(Bunyos)

Researchers in the United Kingdom have found that lung cancer can remain hidden up to 20 years before it is detectable, suggesting evidence for why the disease is the deadliest form of cancer worldwide.

“The problem with lung cancer is we often diagnose patients too late,” said study author Charles Swanton, a professor of cancer research at the London Research Institute.

In the study, published in the journal Science, researchers found that after an initial genetic fault— often due to smoking— lung cancer genes mutate and adapt, causing different parts of a single tumor to become genetically unique.

Scientists studied lung cancers from seven patients, including smokers, ex-smokers and never-smokers, and examined how their tumors evolved.

Two of the seven study participants gave up smoking 20 years before the study began. Swanton’s team noted that in these patients, smoking left a scar in the genome of mutations which allowed them to time the genetic events during the course of the cancers’ evolution.

Between these two individuals, many of the mutations were linked to smoking. But as the disease progressed, another enzyme, APOBEC, began causing more mutations than smoking. “Why that is we don’t know,” Swanton said. “We wonder if smoking itself is advancing it.”

APOBEC’s main function is to mutate viruses, but in the study cancer cells appeared to hijack the enzyme, said study author Nick McGranahan, a biometrician in Swanton’s lab.

The gamut of faults found within the lung cancers could explain why targeted treatments have limited success.

Swanton said the findings are consistent with the process of natural selection. “The more diverse a tumor, the more high-risk it’s likely to be,” he said.

Over 40,000 people are diagnosed with lung cancer each year, and the disease has less than a 10 percent survival rate at least five years after diagnosis. According to the World Health Organization, the cancer kills 4,300 people a day.

Two-thirds of lung cancer patients are diagnosed with advanced forms of the disease— a time when treatments are less likely to be effective.

“If we can somehow detect these tumors earlier, we might be able to target these mutations in a very early stage and maybe, hopefully be in a state where patients are curable,” said study author Elza De Bruin, a scientist in Swanton’s lab.

Because these findings suggest a long latency period for lung cancer, future research could explore whether circulating tumor DNA from blood would help with early detection.

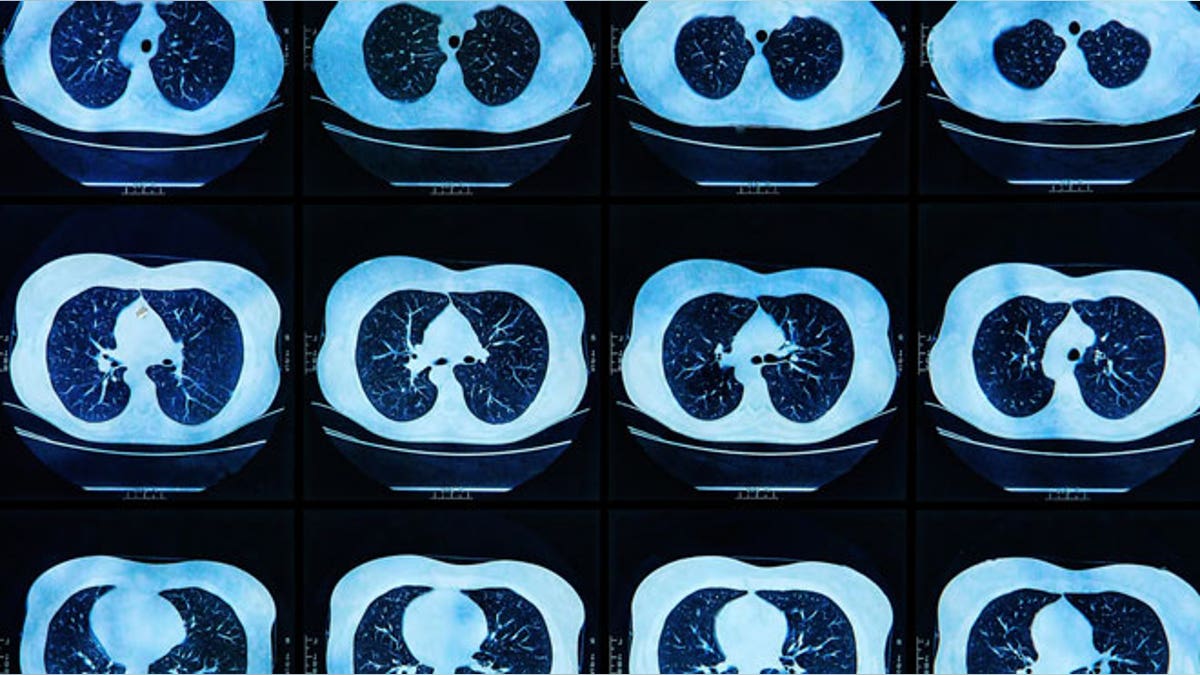

“That would be before the tumors even appeared on a CT scan,” Swanton said. “It would allow us to understand or define a group of high-risk people for screening.”