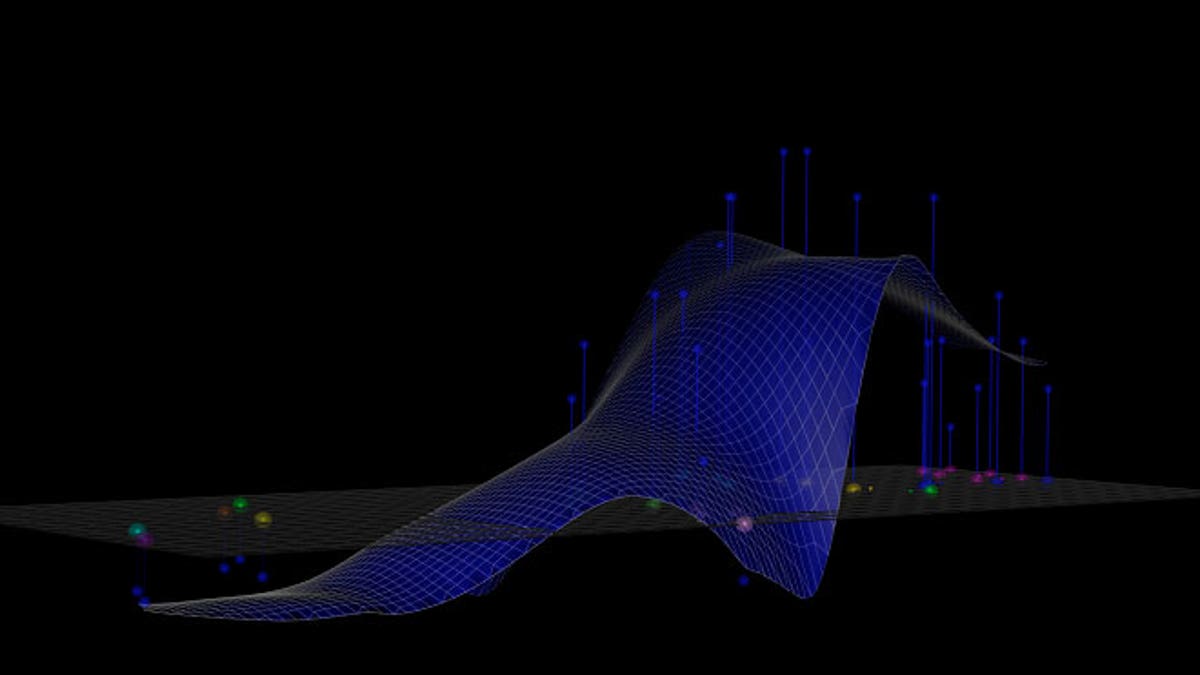

A computer image shows a distinct antibody landscape, which illustrates an individual's profile of immunity to different strains of influenza. (Photo courtesy of the Center for Pathogen Evolution, University of Cambridge)

Developing a seasonal flu vaccine has long challenged scientists, as predicting the strain that will impact the public in any given year involves an educated guessing game. The flu, like the Ebola virus, is comprised of RNA, not DNA, genes. These viruses’ distinct genetic makeup enables them to mutate and evolve efficiently— sometimes long after a vaccination has been developed and distributed, leaving even the vaccinated public vulnerable to infection.

But U.K. researchers have discovered a potential solution to this problem: considering an individual’s antibody response to develop a stronger flu vaccine.

“What we found was that our immune system response is much more broad than anybody ever thought— that when we get the flu vaccine today, we also get a lot of immune memory to the previous strains of flu,” study author Derek Smith, professor of infectious disease informatics at Cambridge University, told FoxNews.com. “We actually only need the antibodies that protect against the strains circulating now.”

Influenza is a nasty virus. During the 1918 flu pandemic, an estimated 50 million people— many of them healthy adults— died. Today, seasonal influenza continues to plague the global population. Every year, the virus infects about 10 percent of people worldwide, and about half a million individuals die at its hands. Young children and the elderly with underlying health conditions are especially at risk.

To develop a seasonal flu vaccine today, thousands of health professionals in over 100 countries take throat swabs of people who exhibit flu-like symptoms. This network of medical workers, organized by the World Health Organization (WHO), sends samples to national influenza laboratories where they are tested to see whether they are the flu. Any sample that tests positive for the flu is sent to various international WHO labs for examination. The five major labs are in Atlanta, London, Melbourne, Tokyo and Beijing.

Every February, the WHO’s Influenza Vaccine Composition Committee decides which strain— selected from those that are already circulating— will go into the following year’s seasonal flu vaccine. Scientists base that choice on which strain they believe is most likely to affect the global population. Afterward, manufacturers create 350 million doses of the final vaccine to distribute across the world.

“During that period— from when we decide what strain to put in the vaccine until this coming winter, that’s about a year— sometimes the virus will have evolved during that year,” Smith said. “And when it does that, the flu vaccine is not as good as when it doesn’t evolve. And so that’s a problem sometimes.”

Smith and his colleagues write in their paper, published in the Nov. 20 issue of the journal Science, that closer study of the body’s immunological memory— a phenomenon they call the “back boost”— may help scientists pre-empt future strains of the seasonal flu.

“If we could manage to get an early warning or prediction of what strains of flu were going to circulate in the future, then we could put that strain in the vaccine,” Smith said. “If we did that, of course if the flu did evolve during that year to those new strains, that would be a great vaccine, but the crucial thing is— and the important thing is— even if it doesn’t evolve, because of the back boost, that vaccine would still protect against the current viruses.”

Scientists have known about individuals’ unique antibody landscapes for about 15 years, Smith said. His team’s future research, which has so far been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), will involve studying the flu’s evolution. A clinical trial, which Smith said he hopes to begin within a year or two, will follow.

Smith pointed out that just because scientists are working to develop a stronger approach to protect against the flu doesn’t mean the current vaccine isn’t worth getting.

“Everybody who is at risk for the flu should be getting that vaccine,” he said. “It’s really important.”

But, he said, “the possibility to create vaccines that look into the future is really a reality because they are just as good if not a little better than the current vaccines— even if the virus doesn’t evolve. It’s like we get a free guess to be ahead of the game.”