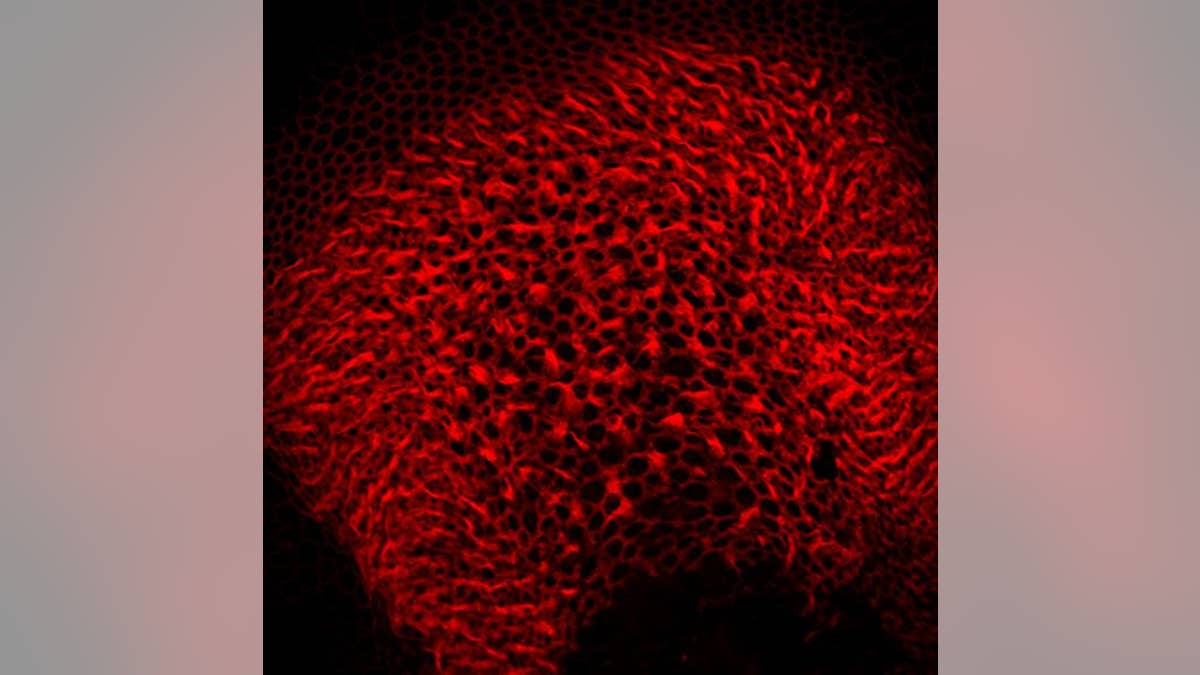

To super-charge a specific virus as a gene carrier into the inner ear, the team used a form of the virus wrapped in protective bubbles called exosomes (tiny bubbles made of cell membrane). Those cells naturally bud off exosomes that carry the virus inside them. (Harvard Medical School)

In a small study on deaf mice, researchers at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital used a novel gene-delivery technique to help the animals make gains in hearing and balance, but cautioned that the therapy is years away from use in humans.

Working with mice born without a gene critical for hair cell function, researchers injected a modified adeno-associated virus (AAV) with the missing gene into the inner ears of mouse pups shortly after birth. One month after treatment, nine of 12 mice had some level of hearing restored and could be startled by a loud clap, a standard behavioral test for hearing. Four of the mice could hear sounds roughly the equivalent of a conversation in a loud restaurant, 70 to 80 decibels.

Mice with damaged or missing hair cells show balance abnormalities and the mice treated in this study showed notably improved balance compared to their untreated counterparts.

Previous gene-delivery techniques have been unable to reach crucial hair cells, the delicate sensors in the inner ear that capture sound and head movement and convert them to neural signals for hearing and balance.

The new model reached a subset of hair cells that had been largely impenetrable by using AAV. Scientists grew regular AAV virus inside cells, which then budded off tiny bubbles made of cell membrane that carry the AAV virus inside them. This membrane virus is coated with proteins that bind to cell receptors, which may be why the bubble-wrapped version of AAV binds more easily to surfaces of hair cells and penetrates them more efficiently, scientists said in a news release.

"Unlike current approaches in the field, we didn't change or directly modify the virus. Instead, we gave it a vehicle to travel in, making it better capable of navigating the terrain inside the inner ear and accessing previously resistant cells," co-senior author and co-investigator Casey Maguire, Harvard Medical School assistant professor of neurology at the Mass General, said in a news release.

Their approach will not be ready for use in humans anytime soon, but gene therapy carries the promise of restoring hearing in people with several forms of both genetic and acquired deafness, the team said in a news release. Every year, about one in 1,000 babies are born with a hearing impairment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.