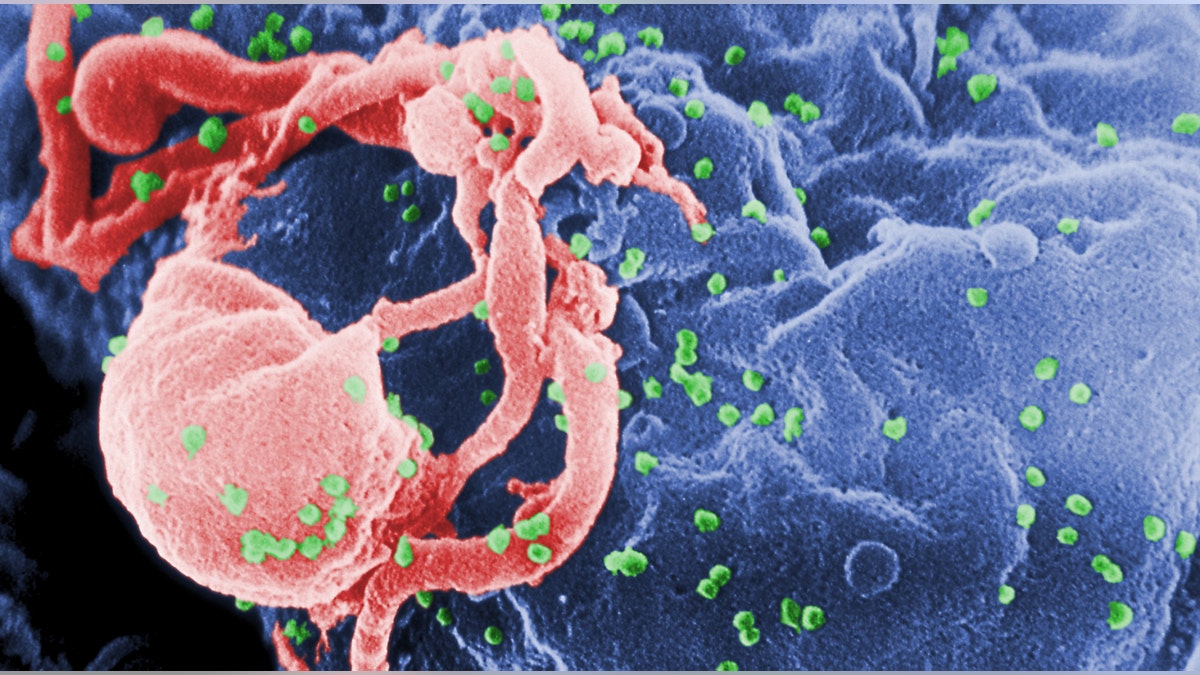

Scanning electron micrograph of HIV-1 budding from cultured lymphocyte. The multiple round bumps on cell surface represent sites of assembly and budding of virions. (CDC.gov)

A new matchstick-size implant that dispenses antiretroviral drugs may aid in HIV prevention, early-stage findings published last week in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy suggest.

Studies show strict adherence to antiretroviral drugs is imperative to suppress HIV and reduce the risk of drug resistance. But following a drug regimen can be difficult when most patients take about three different drugs daily, said study author Marc Baum, president and founder of the Oak Crest Institute of Science, whose team designed the implantable device that dispenses the antiretroviral medication.

The risk of contracting HIV is even higher in vulnerable populations, including in sub-Saharan Africa, where in some countries, life expectancies for patients has fallen below 40 years, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). While the number and type of drugs for HIV patients and HIV-vulnerable populations vary, adherence is a universal problem.

“We wanted to take adherence out of the equation,” Baum, who received his Ph.D. in organic chemistry from London’s Imperial College, told FoxNews.com. The Oak Crest Institute of Science is a nonprofit specializing in environmental and biomedical chemistry research and education.

The device Baum’s team designed is similar to the contraceptive implant. It measures about 40 millimeters long and 2 millimeters in diameter, and can be inserted into the upper arm. The subdermal implant is made of a PVA-coated silicone cylinder, which is approved by the the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

To test the safety of the device with a new HIV medication, study authors surgically implanted the device in four healthy dogs and collected plasma samples over a 40-day period. They analyzed their blood and measured the drug, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), in the animals’ immune cells to analyze its potency. Gilead Sciences Inc. is testing TAF for FDA approval and announced phase 3 results in February. It filed a New Drug Application with the FDA in November 2014, according to the biopharmaceutical company’s website.

Baum’s study evaluated the device’s ability to release TAF over time. Study authors chose dogs rather than mice or rats to stay consistent with Gilead’s preclinical work of TAF, which involved dogs. Plus, researchers needed to collect at least 3 milliliters of blood to measure drug content in subjects’ immune cells and rodents aren’t large enough to draw that amount of plasma.

Study authors observed that the medication sustained release through the device, and successfully treated the healthy dogs at a potency rate about 30 times the concentration that would be needed to prevent HIV infection in a healthy person.

“In the end, we were delighted to see that this can work and that we can scale back on how much drug we’re delivering, which of course will make the implant last longer,” Baum said. “Once we redesign the implant, we’re shooting for an implant that will last six months or even a year.”

Baum said his team’s findings are the first to prove sustained-release nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)— drugs that block viral DNA production, a first-line defense against the virus— may be a viable option for HIV prevention. He noted that previous challenges to introducing a long-acting form of HIV drugs via an implantable device included finding the proper medication.

“You’re very limited with the range of drugs that are amenable to this technology,” he said. “They have to be potent, have a long half-life in the body and be very soluble.”

Baum noted that although the device needs to be redesigned to sustain release of a smaller amount of the drug for human use and future clinical trials, based on his team’s preliminary findings, sustained release of the drug didn’t appear to have adverse side effects on the dogs in the study.

“A lot of side effects from the same drug go away when you do sustained release because you’re maintaining therapeutically active levels without delivering an enormous amount of drug,” Baum said.

According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, common side effects to currently available HIV medication include nausea and vomiting, anemia, diarrhea, dizziness, fatigue, pain and nerve problems, and rash.

Baum said his team is currently waiting for funding to conduct a mice study, which they are aiming to begin in 2015. Within the next four or five years, after fine-tuning the implant design, they would file an application with the FDA to begin clinical trials.

“Over 7,000 people a day are contracting HIV … mostly in sub-Saharan Africa,” Baum said. “If we can make a dent in that with our technology, it would make an enormous impact.”