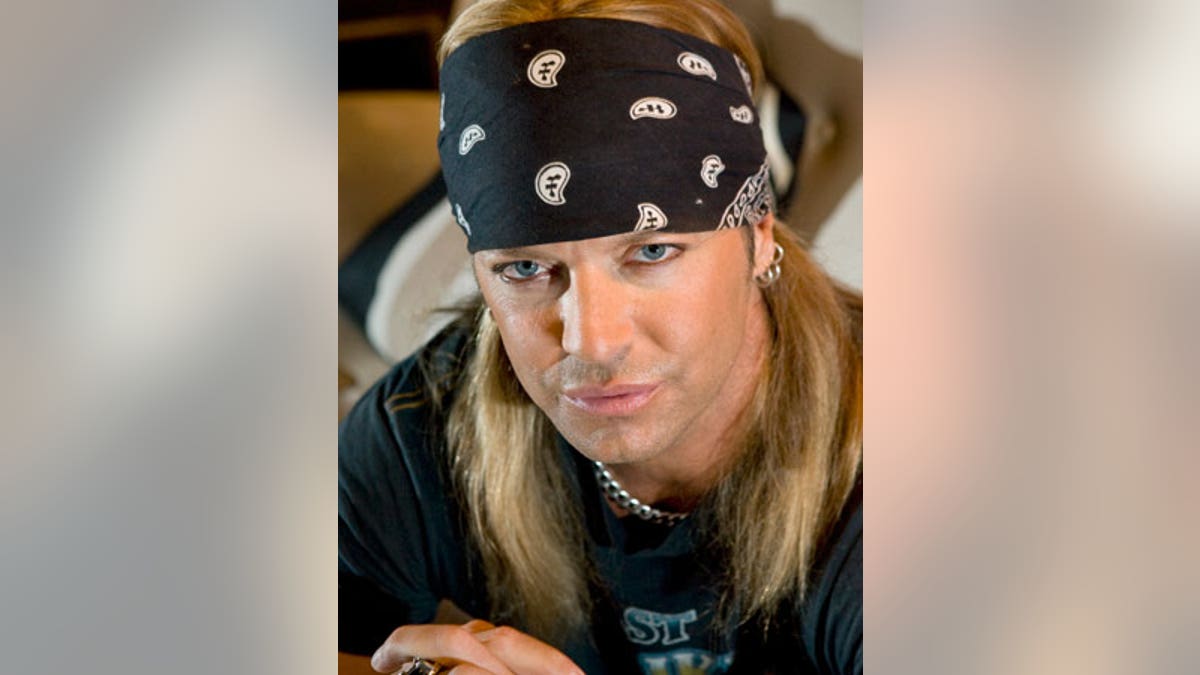

Musician and reality star Bret Michaels’ has had more than his fair share of hospital visits — his lifetime battle with diabetes, his appendectomy in April, and his brain hemorrhage on April 21, which left him fighting for his life in the intensive care unit for days.

According to an update from Michaels’ website, tests included an MRI and CT scan. He also "received a doppler ultrasound of his legs and lower abdomen looking for blood clots and most importantly an ultrasound bubble test of his heart was conducted which proved positive for patent foramen ovale (PFO), a hole in the heart."

So why wasn’t the hole in his heart caught before now?

Dr. Nieca Goldberg, a cardiologist at New York University Cardiac & Vascular Institute in Manhattan, who has not treated Michaels, told FoxNews.com that a PFO is not something that cardiologists just come across; it is something that needs to be specifically tested for.

“Generally when young people have strokes is when we (cardiologists) look for those things,” she said.

After feeling numbness on his left side Thursday night, Michaels. 47, went to the hospital as a precaution. After some testing, doctors concluded that the numbness he felt was actually a symptom of a transient ischemic attack, or a warning stroke.

Common procedure for someone in Michaels’ situation is to undergo a transoesophageal echocardiogram, where an ultrasound probe is inserted down the patient’s throat in order to look directly behind the heart and examine the chambers.

Michaels has unknowingly had a hole in his heart since he was born.

“We see this in children, but the hole in the heart is supposed to close up before they come out of the womb. But it is common for adults where the hole has never closed up. It is congenital,” Goldberg said.

This health scare comes just a day after Michaels appeared on “Oprah Winfrey Show,” where he told Oprah he was making a speedy recovery from his brain hemorrhage.

“His brain hemorrhage is not exactly related, it’s always hard to know unless you know their medical history,” she said. “It is hard to connect the brain hemorrhage to the stroke, but it is possible.”

Michaels is undergoing care at St. Joseph's Hospital's Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz., where doctors said his condition is "operable and treatable."

“Usually blood thinners are a common treatment, which makes the situation more complicated. There are risks and benefits, so he and his doctor will determine if the benefits outweigh the risk,” Goldberg said.

There are also surgical options for Michaels.

“There are procedures that can close the hole in the heart, or he could have a clamshell surgery,” she said.

Clamshells are sealing devices that cover the hole in the hopes that the heart will mend itself.

“There are a lot of options, but he will have to be monitored closely. Patients with a PFO are at a higher risk of stroke.” Goldberg said.