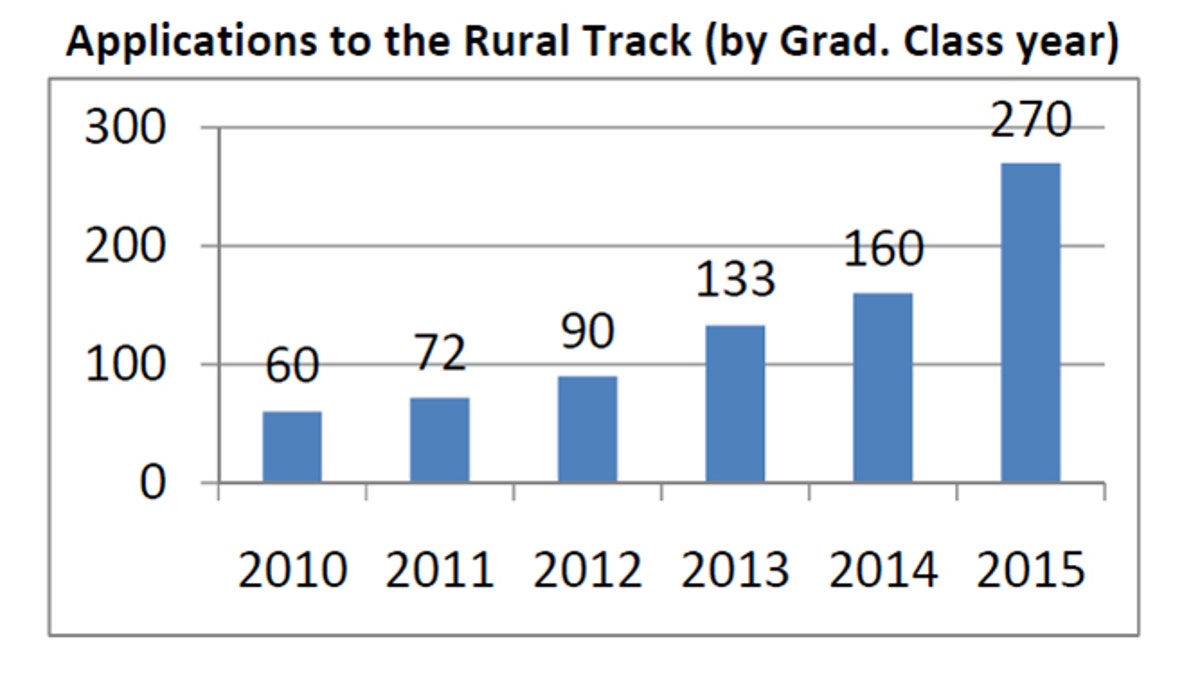

Student applying to the University of Colorado Medical School's rural track program has soared, according to this chart which shows applicants based on their projected graduation year. (Dr. Mark Deutchman)

Growing up, Hollie Vigil looked on helplessly as diabetes, obesity and hypertension ran rampant in her extended Latino family. When she decided to become a doctor, she vowed she would help this demographic once she got her degree.

To fulfill her mission, Vigil could easily stay in Denver where she is going to medical school. Twenty percent of the city is Latino. But the 24-year-old wants to go where doctors are truly needed in the state: small rural towns.

She has her sights set on Manzanola, a hamlet of 500 people, about 30 percent of who are Hispanic, in southeastern Colorado about 40 miles from where she grew up.

“Rural areas are a very good place to raise a family,” she says. “There’s a close-knit community and lots of outdoor things to do like hunting and fishing. Also, as a doctor, I’m attracted to the continuity of care and the closeness I’ll be able to form with my patients.”

Vigil’s plans are exactly what staff at the University of Colorado School of Medicine had in mind when they formed their rural track program six years ago as a solution to the growing scarcity of rural doctors, a problem that’s mirrored around the country. Nationwide, 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, but only 9 percent of doctors practice there.

“There’s a significant part of our state that is short of primary care providers and we’re trying to fix that,” says Mark Deutchman, who directs Colorado’s rural track program. He said about 10 percent of U.S. medical schools have similar programs.

“Historically,” he says, “we’ve done pretty well in admitting students who have a rural background, but what we never had before was a system that would nurture their interest once they were in medical school. “

To keep the students’ interest alive, the faculty host workshops for rural track students to teach them specific medical skills they’ll need to practice in rural areas. Most rural doctors are general practitioners so it’s not unusual for them to know everything from basic obstetrics to geriatrics.

“We call it womb to tomb,” said Deutchman.

The faculty also address non-medical issues such as the social adjustment necessary to practicing in rural settings.

“They’re going to run across their patients in non-medical settings at church, the library, the local park,” Deutchman says. “When they go into the grocery store, they’re going to be buying groceries from their patients. They’re going to feel more responsibility for the health and well-being of their patients because they’re also their neighbors.”

Perhaps the most important part of the program are the internships, which students do multiple times several months at a time during the four-year program in a variety of rural settings around the state.

This past summer, for instance, University of Colorado rural track students went to the San Luis Valley in the southern part of the state. An area that is 47 percent Hispanic and where the number of doctors fluctuates like a roller coaster ride, according to Freddie Jaquez, executive director of the San Luis Valley Area Health Education Center. “Sometimes, we have enough,” he says. “Sometimes, we don’t.”

Aaron Abeyta, who grew up in the San Luis Valley and returned after going away to college, said most doctors who come to the valley don’t stay long. Indeed, many new doctors go to rural areas and serve a few years because the government will forgive their medical school loans.

“We feel like this is a pit stop for them on the way to something bigger and better,” he said. “I don’t know that anyone feels used per se, but ultimately everyone feels like we’re a ready-bunch of guinea pigs for them.”

The 40-year-old who teaches English at Adams State College was asked to speak to University of Colorado medical students when they visited over the summer.

“I told them if you’re going to come and be in this community then be in this community,” he said, “even if it’s only for a year. If you take care of the community and show you really care, they’ll reciprocate.”

Perhaps the best way to get a doctor to stay long term is to start with the youth in the area. Jaquez’s nonprofit sponsors a program called “Grow Your Own,” which is designed to nurture local high school students contemplating health care careers through mentorship and educational opportunities.

“There’s research that says you have a better chance of having health care professionals in rural communities if they’re from your community in the first place,” he said “We bank on that concept.”

Still, he says, the majority of them may not come back.

“We play the odds game. I tell them every chance I get ... You may like it in the city and that’s where you’ll practice, but at some point remember where you came from and come back home.”

Nancy Averett is a freelance writer based in Ohio.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino