mind if you’re considering the test.

RELATED: 12 Things That Probably Don’t Increase Breast Cancer Risk

What exactly is the BRCA test?

It detects harmful variations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. (If one of your parents carries a mutation, there is a 50 percent changes that you have it too.) A positive result means you are at risk of developing breast, ovarian, and other cancers. While there is no way to “rid your body” of a BRCA mutation, “knowledge is power,” says Susan Klugman, MD, director of Reproductive and Medical Genetics at Montefiore Health System and professor of Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. Knowing the mutation is there gives you options. You can work with your doctor to make sure you are getting the proper screenings (including MRIs, mammograms, and pelvic sonograms), she says. Prophylactic surgeries (to remove your breasts or ovaries) may also be an option.

RELATED: 15 Worst Things You Can Say to Someone Battling Breast Cancer

Who should get tested?

A family history of cancer isn’t the only factor to weigh, says Mary Freivogel, the president-elect of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). It isn’t that simple. The National Cancer Institute has developed a series of screening tools to help evaluate whether a woman may have inherited a mutation. For example, if one of your relatives had both breast and ovarian cancer--or breast cancer that was diagnosed before she turned 50—you would be a candidate for the test. If you’re concerned, Freivogel recommends making an appointment with a genetic counselor. All families are different and some signs may not be as obvious, she explains. “What [a counselor is] able to do is take a family history and figure out if this is a pattern that concerns something hereditary, or if it is a pattern that’s probably explained by something else.” (You can use the NSGC’s online directory to find a counselor in your area.)

RELATED: 25 Breast Cancer Myths Busted

What if I just don’t want to know?

Like Khloe, many women worry that a positive test result will feel like a death sentence, and create unwanted anxiety about the future. Freivogel suggests that you should think about whether a positive result would change what you are currently doing to protect your health. “If I had a patient that said, ‘I’ve already had my ovaries removed for some other reason, I would not consider a preventative mastectomy, even if I had a BRCA mutation, and my family history puts me at enough risk that I’m already getting screened very carefully, I’m getting mammograms.’ Would that person do anything differently if she got a BRCA result? Maybe not.”

But if there are preventative steps that you’re not already taking, knowing your BRCA status could literally save your life. And if you’re thinking about getting pregnant in the future, the test could potentially help protect your baby too. Dr. Klugman explains that a procedure (called Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis) performed during an IVF cycle can help doctors identify the embryos that don’t carry the treacherous mutation.

Like Freivogel, Dr. Klugman also recommends talking to a health care provider—like a genetic counselor or an oncologist—to help you understand the pros and risks of analyzing your DNA. But ultimately, she points out, “any genetic testing is up to the patient.”